The performance by Objective Spectacle is a medley of eclectic parts, almost a sonic brainstorm. Boisterous, “sports crowd” cheering morphs into what sounds like the merciless pelting of a rainstorm, then incrementally decelerates, dilating into what could be the last few drops of the storm. The audience is drawn into a game of suspense, ambivalent expectations, collective dynamics, manipulation and suggestion in a constant loop of different clapping textures. Each clapper holds their body differently: some react spastically when they clap, others draw themselves tightly inwards. Some clap perfunctorily, out of duty; some seem to feel they have clapped enough and look like they are done clapping. The clappers become a micro-polity or temporary constituency, influencing each other’s reactions, from primordial, frenzied, cult-like clap to the reserved, obligatory clap; from the mindless “groupthink” of affirmation culture to the exhaustion of collective patterns of euphoria.

From the 1830s when professional clappers—“claqueurs”—were hired by Paris theatre and opera houses to encourage a positive reaction from the audience, applause has been the prima facie ritual of how a spectator receives a performance. What happens when audience reaction—how an audience receives a performance—is elevated to the rank of the performance itself?

Weaving Together a Patchwork Quilt of Different Clapping Textures

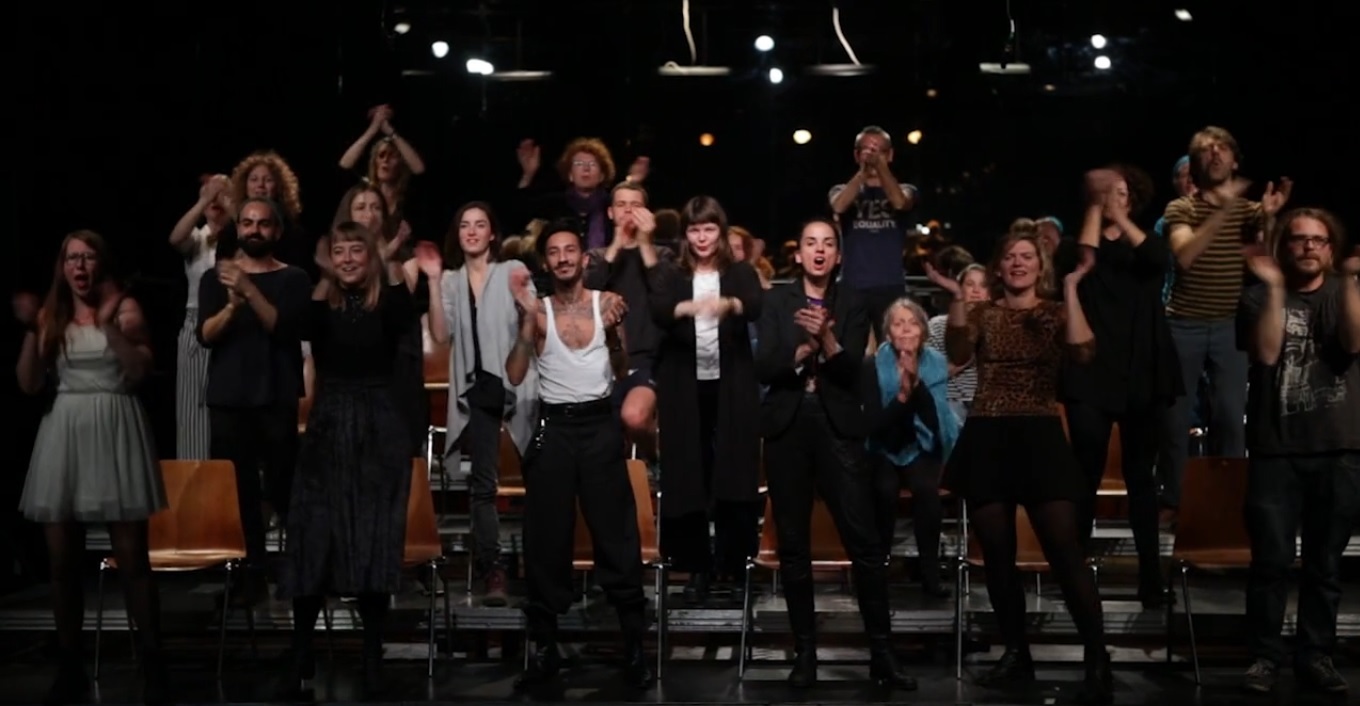

At the beginning of CLAP the 24 performers stroll in at the same time as the real audience are seating themselves. They take their places in four rows of bleacher seats with the same off-hand insouciance as the audience. The narrator stands off to the side and queries the audience in a preternaturally calm voice, “I want to ask you to remember the first time you clapped. It’s not easy. Or you could even think of the last time you clapped. That’s easier. We could even try to remind ourselves of the sensation of when you are about to clap. When you are just raising your hand. You are asking yourself if you are allowed to break the silence […] Maybe there is a tension in the air. You can try to remember the sensation of air on the skin, on the finger.”

The lights go out, the narration dissolves and is replaced by a single clap, reminiscent of the portentous tick-tock of a giant clock. The theatre is pitch black, and the performers soon erupt in a boisterous clapping spree, complete with occasional cries of “yahoo” and “bravo.” The clapping and cheering continue for another four minutes in pitch darkness, the volume gradually decreasing. Eventually, the clapping turns into a mélange of disparate sighs, whistles, murmurings, occasional whispers and what can only be described as a cross between what a human might sound like if they were imitating a frenetic puppy breathing heavily and what a human might sound like if they were trying to repress their laughter, but unable to prevent deformed, barely recognizable giggles from escaping in sporadic bursts.

After six minutes of darkness the lights return, and the 24 performers begin clapping again, several of them with their eyes closed. The clapping gradually slows down until the performers are completely silent and still, looking directly at the audience, with the faint sound of what seems to be a ticker-tape running in the background. After about a minute has passed in silence, one man starts to clap. Someone else joins him slowly, followed by two more, then three, five, and soon the whole group is clapping again robustly. This round of clapping dwindles over a few minutes, as the clappers drop out one after another, until we are back with absolute silence and stillness. At this point the performers appear to become intent on a comedy program or performance, as they stare straight ahead and burst out laughing. Some almost fall off their chairs from laughter, others slap the back of the person sitting next to them to share the hilarity of the moment, and one man has stand up as his laughter becomes uncontrollable.

In the next episode, as if in a déjà vu or a dream on an endless loop, a lone performer starts to clap slowly and warily. The clap accelerates, goes double-time, and a minute later all the performers erupt in clapping and cheering again. For the first time, all 24 performers have popped out of their chairs to clap and cheer. Different people hold themselves differently. One woman with a long dark braid is stiff and restrained, clapping in a reserved, almost begrudging way. Another woman in a crinoline mini-skirt is much more energetic, bobbing up and down and shifting from left to right foot as she claps, like a boxer getting ready for a fight. A man performs the heteronormative “dude” clap, holding his body straight upright. Another man bobs his head back and forth horizontally when he claps, as if listening to music on (imaginary) headphones. Two women jump up and down in mirthful unison as they clap, like human versions of popping popcorn. Of all the clapping sets thus far, this is the most unreserved, accompanied by the sound of feet stomping monstrously on the bleachers, creating a sense of pandemonium. Then the lights go out and the theatre is once again pitch dark (we are about halfway through the performance).

At this point, the narrator returns, spotlighted in the darkness, and says in his faux-soothing voice, “There are so many reasons to clap. Like the rising of the sun in the countryside. Birth, newborns. Important people, superstars like Michael Jackson /Jordan, Trump, Hillary, Barack. But normal people too.” Then he lists the first names of the 24 clappers, who clap each other as they step up one by one into the spotlight. The red hue of the light and a metallic industrial sound in the background lend an eerie feel to this part of the piece, almost like the midnight indoctrination ceremony of a cult. The clapping soon synchronizes into “clapping to a beat” as a pulsating disco beat emerges in the background.

Finally the narrator asks (with the exaggerated gusto of a game-show host), “Are you ready?” He counts down from 10 to zero. At zero the lights go out, and there are nine minutes of clapping in pitch darkness. About two minutes in, the clapping gradually morphs into what sounds like people playing patty cake or perhaps even horse’s hooves on the ground, mixed with what sounds like the light pitter-patter of falling rain.

Still in total darkness, we now hear the boom of fireworks. The clapping begins again, but it is more orchestrated than anything we have heard yet. It comes in triplets or 4/4 time, like morse code or sonic/rhythmic hieroglyphics trying to impart some esoteric message. As an audience member, I felt it was my duty to find a pattern in the clapping, as if it could not be random. The clapping gathered itself together: a few people clapped, then several others joined in and the clap accelerated, then it suddenly stopped and the sequence began again. The effect reminded me of several people sprinting very fast in spurts, then suddenly stopping for a few seconds, waiting for the others to catch up and then starting off again. This was accompanied by background sounds: the occasional stray note played on a cello and an inexplicable sound like the bellowing of a dying cow. After some minutes of fitful stops and starts, the clapping seemed to find itself and decide where it wanted to go, as if obeying some unspoken collective agreement. It consolidated resolutely into a single unison clap, which began slowly and then accelerated. The sound of fireworks grew louder and more intense at the same time. The theatre remained pitch black except for six small backlights, in which the faint outlines of people could be discerned. The 24 performers were now down off the bleacher seats, on the stage, clapping frenetically in the semi-dark, jumping in unison from right to left and left to right as if possessed by a force beyond their control. The scene was reminiscent of mystics or Sufi “twirlers” who spin for hours, oblivious to what is around them or how their movements might be interpreted by an observer.

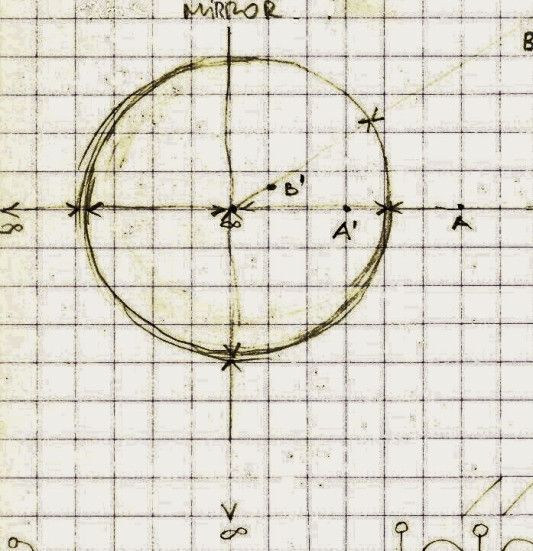

Doppelgängers, Mirrors, and Empty Museums

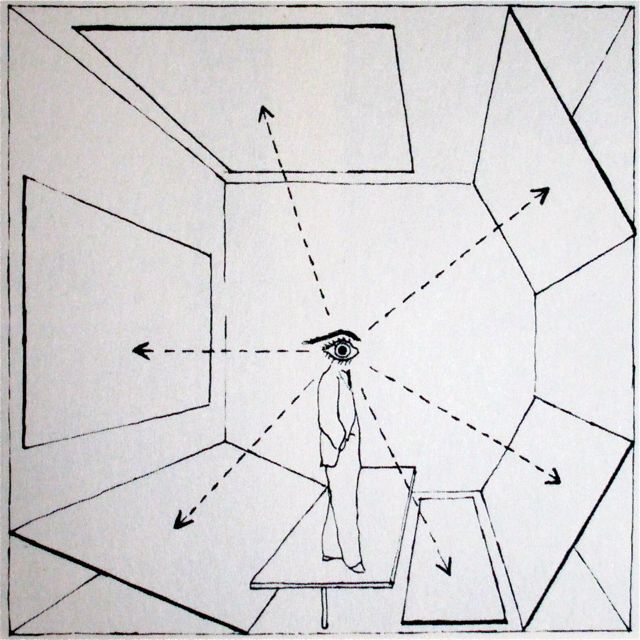

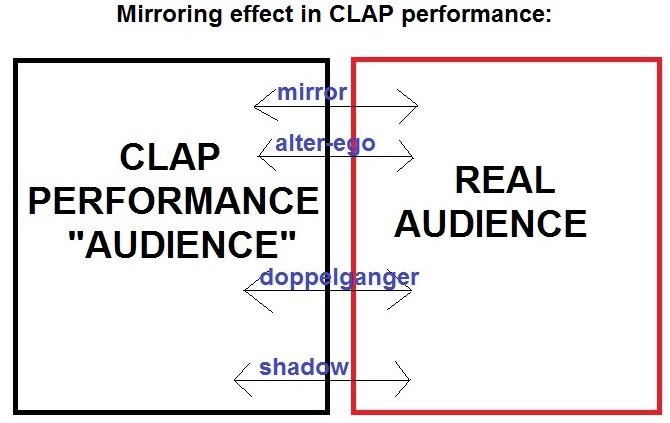

For me the piece evoked comparisons with Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s The Empty Museum—a museum exhibition that consisted of an empty room, putting on display the container or bare physical structure that houses art. Similarly, instead of giving us the conventional content of a theatre performance—dialogue, narrative development, character development, actors, plot, set design—CLAP laid bare the structural convention that defines the performance itself: applause. The audience becomes a doppelgänger or mirror image of the clappers on stage, reminiscent of the double-presence in Foucault’s description of the mirror as a heterotopia in Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias: “Between these two, I would then set that sort of mixed experience which partakes of the qualities of both types of location, the mirror. It is, after all, a utopia, in that it is a place without a place. In it, I see myself where I am not, in an unreal space that opens up potentially beyond its surface; there I am down there where I am not, a sort of shadow that makes my appearance visible to myself, allowing me to look at myself where I do not exist: utopia of the mirror. At the same time, we are dealing with a heterotopia. The mirror really exists and has a kind of comeback effect on the place that I occupy: starting from it, in fact, I find myself absent from the place where I am, in that I see myself in there I am over there, there where I am not, a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent.” [1]

This “comeback effect” Foucault refers to of seeing oneself in a place where one is absent, and which he ascribes to the heterotopia-as-mirror, materializes in CLAP. The real audience and the 24 performers arrive and sit down at the same time, followed by a moment of silence when the two audience bodies— “real” and performative—sit in silence staring at each other. This gave me a feeling of discomfort, which I could not explain at the time. As I realized afterwards, I felt uncomfortable because the performers on the stage were not looking at us in the blank way that stage performers are trained to look at the audience, looking “through” us. Instead, they were looking at us as actual people—as if they recognized us—and there was something vaguely or unexpectedly confrontational about this. It was as if we in the “real” audience unexpectedly lost our anonymity. I was not sure how I should feel: should I be pleased/displeased or relieved/annoyed/threatened, or simply neutral, about this loss of my anonymity as audience member?

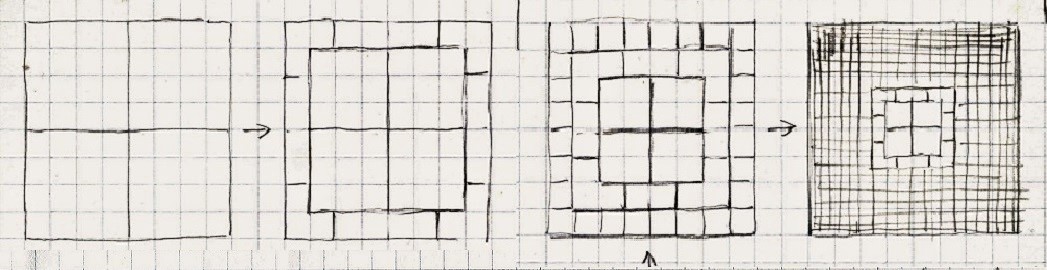

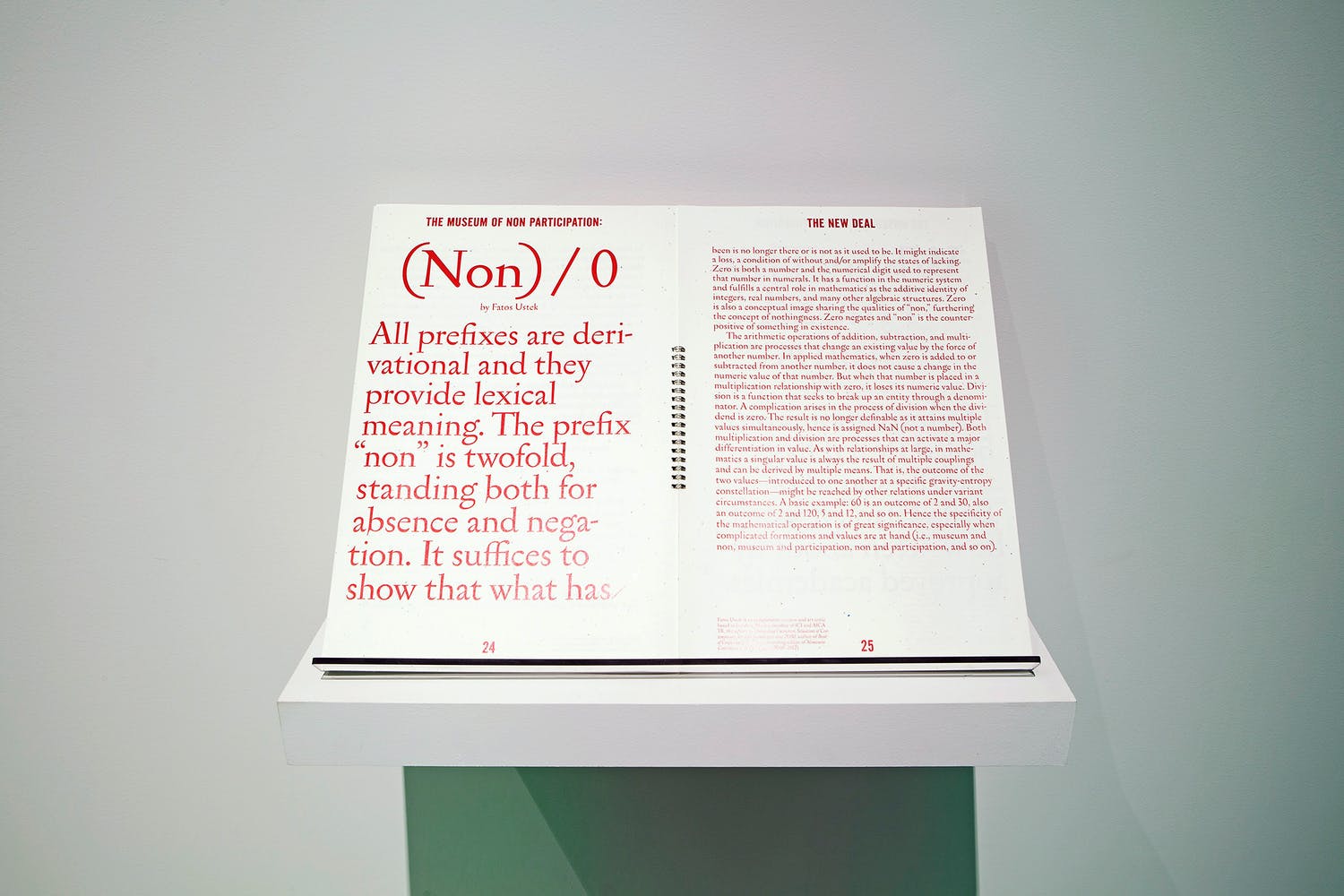

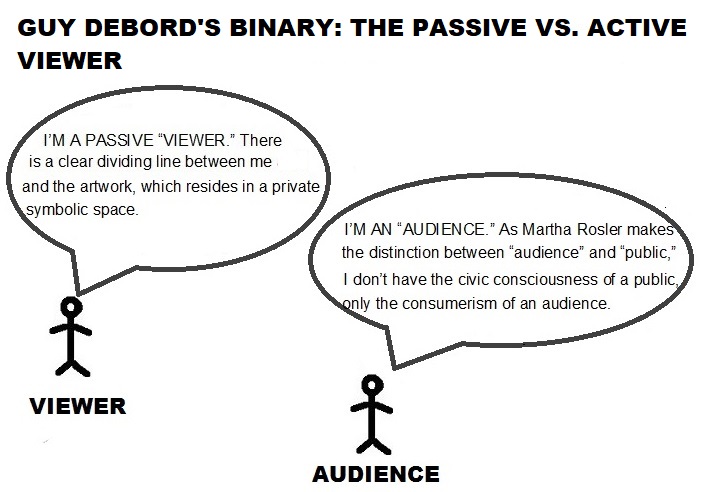

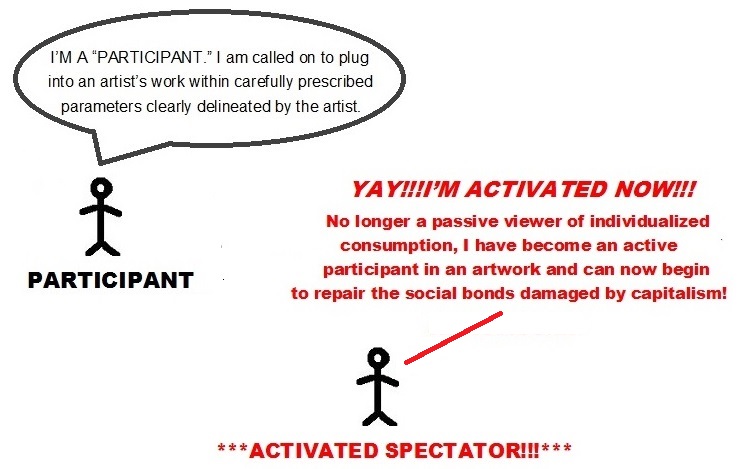

A question that comes immediately to mind, given the tacit and oblique role of the audience in CLAP, is whether or not this performance was a form of “participatory art”? Participatory art forms require the participation of the audience in order to be “activated” as artwork. The rhetoric of active vs. passive spectator is crucial to the ideology of participatory art. Descended from Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, which excoriated our society’s subservience to the “spectacle” (“The spectacle is capital accumulated to the point where it becomes image”), the rhetoric of the “active viewer” is imbued with emancipatory aspirations that militate against an atomized society supposedly numbed by individual consumption. [2] Debord’s almost Manichean dichotomy between the “active” and “passive” spectator is marked by a tacit heroism on the part of the “active spectator” who is able to escape alienation and false consciousness, and to gain autonomy.

However, theories of interpassivity and the interpassive spectator (proposed by Robert Pfaller and Slavoj Zizek) have exploded Debord’s binarism of “active viewer=good,” “passive viewer=bad”. Interpassive spectatorship is neither passive nor active, but instead denotes situations in which we give away our passivity, in which our passive experience can be delegated, transferred or performed through another. Examples include the Greek chorus, which performs our innermost thoughts, professional mourners hired to do the weeping at a funeral, and the fetish, where we transfer power or agency to an object that serves as a proxy for our desires or wishes. Whereas Debord’s “passive-viewer subject” was mesmerized by spectacle while his “active-viewer subject” was able to launch interventions into the corrupted “society of the spectacle,” interpassivity is a critical negation of the project of subjectivization as such. Interpassivity is a form of spectatorship that creates a proxy or outside agent to experience something in your place—whether that proxy be an object, person, activity, etc. Transference, displacement, proxy, split subjectivities and fetish are central to the theory of interpassive spectatorship. Robert Pfaller’s theory of interpassivity complicates, negates, and renders obsolete the Debordian rhetoric of “active vs. passive” spectatorship that has dominated much participatory and socially engaged (visual) art since 1968.

Pfaller’s theory of interpassivity queers Debord’s over-simplistic rhetoric of the active vs. passive viewer. Debord’s active/passive viewer theory has the orthodoxy of “straightness” (heterosexuality), premised as it is on an over-determined, schematic “good cop/bad cop” binary division between active and passive viewer, analogous to heteronormativity as an epistemological regime predicated on a Manichean dichotomy (man vs. woman) with no subtlety, gradation or overlap between opposing polarities. Pfaller’s theory is queer in that it complicates, blurs or renders obsolete over-simplistic binary divisions and schematic categorizations. The Debordian rhetoric of active/passive viewer is also straight in another way, because it is what everybody takes for granted as the prevailing ideology; it is the entrenched regime currently in power. The notion that an “active viewer” is superior to a “passive viewer” (descended from Debord) is the taken-for-granted assumption embedded in (if not fueling) innumerable subsequent waves of art movements, from the Situationists to Fluxus to relational aesthetics to “social practice” (socially engaged art) to the whole basis of the Whitney ISP (a highly influential Marxist para-academic program in New York City for visual artists/ theorists that has churned out luminaries who comprise the canon of conceptual art and institutional critique of the last 50 years of (largely American) art history, including Jenny Holzer, Andrea Fraser, Mark Dion, Glenn Ligon, Grant Kester, Gregg Bordowitz, Felix Gonzales-Torres, Sharon Hayes, Emily Jacir, Miwon Kwon, Maria Lind, Helen Molesworth, and countless others). [3] This assumption that an “active viewer” is superior to a “passive viewer” is deeply entrenched in a particular corner of the art world. Meanwhile, interpassivity is the marginalized underdog (as a theory, its influence is not as widespread). Another way in which interpassivity is “queer’ is that a gay person understands split subjectivity in way a heterosexual person never can. A heterosexual person cannot imagine what it is like to have a conflict between one’s public image and one’s private persona in the way a gay person can. The entire notion of divided subjectivity—a subjectivity paradoxically split against itself–is something that resonates, represents even, a queer subjectivity in a way that it cannot do for a heterosexual.

I bring up the question of whether CLAP qualifies as participatory art because of the way the piece ended. The piece concluded with each of the 24 clappers taking a bow one-by-one, and then standing on stage clapping together with the real audience. I asked the creator of the piece if he considered the ending—when the real audience and the performers clap together—to be a part of the piece, and he replied in the affirmative. Once could say that the piece ends in an orgy of communal clapping and in this sense the piece verges on having a participatory element. Furthermore, in a subtle way the audience unwittingly participates in the piece simply by sitting where it is sitting: it provides a mirror image in which the 24 clappers on stage are reflected.

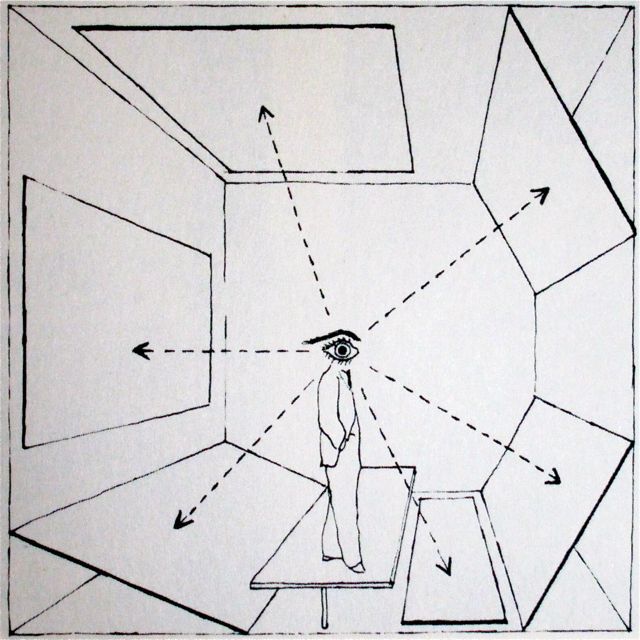

Insofar as CLAP had a participatory element, it was clearly not fueled by, nor informed by the prescriptive Debordian rhetoric of active vs. passive viewer. It was not governed by binary divisions or moralizing criteria for hierarchies where one type of viewer is superior to another (as the Debordian rhetoric presumes). The participatory element in CLAP can be better explained by the theory of interpassivity. The performers on stage seemingly usurp the role of the audience by taking on the audience’s task of clapping. By clapping for one hour, it as if the performers obviate the need for the real audience to clap, since that responsibility has been delegated to the clappers on stage. It is interesting to note that CLAP is reliant on the conventions of the stage in order to subvert these conventions. For example, if the exact same performance was put in a white cube gallery, it would lose its pungency. In a white cube gallery, viewers can come and go as they please, they do not have to stay from the beginning to the end of the performance and they can speak to each other during the performance. Also, in an art gallery, viewers are not seated in a pre-arranged format as they are in a theater. In CLAP the “real” audience is governed by the conventions of theater: they must sit in pre-arranged rows of seats, they must all sit facing the stage, they are generally expected to stay from the beginning until the end of the performance, they must be quiet. Without these conventions, CLAP would have nothing off of which to form a mirror image. It is because we in the audience are doing the exact same thing as the performers on stage—that is, sitting in rows of seats staring quietly straight ahead of us, and eventually clapping—that is where the piece gets its power. Without this, CLAP would not be able to create its uncanny mirroring effect, whereby the audience is confronted with the stark simplicity of looking at its exact double on stage. If we come to a performance with a certain mental architecture—we are prepared to sit in our chairs a certain way, to observe quietly what is happening on stage, to applaud as a response to the performance—to have this concatenation of unspoken rituals thrown back at us for us to simply observe on stage causes cognitive dissonance. If the people on stage are now doing what we as spectators usually do, what role is then left for us?

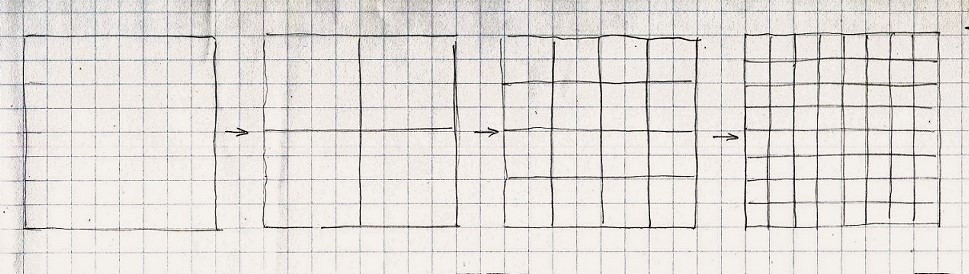

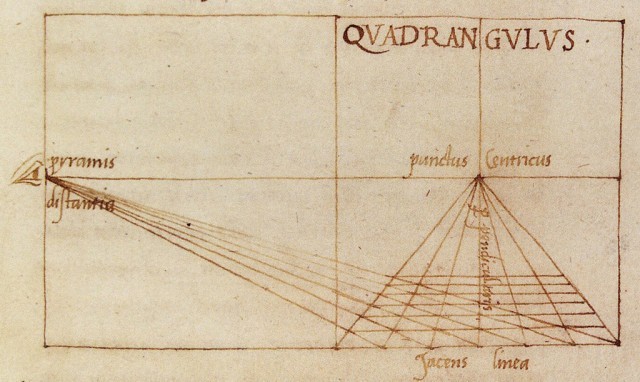

In his 1917 essay “Art as Device” the Russian and Soviet literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky expounded the concept of ostraneniye or “defamiliarization” (literally “making strange”)—a literary device that aimed to slow down and problematize the reader’s perception. [4] By subjecting the reader’s mind to a state of radical un-preparedness, ostraneniye jolts him or her out of the well-trodden paths of habitual perception, rendering something commonplace and ordinary suddenly unfamiliar. Shklovsky begins by describing how, over time, perception devolves into a rote habit, devoid of vitality or verve: “Considering the laws of perception, we see that routine actions become automatic. All our skills retreat into the unconscious-automatic domain; you will agree with this if you remember the feeling you had when holding a quill in your hand for the first time or speaking a foreign language for the first time and compare it to the feeling you have when doing it for the ten thousandth time.” [5]

Shklovsky calls this phenomenon “automatization” and states that the objective of art is to make objects unfamiliar again by the device of ostraneniye (“making strange” or, in the English translation we use, “enstrangement”): “Automatization eats things, clothes, furniture, your wife, and the fear of war. “If the whole complex life of many people is lived unconsciously, it is as if this life had never been.” And so this thing we call art exists in order to restore the sensation of life, in order to make us feel things, in order to make a stone stony. The goal of art is to create the sensation of seeing, and not merely recognizing, things; the device of art is the “enstrangement” of things and the complication of the form, which increases the duration and complexity of perception, as the process of perception is, in art, an end in itself and must be prolonged. Art is the means to live through the making of a thing; what has been made does not matter in art…” [6]

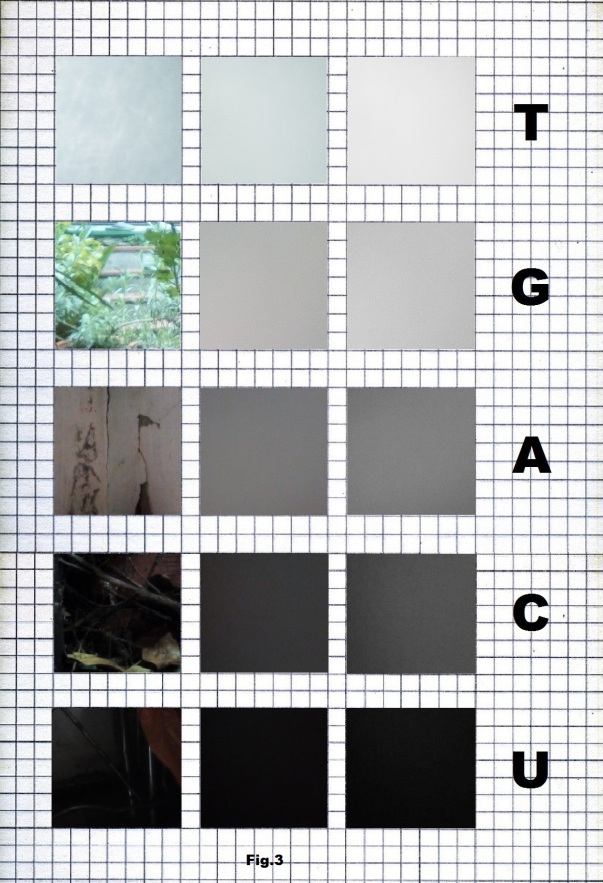

In this passage, Shklovsky bifurcates into a two-tiered epistemology: the realm of “seeing” vs. the realm of “recognizing.” For Shklovsky, these are mutually exclusive categories. We see Shklovsky refer to “recognizing” in terms that are almost pejorative, as a state of being so desensitized that one is “unconscious” to the point where it as if we had never even lived our own lives. One might deduce that Shklovsky sees the realm of “recognizing” as almost tantamount to a type of false consciousness that has to be punctured or woken up by “seeing.” Ostraneniye (“enstrangement”) is the name Shklovsky gives to a technique, by which we “make forms difficult” and “increase the difficulty and length of perception”: “And now, having elucidated the essence of this device, let us try to delineate the limits of its use. I personally believe that enstrangement is present almost wherever there is an image … The image is not a constant subject with changing predicates. The goal of an image is not to bring its meaning nearer to our understanding but to create a special way of experiencing an object, to make one not “recognize” but “see” it.” [7]

For Shklovsky, the purpose of enstrangement is to disrupt automatized perception: “When studying poetic language—be it phonetically or lexically, syntactically or semantically—we always encounter the same characteristic of art: it is created with the explicit purpose of deautomatizing perception. Vision is the artist’s goal; the artistic [object] is “artificially” created in such a way that perception lingers and reaches its greatest strength and length.” [8]

We can understand CLAP as a giant enstrangement (defamiliarization) project. By weaving us in and out and in and out of a giant patchwork-quilt tapestry of different sets and typologies of clapping, CLAP functions like a mental obstacle course we have to “get through”—something like a training. It is not an easy piece to get through, and at times elicited comparisons in my mind with John Cage’s famous “4’33” (1952) where Cage sat at his piano for 4 minutes and 33 seconds in silence. Cage’s performance must have tested the audience’s patience and CLAP calls for a certain degree of forbearance from the audience. By repetitively subjecting us to this stark and simple act of people clapping on stage, it tries to jolt us out of automatic perception of something we have done so many times that we don’t perceive it anymore. Using Shklovsky’s terms: we “recognize” how to clap and when to clap, but we don’t “see” it. Following Shklovsky’s exhortation to render something commonplace and ordinary suddenly unfamiliar, the question is: did the performance CLAP make clapping suddenly unfamiliar? Here the answer is more subtle. While there is nothing unfamiliar about people sitting in rows and clapping, what is indeed unfamiliar is to make this the subject of a performance. So in an oblique way, the answer is yes.

I chose to write about CLAP because it transformed (i.e. subverted) my idea of what performance can be. Before seeing CLAP, if somebody had asked me, “Do you think it would be possible to make a compelling or captivating performance consisting of nothing more than people clapping on stage for an hour?” I would have said, “No, that sounds like a recipe for disaster! I cannot imagine that such a performance would be any good!” And yet, by ingeniously presenting the subtleties of different gradations and textures of clapping and bodily affects that go with clapping, a captivating performance was created that consisted of almost nothing but people clapping on stage for one hour. I was struck by the purity of the work: it brought in no extraneous elements, but stripped the performance down to the bare essentials of its concept.

In this sense, I found myself comparing CLAP with the renowned No Manifesto (1965) by Yvonne Rainer. A founding member of Judson Church (an avant-garde dance collective in Greenwich Village, New York City in the 60s), Rainer was a postmodern choreographer who rejected the overwrought angst and theatricality of the modern dance canon that directly preceded her (exemplified by Martha Graham), advocating instead that dance be stripped to its bare essentials and incorporate movements of the every day. She set out her credo in No Manifesto (1965):

“No to spectacle.

No to virtuosity.

No to transformations and magic and make-believe.

No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image.

No to the heroic.

No to the anti-heroic.

No to trash imagery.

No to involvement of performer or spectator.

No to style.

No to camp.

No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.

No to eccentricity.

No to moving or being moved.” [9]

While CLAP is not a dance performance, it elicits comparisons with No Manifesto because it also says, ““No to spectacle,” “No to virtuosity,” “No to transformations and magic and make-believe,” “No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image,” “No to the heroic,” “No to the anti-heroic,” “No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.” In her Manifesto, Rainier rejects all the usual trappings or means by which a performance can “seduce” its audience. In similar vein, CLAP did not attempt to show “virtuoso” skill, it did not pound us with spectacle, it did not try to make its clappers into “stars,” it did not launch into make-believe. In fact, at the very beginning of the performance the narrator breaks down the “fourth wall” with his direct address to the audience asking us to remember the first time we clapped. His prologue sets us up to apprehend that the performance will not be premised upon illusion, mimicry, or dramatic verisimilitude, by which actors try to convince an audience that fictional events happening on stage are “real.” Instead, we are to take what is happening on stage for its literal actuality (a person on stage clapping is not “an actor clapping in a fictional story on stage in a fictional narrative,” but is nothing more and nothing less than a “real person clapping on stage”). In this sense, we might construe CLAP as a “performative readymade” (a term coined by Objective Spectacle) in that, just as Duchamp’s readymades were supposed to be indistinguishable from everyday objects, the clapping in CLAP was indistinguishable from everyday people clapping, unembellished by extraneous performative theatricality.

My only misgivings about the performance concern the role of the narrator. At times he felt extraneous, almost as if he was in the wrong piece, his faux-soothing voice reminiscent of a yoga instructor or the contrived earnestness of the “sensitive boyfriend.” He seemed to be “telling us what to think”, providing a road map for the world of clapping, but the road map was contrived and unnecessary. His delivery suggested ironic awareness that what he was saying was pointless, which made me wonder still more about his role. The clapping performance itself told us much more about clapping (without a single word being uttered) than the narrator who was explicitly “telling” us what to think about clapping. I might go so far as to say that the existence of the narrator seemed at times disrespectful to the integrity of the piece. Like a fly buzzing around you that you keeping swatting and you wish would go away, each time he intervened I thought to myself, “I hope he finishes quickly so we can get back to the clapping.” It became apparent to me that this was not a piece about language, as the parts that used language (the narrator’s interventions) were the only parts that were in any way contrived. This was a piece about SOUND and SPACE and BODIES IN SPACE MAKING (non-linguistic) SOUND.

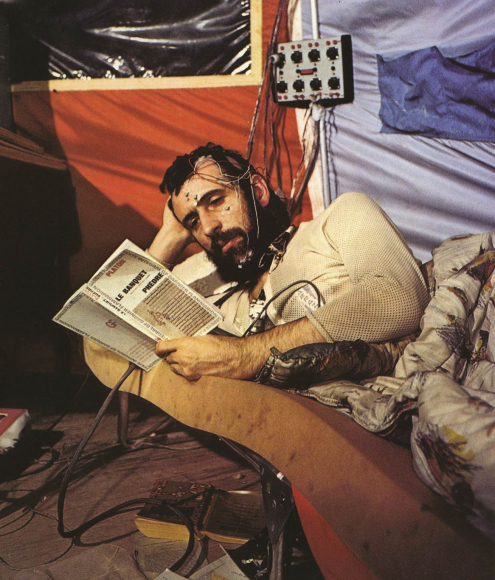

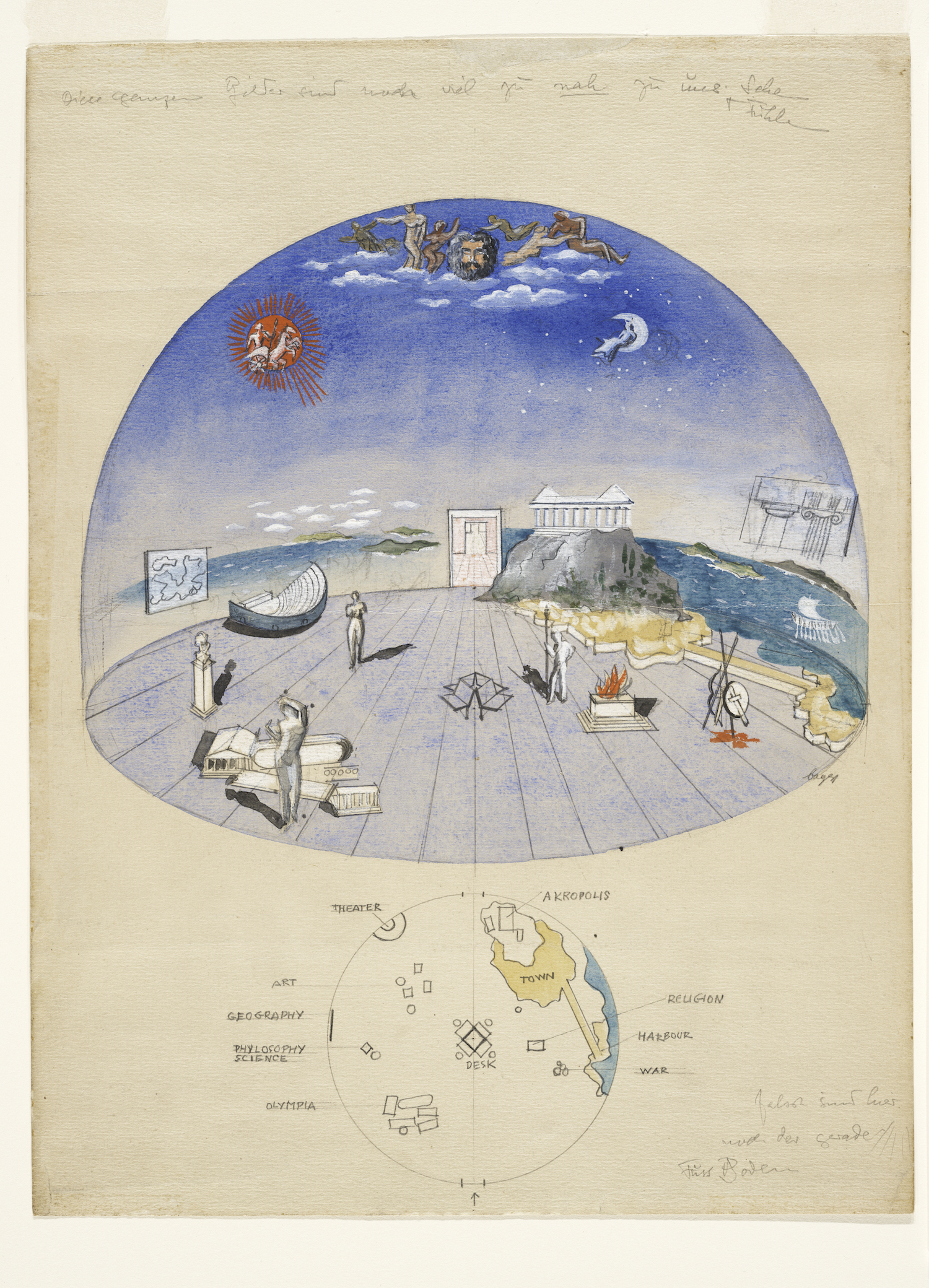

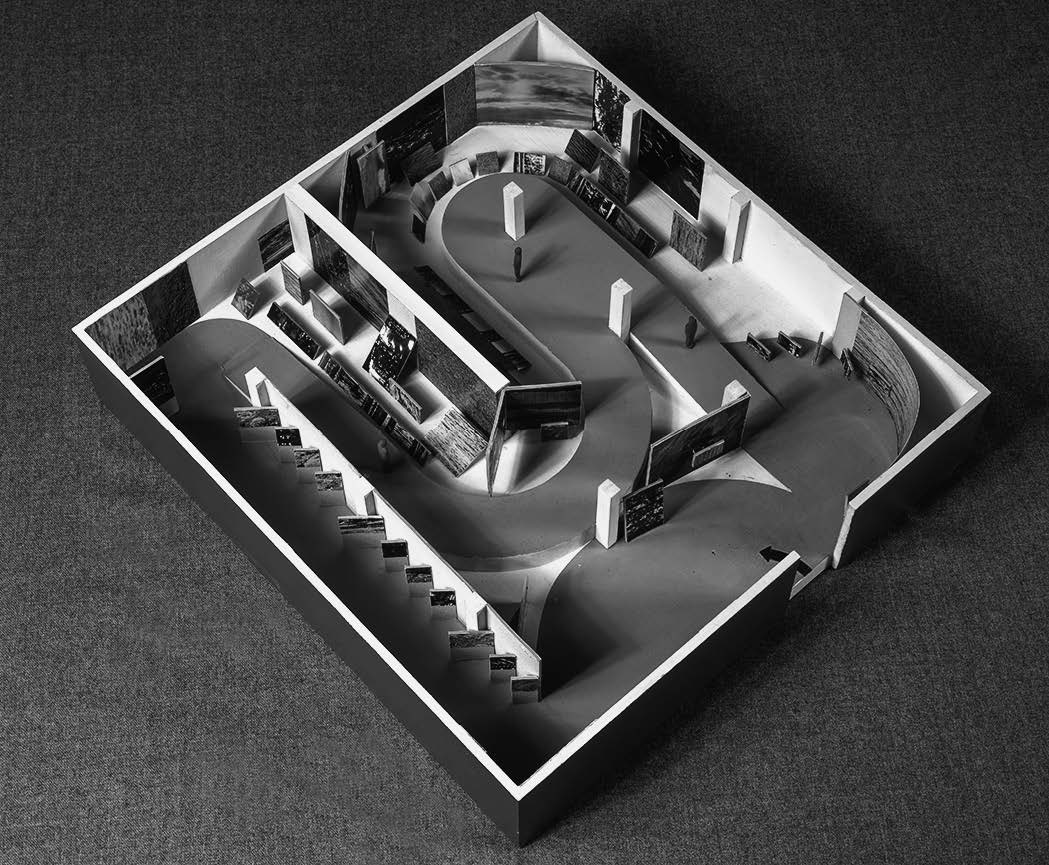

However, when this same piece was presented in a white-cube gallery context and reformulated as a “durational clap” installation/performance, the use of language took on a completely different coloring. For the durational CLAP performance (taken out of the black-box theater and re-formulated for the white-cube gallery) a sole performer sat in a chair laid with his back to the floor and mimed a clapping movement (without his hands actually touching) while a black and white film was played of various people clapping. This performance was like a conceptual “pedestrian scramble” (a crossroads with several intersections) where we were confronted with several elements simultaneously: the black and white moving image of people clapping, a real live person clapping, a sound score of people clapping and a sound score of a god-like omniscient voice uttering fragments of words (usually related to the history of clapping). In this performance, rather than formulating complete sentences (as in the theater performance), language was cut up into short phrases (some of them non-sequiturs) and spliced into the performance. This use of language was highly effective. Whereas in the black-box theater version of the piece the use of language seemed to work against its general thrust or principles, in the white-cube/gallery version, the use of language worked in concert with and enhanced it. Unlike in the theater/black-box version of the piece, in the white-cube gallery version language was not utilized for its literal meaning, but was hurled at the viewer like sonic readymades, contributing to an almost mystical (or other-worldly), trance-like atmosphere around the durational clapping. The sole real clapper (Christoph Wirth) in the durational performance of CLAP had an intensity, drive, and singleness of purpose in his clapping that was almost intimidating, and quite different from the occasionally jocular or light-hearted tenor of the clapping in the theater performance.

Again, I was struck by the purity of the CLAP durational performance in the gallery. In this age of buzzing, whirring, obnoxiously over-produced “multi-channel sound and video installations,” “movement sensors,” fetishistic infatuation with gadgets and gratuitous-use-of-technology-with-no-idea-behind-the-art (a malady afflicting the U.S. far more than Europe), I felt sheer relief that someone had the audacity still to believe that something as simple and unadorned as a person sitting in a chair clapping was worthy of a performance. The gallery performance confronted us with the stark economy of a single act repeated over and over in a way we haven’t really seen (at least not in this style) since the golden age of durational performance/conceptual art in the 1970s (Vito Acconci, Chris Burden, Bruce Nauman, etc.). (Furthermore, I would like to point out how delightfully unusual it is that a performance would have two separate versions—one version made for the black box theater and another version made for the white cube gallery space. To date, I can’t think of another piece or another artist who has done this).

CLAP was performed by Objective Spectacle at Berliner Festspiele, Ballhaus Ost (Berlin), Les Urbaines Festival (Lausanne, Switzerland), Théâtre en Mai Festival (Dijon, France), Carreau du Temple (Paris), Treibstoff Basel Festival, Théâtre les Halles (Sierre, Switzerland), Ringlokschuppen (Ruhr, Germany), PACT Zollverein (Essen, Germany), Theater Wrede, Teater Nordkraft (Aalborg, Denmark), Festival New Communities – Nordic Performing Art Days (Aalborg, Denmark) and it won the Premio Award for Theater and Dance in Switzerland.

Objective Spectacle consists of Christoph Wirth, Clementine Pohl, Bryan Eubanks, and many others. Berlin-based German artist Christoph Wirth’s work with Objective Spectacle often lies at the intersection between happening, performance, installation art and sound art, examining dispositives of spectacular sensation in medial settings, political environments, and figurations of society. Christoph is artistic director of Objective Spectacle and currently a fellow at Akademie for Theatre and Digitality in Dortmund, Germany. He was kind enough to answer my questions about the piece:

Andrea Liu: You mentioned something intriguing in a past conversation—the notion of clapping as a form of archiving. Can you elaborate on that?

Christoph Wirth/Objective Spectacle: Clapping is a form of archiving in the sense that it is a gesture where you are continually rewriting over the same, over the same, over the same (action). But the gesture itself is a materialization of or a result of an immaterial process in the sense that, when you clap, you clap in relation to what you saw in a performance, and what you saw in the performance is related to what you projected in your mind onto the performance. Clapping is materialist in that it is acoustic, it involves skin, bodily movements; but it is immaterial in that clapping is an act of remembering the intensity of what you just experienced. So in a weird way clapping is a materialist form of remembering the performance, but the remembering is an immaterial process.

Andrea: Something else you mentioned in a past conversation is that clapping is monstrous. Can you elaborate on that?

Christoph: In this piece I was interested in clapping as some sort of noise. I notice with clapping that speech gets eradicated, and applause can become monstrous, it can become super-alienating, almost like drone music or trance. When you go through this duration of an action and through repeating it, it turns into a durational mode and it’s this gesture because it’s totally inscribed into a habit. At a certain point, the space of experience becomes liminal, then the gesture itself which is all too familiar suddenly gets strange and uncanny and acquires some sort of monstrousness. In Germany, Wagner forbade applause. He had quite a lot of issues with the fact that people were used to applauding during operas. He even intentionally composed solos or arias in a such a way that people couldn’t applaud afterwards.

A problematic I was also thinking about in CLAP was to make a gesture which is not purely critical but also not purely affirmative. I wanted to see if you could create the classical dramaturgy of a piece without any feeling of catharsis. Can we create a functioning performance without any content? There is something rhetorical about clapping.

Andrea: In this essay, I posed the question whether we should call this performance “participatory” and suggested that Guy’s Debord’s Manichean dichotomy of the “active vs. passive” viewer (from Society of the Spectacle), which governs participatory art discourse, is too schematic, over-determined, or binary. Did you have any thoughts on this?

Christoph: This type of classical Marxist theory (Debord) is very clear about what they consider “non-alienated” labor. However, there are situations where passiveness can be active, passiveness can be performative or, paradoxically, where activity can be passive. Take the case of camouflage. Camouflage is in a sense both active and passive. The experience of an audience is perhaps too ghost-like to be captured by “active vs. passive viewer” categories. This is Kate McIntosh’s idea, the notion of the audience as ghost.

Another concept I have been thinking about a lot lately (which is neither strictly passive or active) is Marcel Duchamp’s notion of inframince (translated as “ultra-thin”).

Andrea: By “inframince” I assume you are referring to ephemeral, indeterminate or ultra-thin phenomena, fleeting moments when different elements meet, merge, or change one another at the borderlines of the perceptible, creating a phenomenology of the imperceptible [10]. Paul Matisse called inframince the “very last lastness of things… [the] frail and final minimum before reality disappears.” [11]

Christoph: Yes, Duchamp gives examples of the heat of a chair when somebody just got up out of it, or the smell of smoke blown in the air. Let’s take remembering. What is remembering in terms of an action? Remembering is neither strictly passive nor strictly active. In the part of CLAP where the performers are closing their eyes, I asked them to remember in different time scales the last time they clapped. Remembering as a gesture is very present in clapping.

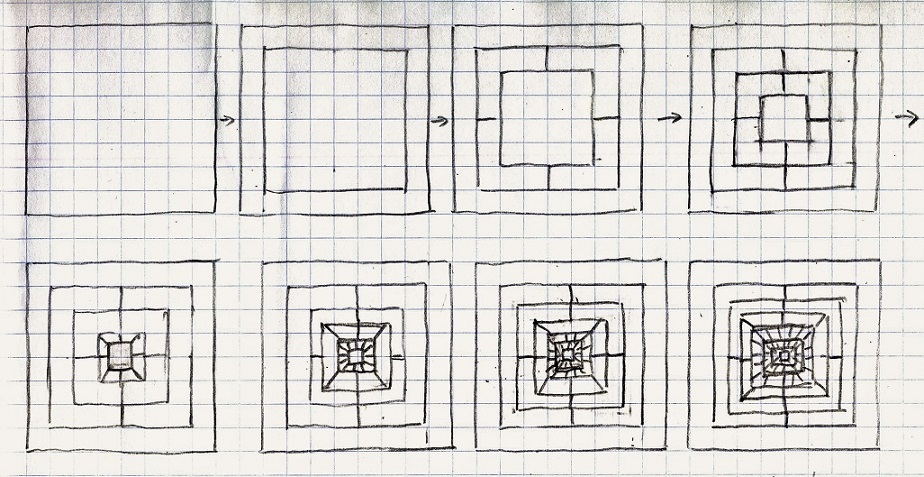

There is another way inframince (or a barely perceptible change in a system) is relevant to CLAP. For example, at the point in the performance where there is a long crescendo, you can’t really say when it is that you recognize it as clapping. Before you recognize it as clapping it is rain, it is water, it is people fucking. But it doesn’t jump into the regime of signification because it was something else suddenly becoming something else. It melts from one to the other. Clapping as a collective process is full of these nuances, which you know from all your clapping experience. Also at the end of this performance, where you decide or time at which moment you will start clapping, the scaling of the decision-making is on a micropolitical level; because what brings you to the fact that you clap at that moment is basically a re-shifting or remembering of pure collective engagement, but on an ultra-thin (inframince) level.

Andrea: I first came across CLAP (and your work) when you were one of 5 artists, out of 171 applicants, selected for the “Counterhegemony: Art in Social Context Fellowship” program I curated at Contemporary Art Centre Vilnius. (I was the sole person on the selection committee). Since then we were in dialogue off and on about the evolution of CLAP, and we gave a collaborative talk together about CLAP at Sorbonne Université VALE (Voix Anglophones Littérature et Esthétique) in Paris. I recall when I conducted the one-hour interview with you for the fellowship program, you said something intriguing, which is that you don’t aspire to or seek “stability” within a system (I think you were talking about performance as a “system” and you were saying that you don’t aspire to create “stability” within that system). Can you elaborate on what you meant?

Christoph: What I am interested in as aesthetic research is basically to open up spaces where you can “perceive” perception or how your perception functions, and also maybe to shift the way you are used to experience or see or judge the way you read things. Liminal techniques of expanding perception are often discredited as “not functioning”. I like to throw into question when we judge something as “not functioning.”

I am interested in the processional. For example, within different temporalities of doing or of interaction or embodiment, there is always a past gesture/action which perhaps started as symbolic or “meaningful” but can fade into a meaningful meaninglessness, or something which is not so loaded with meaning, and I am more interested in these processes.

These processes are not in a strict, direct sense “readable” as some form of narration or as some form of aesthetics. But for me in a phenomenological sense they are much more about how our perception functions. Because it is constantly unstable, and it is constantly re-shifting itself. That is a process which, on a micro-level, is highly performative and which I am very interested in. I am not so much interested in signification in terms of specific actions, specific speech acts, specific staging of doings; but more in this way that you have to figure out what you see yourself and why, and how that is then related to what you perceive as “normal” to perceive.

I also find interesting the question “Was it wrongly directed?” (i.e. when you cannot tell if a performance was “wrongly directed” or not).

I was also much inspired by watching Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, where you just see the living temporality of people passing and all the things they do in-between when they seemingly forget they are being recorded, or then they realize they are being recorded so they re-adapt to the image of themselves, or the image they want to project of themselves.

Andrea: What you have just said about how there is an innate instability embedded in the processes of our perception which is highly performative, as well as your comment about how you are not interested in “specific actions, specific speech acts, specific stagings of doings”—I think both these points are quite crucial to your concept of the “performative readymade.” Your concept of the performative readymade is that you don’t need to “fabricate” a performance (with specific stagings, specific acts, etc.)—because there is already a performativity embedded in the instability of the processes of our perception. By far the most ingenious thing I have heard you say about CLAP is that because you view the clapping performers as the readymade, you view the live audience as an installation. I find intriguing that you see the people who have come to see your performance as a (temporary) installation in the theater. (Of course, Duchamp had different categories for the readymade, including: semi-readymade, aided readymade, assisted readymade, provoked readymade, distanced readymade, reciprocal readymade, sad readymade, sick readymade. [12] But we can construe CLAP as a performative readymade in the sense that it was not about fabricating a performance, but making visible the “readymade” performativity already inherent in our shifting processes of perception. It also relates to how you didn’t want to use professional actors for the piece, and that it was very important for you that you use non-professional non-actors as the clappers. Just as you said you are not interested in “specific speech acts, specific stagings of doings”—it seems for this piece you were also not interested in trained actors fabricating xyz; you wanted real people to do real clapping just as they would in real life.

Now I would like to address how you mentioned earlier the notion of the audience as a ghost. Can you elaborate on that?

Christoph: CLAP was an exercise to make the audience as a fading dispositif. One tends to become disembodied in the dispositif of the audience. The audience is present as a dead body—it’s a ghost. It’s not incorporated. What comes after the death of the audience is the audience. The notion of audience as a dead body brings us to the question of whether it was alive at any point in its own in history. There was always something about it that was chimeric, almost machinic, beyond-the-living—in some way the bourgeois audience was always a dead body.

Andrea: I also would like to ask you about something you said in a past conversation, which is that “perhaps the audience as a figure was a bad idea.” Can you elaborate on that?

Christoph: In antiquity, the choir is full of violence, it is a sphere of sacrifice, of harsh energy drives, of lethal stonings. Every choir or community has a dangerous tendency towards the excesses of a collective. This notion of a crowd, a choir or an audience as a synchronized mass (which is still the case for theater)—maybe it is a bad idea. Maybe it’s more interesting to think about choirs which are de-synced so that different temporalities can act together, but in a format that is not synchronized.

Andrea: In my essay, I used the phrase “heteronormative dude clap.” I would like to propose that a gay male aesthetic of clapping differs from straight male clapping. Of course this is a generalization and there are always exceptions, but at least in the U.S. there is a way a straight man sits in a chair, a way he holds himself in his body (one could call it “normative” or masculinist) and there is a way a gay man sits in a chair, holds himself in his body (and most importantly, the way he speaks) that is completely different and distinguishable from a straight man—but it is almost impossible to explain in words. One thing—there is perhaps a gruffness, a brusque utilitarian attitude towards one’s appearance amongst straight men; whereas with gay men, there is perhaps a levity, a stylized performativity. Perhaps one could compare it to Baudelaire’s “dandy” in 19th-century Paris, someone placing himself in a separate sphere of personalized aesthetics. The notion that gay men have a different subculture than heterosexuals and that you can tell whether a man is gay based on their bodily affect, their relationship to their appearance, how they carry themselves, etc., is also deeply ingrained in American popular culture. For example, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy was a TV show where gay men give a “makeover” to a straight man’s way of dress or decoration of their apartment.

Another example, I was walking down a street in Manhattan once with a friend (my friend was straight, but he had been raised by two gay men married to each other and was attuned to gay male culture). We passed by the window of an athletic gear store which had two (male) plastic mannequins in the window dressed in very stylish athletic gear. My friend stopped me, told me to take a look at these two mannequins and asked me, “Do you notice anything in particular about these mannequins?” He said that the way the mannequins were standing and their posture told him that they were gay men. In San Francisco in the 1970s, in a neighborhood called “the Castro”, there was a “movement” or trend where gay men started to wear black leather and to take on the figure of the hyper-male “rough” man—a sort of camp version of a performative hypermasculinity—which became a gay aesthetic. My friend said that the way these plastic mannequins were standing told him that they were modeled on gay men of this period.

I bring this up because in the Ballhaust Ost version of the CLAP performance in Berlin, there were 2 men who clapped in a more traditionally masculine (macho) way, and one man who clapped in a way that could be construed as more “queer.” Do you think it is absurd to propose that there is a difference between how gay and straight men clap?

Christoph: I think it is a little too easy, since there is a whole cultural history and it is very diverse and there is re-appropriation of gay identity and culture. I don’t know too much about it, but I know it is complex. At the end of 1920s, specifically in the communist state, there was a whole culture of revisiting forms of manhood by non-heterosexuals from a communist perspective, it has a lot of history. What you are talking about is basically a re-appropriation of femininity from gay men—it is re-appropriation of culturally-coded femininity through a male body. And of course with this reappropriation there comes a bigger self-consciousness about your own image because that is traditionally the domain of the female. Even though it has shifted a lot, this was traditionally a blind spot of the heteronormative masculine—he was not thinking that he has to be conscious about his image in a specific sense.