Addressing a congress of architects in 1963, the Professor of Turin Polytechnic University, Leonardo Mosso, declared: “Unfortunately, we must state that at this time there is no existing architectural culture”. [1] Mosso would later draw a distinction between “culture” and “ac-culturation” and would argue that the former is often replaced by the latter when what is implemented in the cultural field is not the creative will of the people, but that of a select few, whose will is imposed on the majority. [2]

If, in the 1960s, there was no architectural culture, there was certainly a tradition. From the 1960s onwards the thought and the work of Mosso, who was an artist and theorist as well as an architect, entered into a complex and interesting relationship with the concepts of tradition and the avant-garde on the threshold of Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde and the closely related ideas of Manfredo Tafuri. I will examine Mosso’s concepts of structural design and sustainable programmed architecture, as embodied in museum and urbanistic projects, through the prism of their relationship to a range of architectural, cultural and scientific traditions.

Italian rationalism

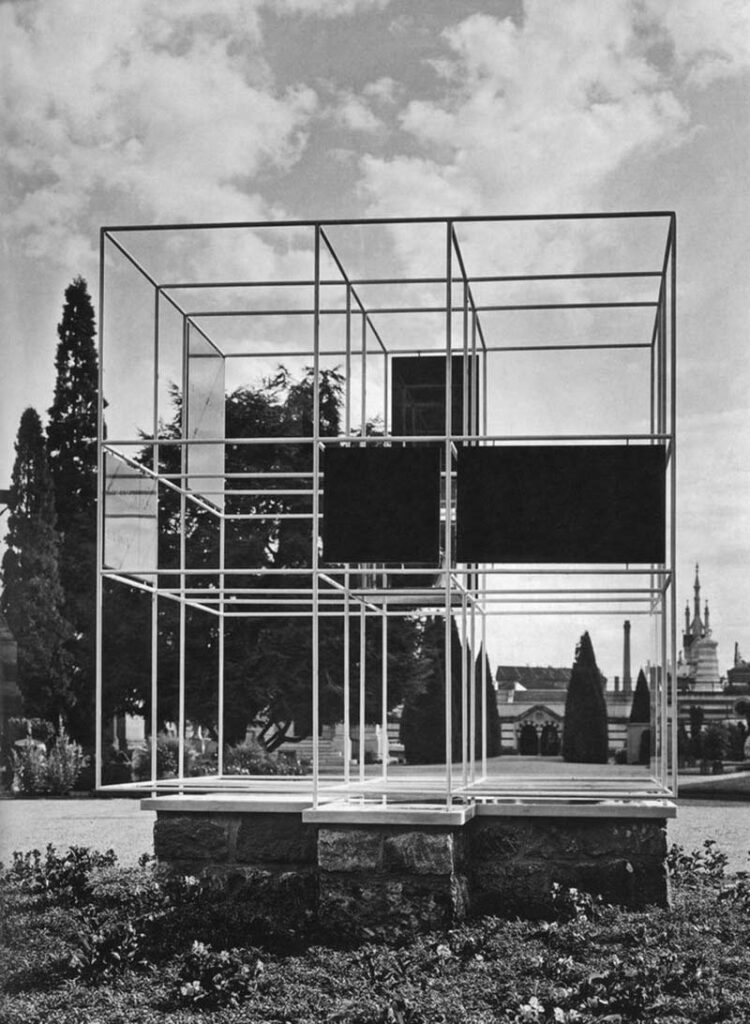

The first tradition of relevance to Mosso is that of rationalist architecture, specifically of Italian rationalism, which faded into the shadows at the end of the 1930s, oppressed by fascist monumentalism, but still lingered on in the post-War years as a memorial to a future that was at once impossible and annihilated, symbolized by the Monument to the Victims of Concentration Camps created in a Milan cemetery by the Italian architectural group BBPR in 1946. Apart from its literal purpose, the Monument can be read as homage to ideals that were not destined to come true in principle (especially if viewed, not even from the 1960s, but from the disillusionment with utopias that ensued in the 1970s). Since the 1930s, pure rationalism had been criticized as an expression of liberal European culture that was incapable of dialogue with reality. [3] But its formal language would leave an imprint on the architecture of Mosso, whose career began in the early 1950s in the studio of his father, the futurist and rationalist Nicola Mosso. Father and son together designed the Turin church Gesù Redentore (1954–1957), with its clear reminiscences of the mathematically determined architecture of the Cartesian Guarino Guarini and his Chapel of the Holy Shroud, also in Turin.

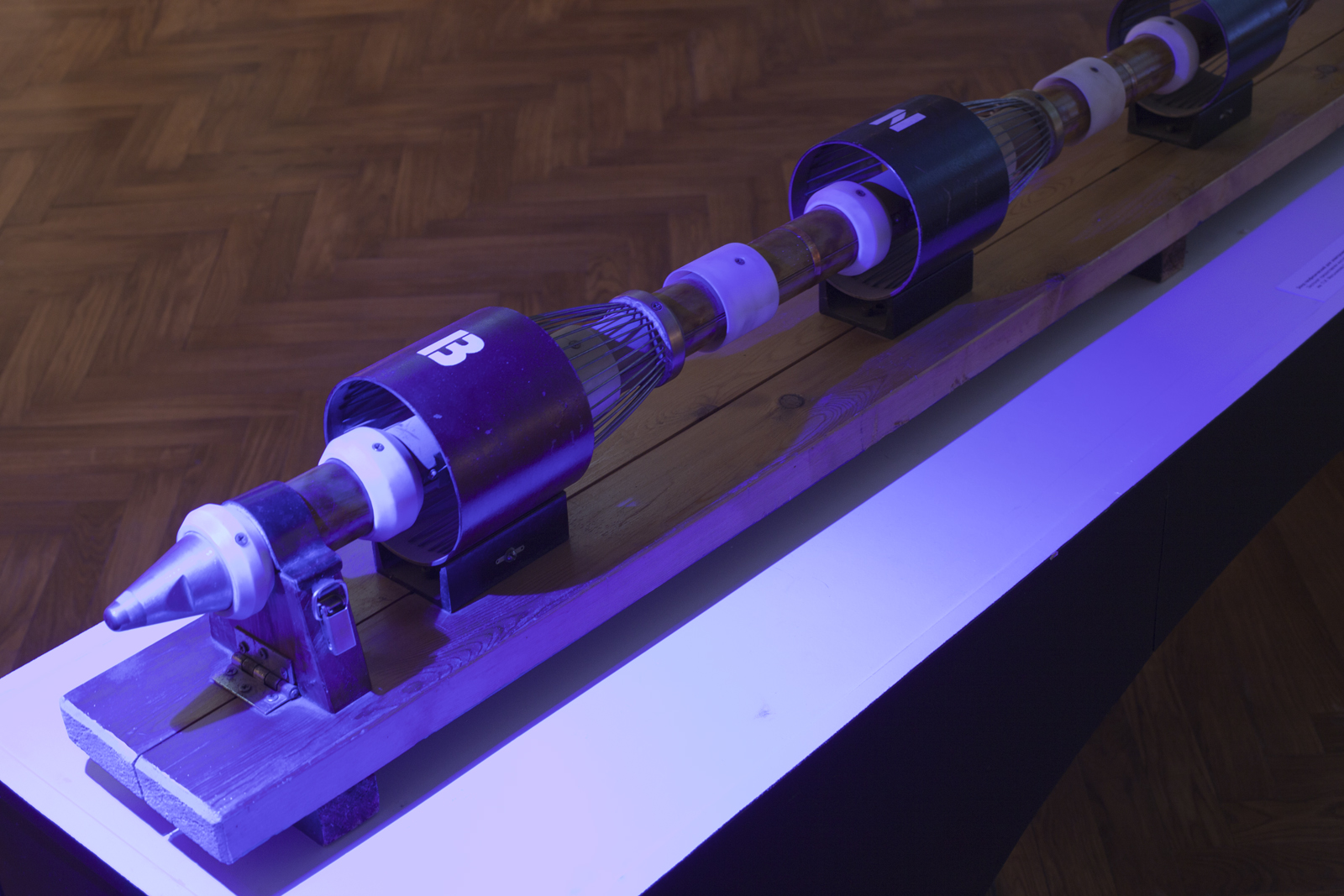

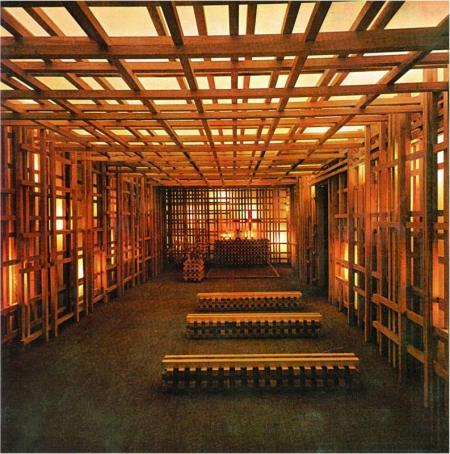

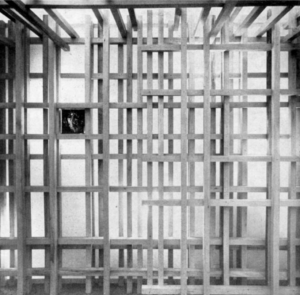

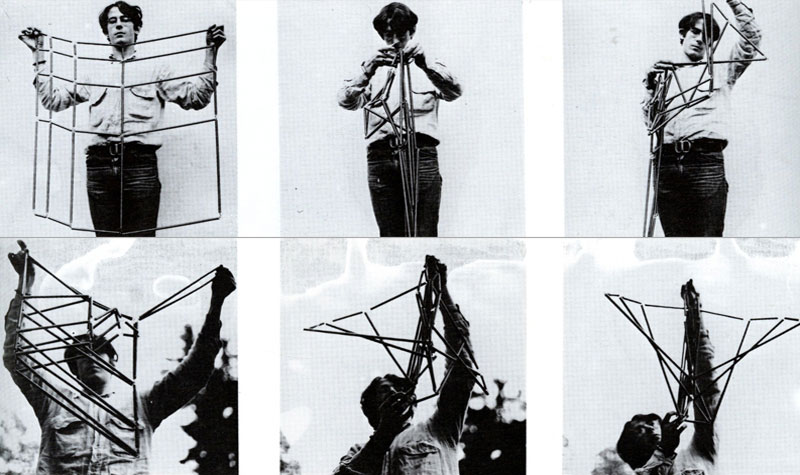

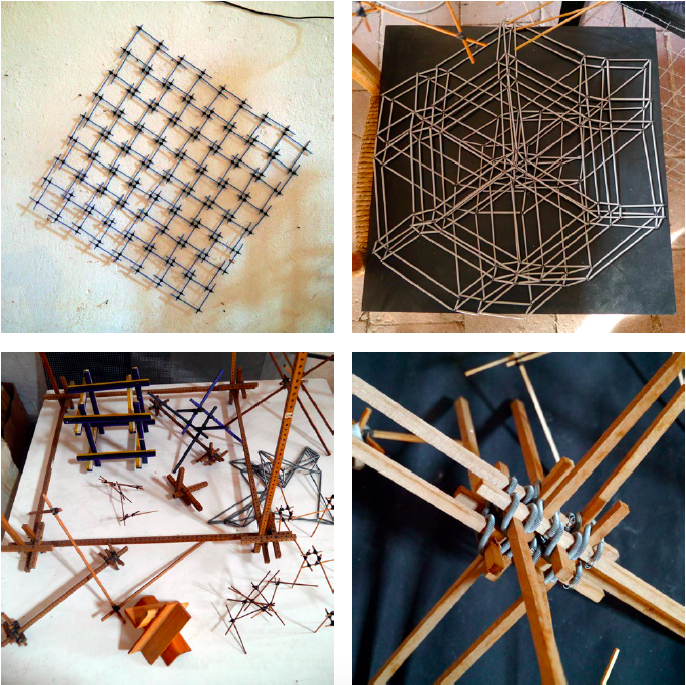

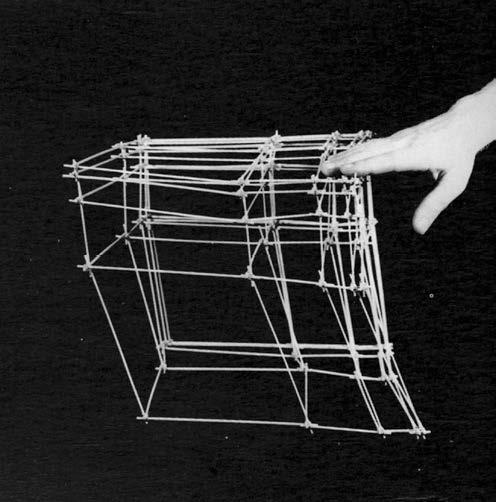

The visual cues of Mosso’s architecture have a clear affinity with such 20th century rationalists as Franco Albini and especially Edoardo Persico. Mosso weaves a new musculature of semiological theory and critique of capitalism onto the familiar skeleton-grid, transforming the structure into a self-governing organism that opposes the absolute rule of the architect. In his 1969 Manifesto of Direct Architecture, Mosso sought “to overcome the violence of architects and come to a direct architecture, to overcome the violence of power and come to direct democracy.” [4] Other manifestos of programmed architecture, notably “Self-Generation of Form and the New Ecology”, [5] would come later. But their main principles were already set out in one of Mosso’s first independent projects, the Chapel for the Artist’s Mass, built in 1961–1963, which survives only in photographs. [6] The Chapel used a modular architecture of geometrical shapes reduced to their simplest form. In a style similar to that of Edoardo Persico, Mosso places an image (of the Madonna by the artist Carlo Rapp) in one of the modules. (It is interesting to note that Persico himself, in his 1933 article, “Italian Architects” had declared: “We believe that Italian rationalism is dead”). [7] The face of the Madonna, inscribed in a square, appears highly fragmentary. Judged by the standard of altar images, and in combination with the framework that defines the wall surface and holds the image, the effect is close to an Orthodox iconostasis, where the contours of the painted body often seem to support the frame. The other modules of the Chapel are empty and transparent (purified, like the elements of language in structuralism, which was a base theory for the 1960s and, in particular, for Mosso) and what knits the structure together is their linkage – a nodal point or joint. From the Artist’s Chapel onwards the development of this joint was the key task of Mosso’s work. The basis of the universal “elastic” joint, which holds the structure, is a sliding mechanism of elements fastened together with compression straps. In other, later models, there is a void at the centre of the joints; at their ends there are metal rings, which allow free rotation of the structure. [8] Numerous experiments that Mosso carried out with colleagues and students (teamwork was fundamental to his practice) produced a theory of the “virtual” joint, where virtuality is an almost philosophical concept [9] of multidirectional elements and limitless possible linkages.

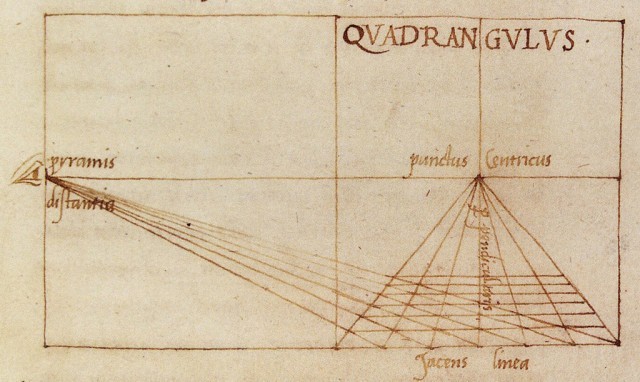

Mosso calls these regulated connections “post-Cartesian”, which implies the preservation in his world system of rationalism and a mechanistic philosophy, but with two important provisos. In the first place, the void, which Descartes rejected, is admitted and, moreover, takes precedence over substance and is the bearer of the functions, with which Mosso wants to endow his architecture. Due to the entropic nature of the joints proposed by Mosso, subsequent modifications to the structure re-record those made previously and cannot be undone, [10] leaving the trace of each person who influenced its transformation, but not fixing it in a stable state. Each iteration is conditioned by others in this sequence, but is associated with them only by memory (“The memory of the computer for a programmed city formed directly by its inhabitants” is one of Mosso’s “margin slogans” to his article on self-generation of form). [11] The second, equally important proviso of Mosso’s Cartesianism is rejection of the antinomy between mind and body, which is the mainstay of Descartes’s system. As Mosso declared in 1963: there is no “irreparable conflict” in the relationship between mind and body, any more than there is a conflict between idealism and positivism. [12] For Mosso the ultimate task of such a structure was the transfer of control from architect to users and elimination of the contradiction between man as subject and as object.

Mosso’s rethinking of Cartesianism – enriched, as will be seen below, by cybernetics – involves the elimination of antinomies, making the human being into the subject of architecture and enabling the emergence of a new forms of social and spatial organization, “from the bottom up”, entailing a crisis of elitism. In Mosso’s own words: “This inversion, if carried to its logical conclusion, would bring the notion of ‘intellectual’ and ‘expert’ to a severe crisis, turning it from the function of a component in a directing elite, which always somehow tries to direct people even when its tendencies are socialist, into that of effective service for popular construction.” [13]

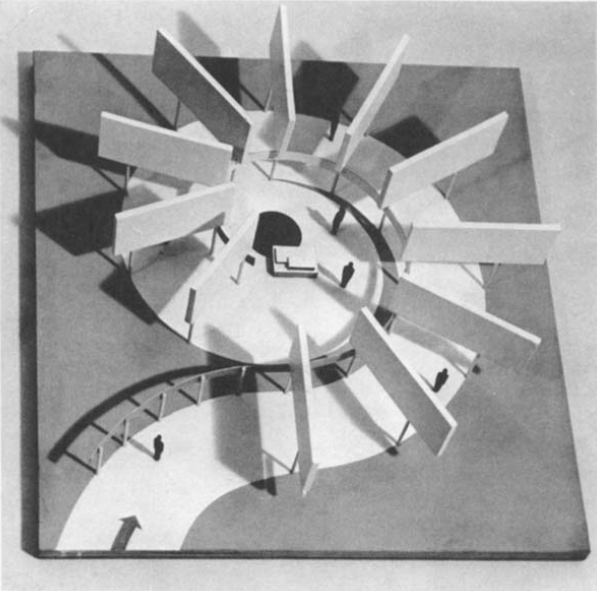

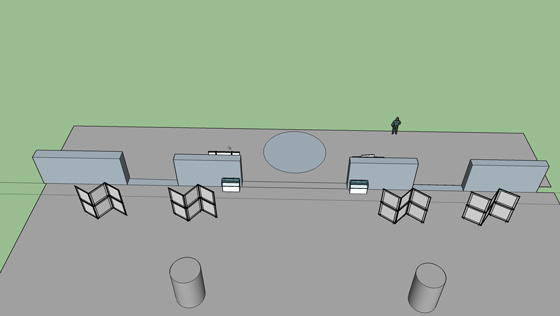

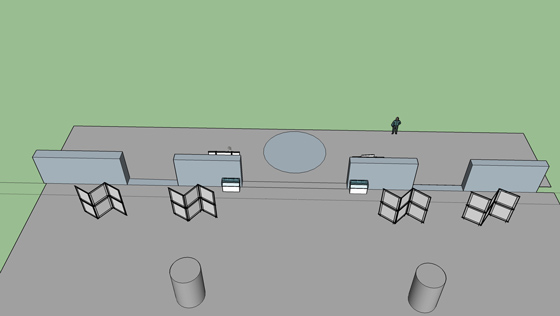

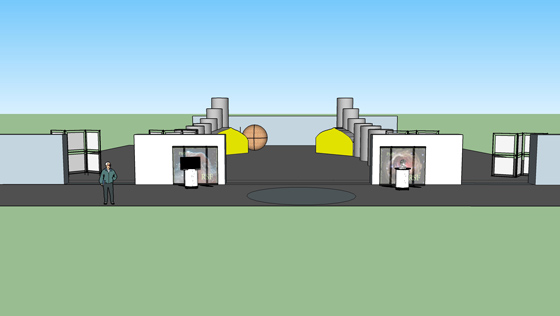

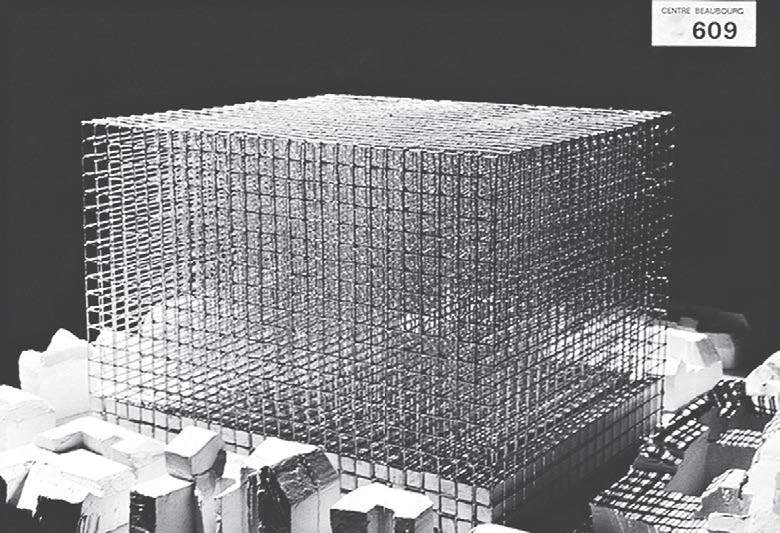

The transition from statics to dynamics represents another task: the limitlessness of formal transformation is identical with the variability of the scenarios of social transformation, which can be carried out by the same people. All of these principles were behind the “Commune of Culture” project of programmed architecture, which was Mosso’s entry in 1971 to the design competition for the future Centre Pompidou in Paris. What Mosso envisaged was an architectural and urbanistic organism controlled by a collective (a community) and developing thanks to structural processes in its cells, each of which contains the possibility of the most various configurations.

Structural and semiological approach

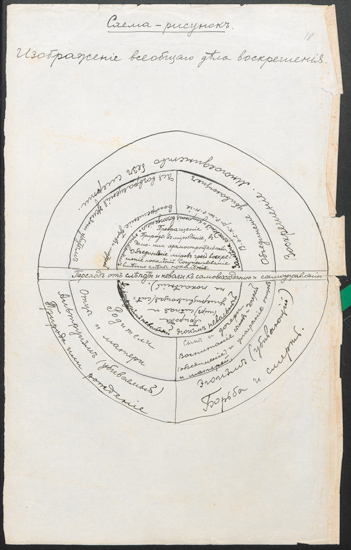

Mosso equates the role of an architect with that of a linguist, who reveals certain mechanisms (the linguist in language, the architect in buildings) instead of describing the possibilities of an element’s functioning. [14] Put in linguistic terms: the basis of syntactical structures in a language is not the component (which is intentionally treated as inexpressive and devoid of a priori meaning), but what links them – the “joint”. [15] Mosso’s idea is that these mechanisms come into the hands of users and are activated by them, because architecture is the least autonomous sphere of culture and society. This is the new tradition of structural-semiology, which was taking hold in the 1960s and which the architect encountered and began to work with at its origins (unlike his encounter with the established discourse of Italian rationalism).

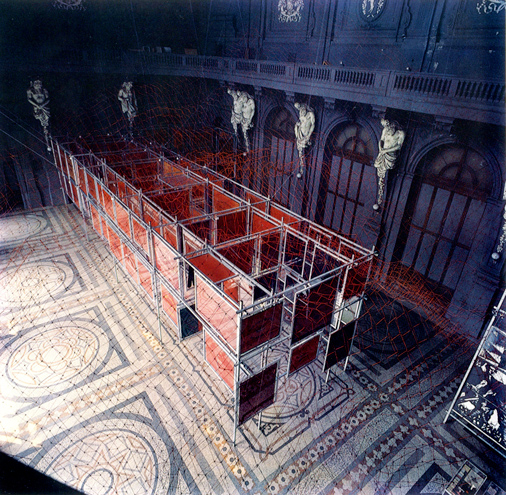

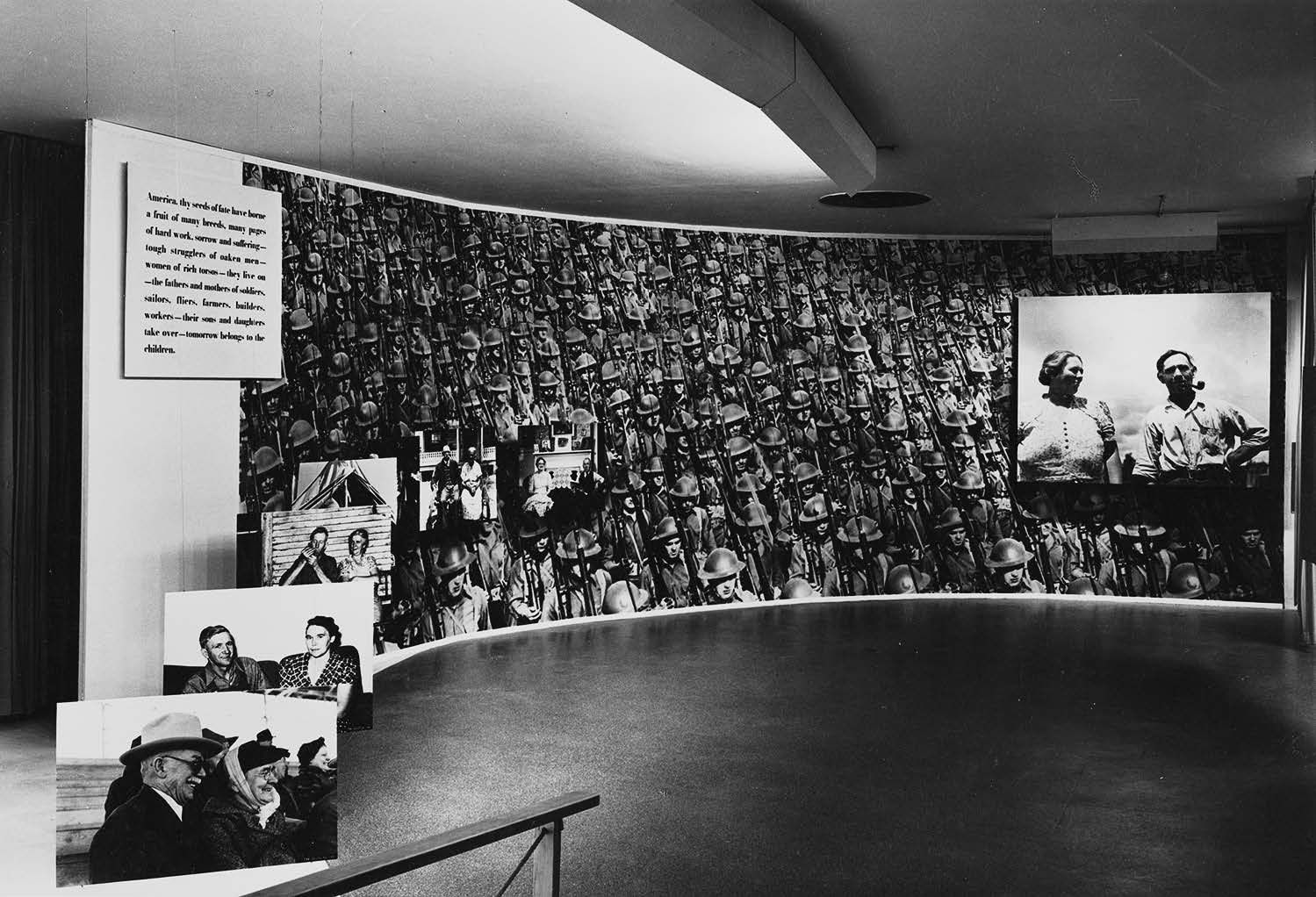

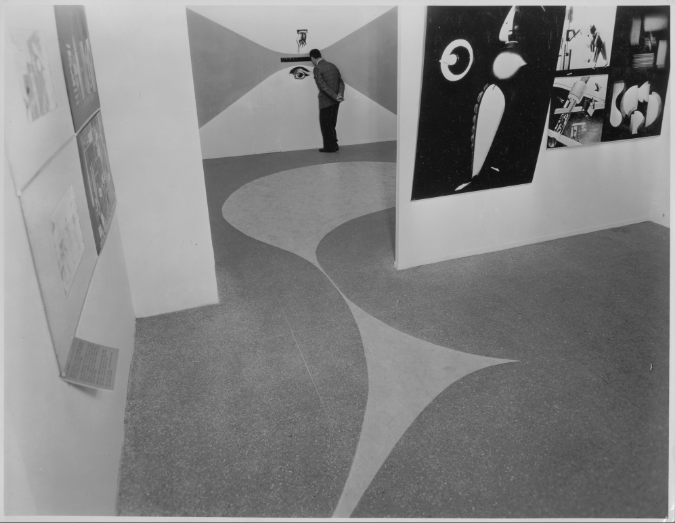

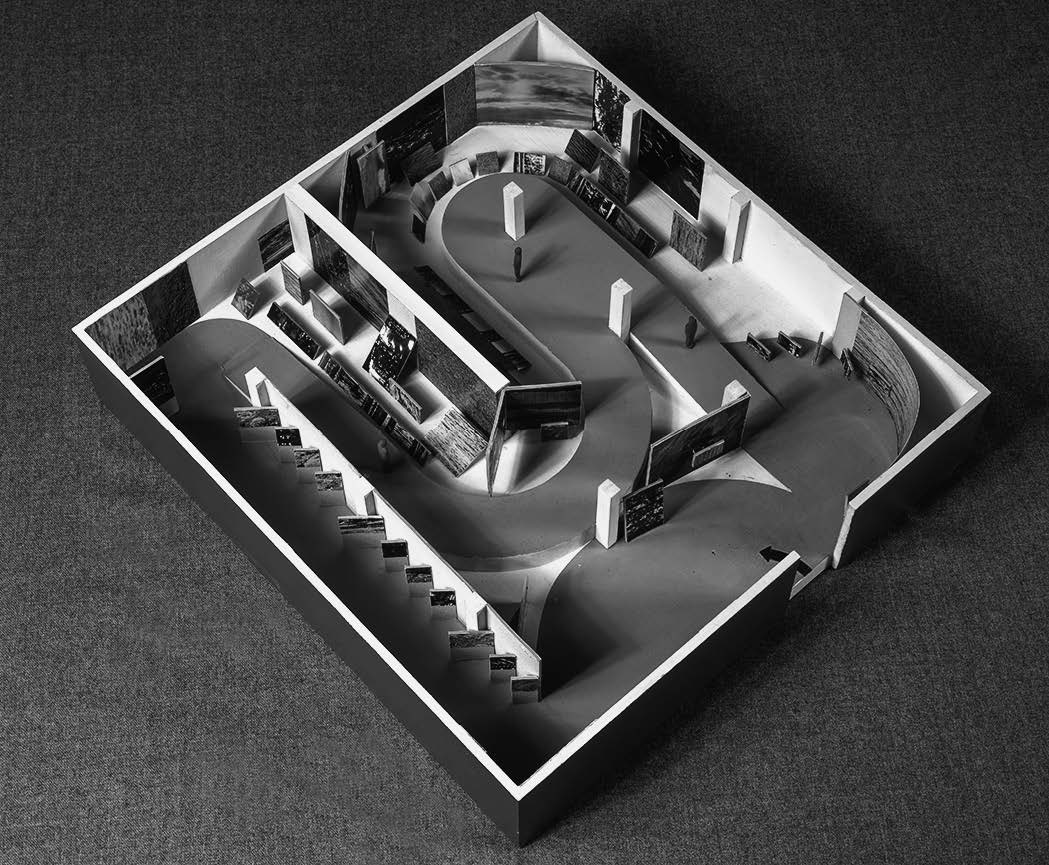

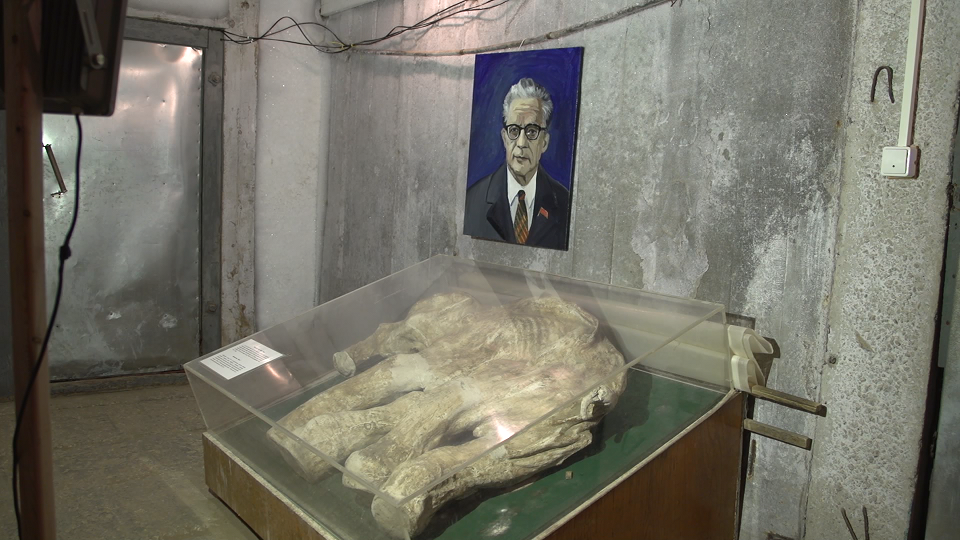

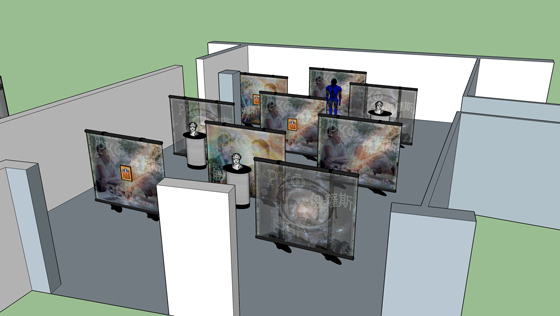

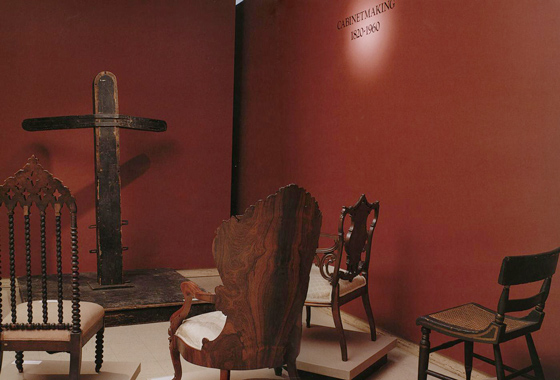

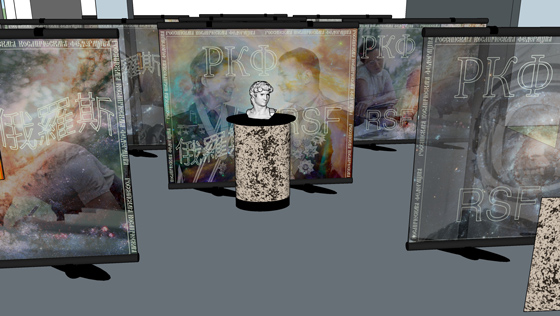

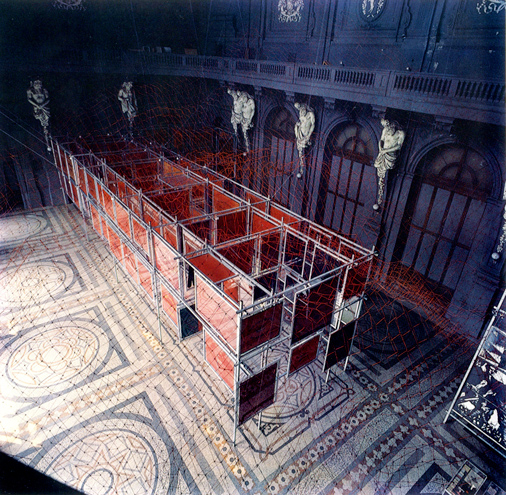

In the 1970s the publicist and anti-fascist activist Franco Antonicelli asked Leonardo Mosso to work on a project for the Museum of the Resistance (the architect had already designed several museum and exhibition projects by that time). [16] Creation of the Museum in the Palazzo Carignano in Turin occupied Mosso from 1974 until 1977. The idea [17] was to divide the Museum into three parts: a first part that the designers called “symbolic” or introductory; a second consisting of a gallery with exhibits, the “Corridoio dei passi perduti” (Corridor of lost steps); and a third part offering a multimedia centre for research and education. [18] The same elastic joints, made from neoprene are used in the structure that contains the Museum exhibits and in the Red Cloud – Mosso’s floating sculpture, made from wooden elements painted red, that leads into the exhibition. The Red Cloud looked out onto Turin’s Carlo Alberto square through the high window openings of what, in the 19th century, had been the hall of the Italian parliament (before its relocation to Rome). Mosso considered Red Cloud to be a milestone of his conceptual and formal explorations. In 1981, the sculpture was included in the exhibition held by the Piero Gobetti Study Centre, Another Italy in the Banners of Workers. Symbols and Culture from the Unification of Italy to the Advent of Fascism, which displayed the political insignia of a broad range of communities, from Catholic organizations to feminist groups and left-wing parties, anarchist groups, trade unions, etc. (the exhibition was made possible by Carla Gobetti’s discovery in January 1978 in the Italian state archives of about 190 flags and banners confiscated and exhibited in Rome by the government of Benito Mussolini at the Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution, held in 1932 to mark the tenth anniversary of Mussolini’s March on Rome). [19]

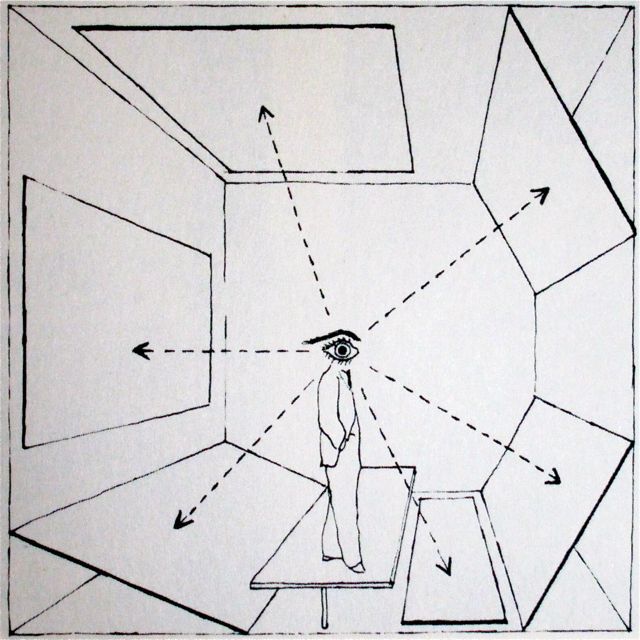

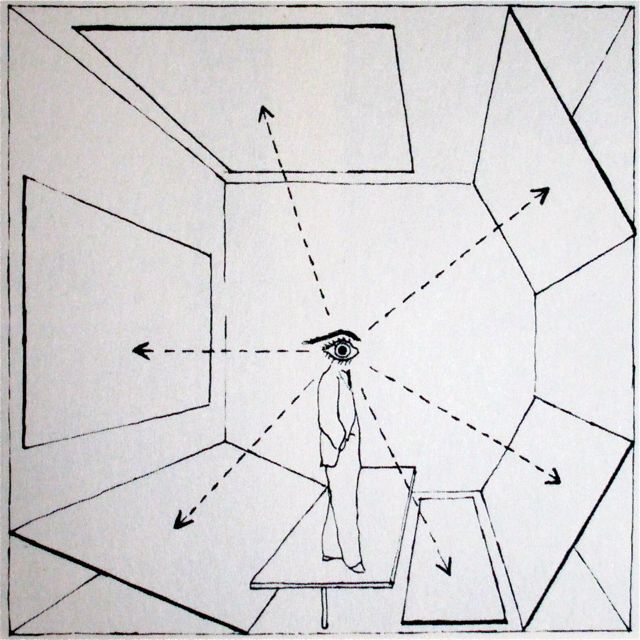

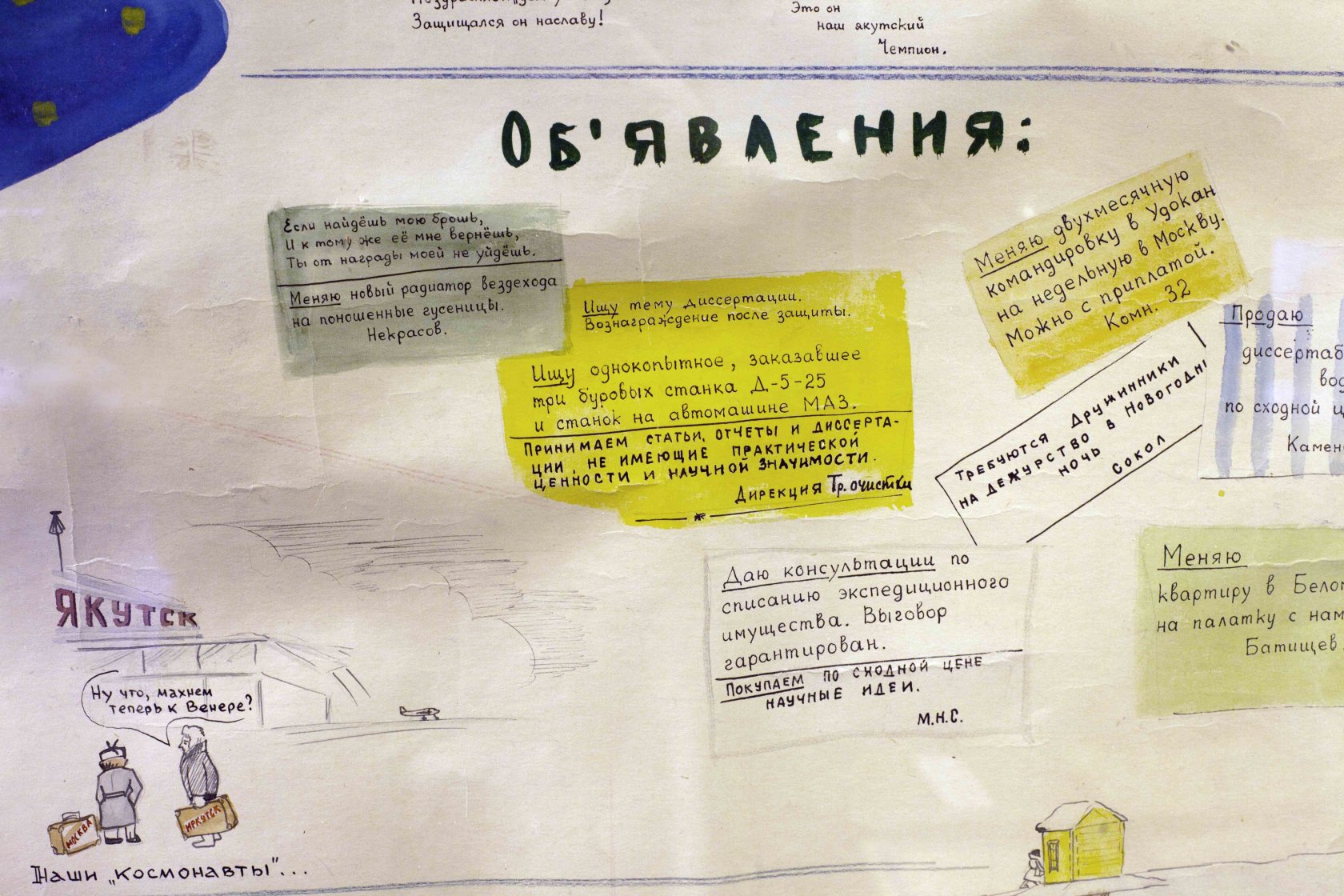

The models that Mosso built following the example of syntactic relations reflected the influence of structuralism and a belief in the possibility of new subject-object relations. In his text “Semiotics and Design, Consciousness and Knowledge. The Museum of the Resistance in Turin”, Mosso states that “research and experimentation with decoding, classification, documentation and communication, with the semiotic order of various object and document forms, with the legacy of those messages that are already available” are a necessary condition – the sine qua non – of museography. [20] Flags and banners are themselves sign systems. Mosso was the architect of the 1981 exhibition and his sculpture served as an overhead vault for the exhibits. Prior to the exhibition opening the curators carried out work to decipher the emblems, symbols, slogans and use of colors in the exhibits, tracing their transformation through the history of various labor movements. The work uncovered much that had not previously been known about political trends in Italy and about propaganda techniques. The aim was to help reformulate (albeit broadly) the language of the workers’ and peasants’ movement, reconstructing the tradition of each specific symbolic element and the overall, collective expression of will and thought. [21] And yet, both in 1974 and as a frame for the 1981 exhibition, Mosso’s sculpture seemed to be in clear contradiction with the structuralist approach. The red color and the cloud amount to what Umberto Eco called the “anthropological code”, that is, “facts relating to the world of social relations and living conditions, but considered only insofar as they are already codified” and, therefore, reduced to phenomena of culture. [22] They return the viewer to an established historical reading of the sign, and “the appeal to the anthropological code risks (or at least seems to risk) destroying the semiological system that rules our whole discourse.” [23] Red unambiguously marked the labor movement that was dear to Mosso and that was strongly present in the cultural life of Italy in the 1960–1970s even without the occasion offered by the exhibition, as manifested, for example, by the Marxist magazine Quaderni Rossi (Red Notebooks), published in 1961–1966, and the autoreduzione movement, in which left-wing protesters refused to pay market prices for goods, instead offering what they considered a fair price (the movement began in 1974 at the FIAT car factory in Turin).

The image of the cloud is even more complex, but also rooted in the historicized past. Hubert Damisch’s book A Theory of /Cloud/, published in 1972, had considered the multi-level and powerfully semiological nature of the concept of the cloud, viewing it as inextricably linked with the architecture of a powerful signifying space, usually bordering on the sacred, as in the case of the flags presented at the 1981 exhibition. [24] (Mosso himself spoke of the need to “‘desacralize’ the museum itself “, its appropriation by the people and the transformation of the self into a historical subject, to be achieved primarily by the decoding of documents). [25] In his book Damisch analyzes the functioning of the cloud as sign in different periods and cultural contexts and reaches interesting conclusions: on the one hand, the cloud, as a field, “has no particular meaning in itself; its only meaning is that which stems from the relations of consecutiveness, opposition and substitution that link it to other elements in the system”. [26] On the other hand, as Damisch says elsewhere in the book, the cloud always testifies to the closed nature of a system, “since it is the sign of opacity … the limit of representation, of what is representable.” [27] Despite Mosso’s fascination with open systems, despite his optimism about the potential of architecture to be a vehicle for social transformation, his self-positioning and his positioning of cultural production in the museum might be seen as reactionary in comparison with his contemporaries who at the same time were taking further the efforts, initiated by the historical avant-garde, to destroy the border between art and life. For Mosso, the Museum of the Resistance, “like potentially any other urban structure,” “starts from its sector of competence,” [28] which is to say that it is, essentially, autonomous. This is not to say that the museum should not be a living and contemporary structure, but “living” here means “museographically living”. In the words of anthropologist Alberto Mario Cirese, quoted by the critic Arturo Fittipaldi in his article on the Museum of the Resistance: the museum must admit that it is a metalanguage, which will be adequate to life on condition that it is aware of its essence and its limitations. [29]

So Mosso, operating within the tradition of structuralism, consciously departed from it and entered the tradition of semiotic reading, which he considered to be a necessary condition “for accessing a historical understanding of past reality” [30] and also for dialogue with the viewer about contemporary problems. By thus rejecting the accepted historicism he agreed with Hubert Damisch that the history of culture needs to be presented as a dynamic model and to be understood as a continual return to the source, and that it is akin to continuous movement within a certain given space. In such a model there can be no contrast between tradition and the avant-garde, and this acceptance of their reciprocity entails agreement with the pessimistic conclusions of Peter Bürger and Manfredo Tafuri. It can be argued that Mosso performed a decomposition of tradition (specifically a “decomposition” and not a “deconstruction”, because in the latter, according to Derrida, the generation of meanings occurs thanks to the interconnection of elements, while the former implies only flexibility in their use), separating traditions into various ideological and formal elements, thereby levelling their temporal aspect, their extension, and hence also doing away with the division into “old” and “new”, “good” and “bad”, “productive” and “unproductive”. On the one hand, the effect of the Red Cloud was to destabilize the visitor’s perception by its alien nature in the realm of the visual, but, on the other hand, the Cloud remained neutral, transparent and non-invasive towards the enclosing architecture, with its frescoes on the theme of the commonwealth of art and science. [31]

Organic architecture and programming

The tradition of organic architecture in its relationship with techno-positivism and the concept of a programmable city was also of decisive importance for Mosso. The architect came into contact with organic architecture when he was working in the studio of Alvar Aalto in 1955–1958. Its ideas were championed in Italy by Bruno Zevi, who was deeply influenced by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, and the title of Zevi’s seminal work Towards an Organic Architecture (1945) refers explicitly to Le Corbusier’s Towards Architecture (1923). Zevi was categorical regarding what he considered to be a “modern language of architecture”, and particularly that it must reject geometrism and, most of all, symmetry: “Once you get rid of the fetish of symmetry, you will have taken a giant step on the road to a democratic architecture”; [32] “The public buildings of Fascism, Nazism, and Stalinist Russia are all symmetrical”; [33] “Symmetry is a single, though macroscopic symptom of a tumor whose cells have metastasized everywhere in geometry. The history of cities could be interpreted as the clash between geometry (an invariable of dictatorial or bureaucratic power) and free forms (which are congenial to human life).” [34] In Zevi’s view, if such great masters as Aalto, Walter Gropius or Mies van der Rohe returned to symmetry as to the “bosom of classicism”, that was an act of surrender on their part and an admission of their inability to create a new language. Organic architecture, like Italian rationalism before it, saw itself as the antithesis of monumentalism and its myths. [35] Its principal ambition was to return to a humanistic measure, which was especially important in the context of post-war reflection, and to advance the democratization of culture and society. Organic architecture believed that this required a denial of rationalism and functionalism, seeming to forget that they had had (and still retained) their own humanistic measure, but one based not on form, but on proportion.

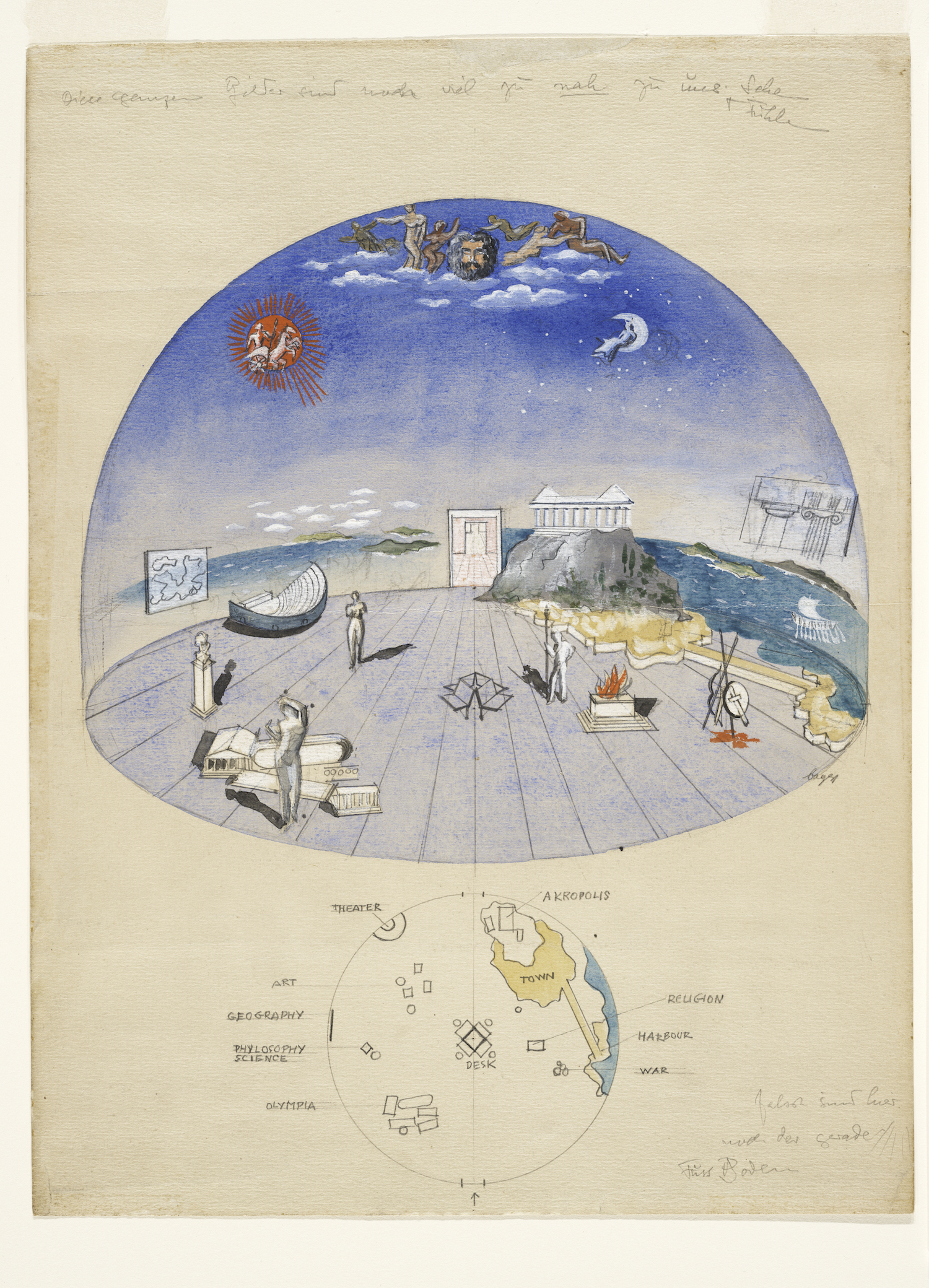

A Congress held in 1951 in Milan, as part of the 9th Triennale, was devoted to the theory of proportion and was accompanied by an exhibition of studies in proportion. Two of the leading theorists of proportion, Le Corbusier and Rudolf Wittkower, both took part in the Congress and deep disagreements between them ensured that the atmosphere was tense. [36] Construction of the exhibition, designed by the young architect Francesco Gnecchi-Ruscone, was in the best rationalist tradition, using iron pipes and in accordance with the golden ratio, allowed the exhibits to be viewed from a variety of angles, including from the bottom up.

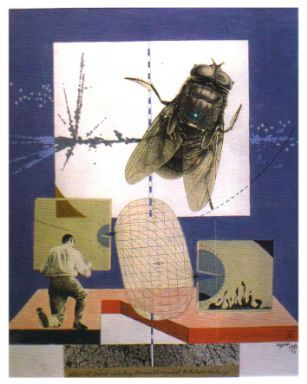

Few have been able to bend the parallel trajectories of rationalism and the organic to a point where they meet. The most notable effort in this direction is the “biotechnics” theory of the Austrian botanist and microbiologist Raoul Francé. Biotechnics, in Francé’s understanding, means the “technology of life”, a concept that fits very well with Mosso’s Cartesian mechanicism. Francé, like the rationalists, reduced the diversity of biological and technical forms to basic elements: “What is perhaps most amazing is that all these countless needs for movement, all the alterations of appearance and way of life were met and produced by the application and varied combination of just seven basic technical forms: crystal, sphere, plane, ribbon, cylinder, screw and cone.” [37] Man, Francé believes, can only invent what vital matter has already invented before him. “The biotechnical principle reigns everywhere we look. The decisive factor is necessity. What is needed is done, and the first adaptation is then improved where possible. Moreover, everything is done with the least expenditure of effort, in the most rational way. The system of T-beams that we use in our buildings is also applied in a similar way by plants.” [38]

Mosso also equated his structures with the organism: the thrust of his program text “Self-generation of Form and the New Ecology” was “for architecture as an organism”. [39] Beginning from 1964, he collaborated with the magazine Nuova Ecologia (New Ecology), which drew together the threads of structuralism, politics and environmental awareness. In 1970 Mosso and his wife Laura Castagno set up the Center for the Study of Environmental Cybernetics and Programmable Architecture at the Polytechnic University of Turin, where he developed an “eco-social” model of architecture, based on semiological, anthropological and ecological theories, calling for the involvement of ordinary people in the organization and management of space. [40] These principles were the basis of Mosso’s “non-authoritarian structural self-programming” and “non-object-based architecture” (the latter defined by Mosso when he presented his work at the 1978 Venice Architecture Biennale).

How does the idea of the organic come into connection with the idea of the programmable? In 1953 the editorial column of an issue of Architectural Forum magazine, in which Frank Lloyd Wright published an article on the language of organic architecture, asked the question: “But who is to say what is human?” [41] And in 1969, Manfredo Tafuri, in his article “Towards a Critique of Architectural Ideology”, asked: “What does it mean, on the ideological level, to liken the city to a natural object?” [42]

Mosso intertwined the organic paradigm with a rationalistic language, which had been compromised not only by Zevi, but also by other contemporary theorists, who offered a critique of techno-positivism that was to a large extent justified. For example, Tafuri linked all formalized artificial languages, be they sign systems or programming languages, to the scientific forecasting of the future and the use of “game theory”, and also to the development of capitalism, asserting that they contribute to the “plan of development” of capitalism. [43] Mosso emphasized that programming in his theory is not “game”, but “the self-determination of life and of each one’s personal abilities for the realization and conservation of the equilibrium man-environment-knowledge research-freedom-life-architecture”. [44]

How did the requirement for direct personal participation in “self-planning of the community” [45] and architectural planning coexist in Mosso’s program with the mediation of this participation by technology? Mosso was not a supporter of techno-positivism. As he declared in 1963: “The open wound torn by the industrial revolution in man has not yet healed.” According to Mosso, the new revolution, generated by the earlier one, had brought changes of a completely new level, being inspired not by the machine, but by the idea of organization and of a system. The idea of organization is what is crucial here, and it is contrasted with the absolute of form, which had previously concerned architects. Now, as Tafuri put it, the architectural object in its traditional understanding “has been completely dissolved” [46] in the task of industrial planning of the city. This distinction between plan and architectural object is most significant. The opening words of Mosso’s text about the new ecology show that the distinction was as important to Mosso as it was to Tafuri and that Mosso saw the concept of the plan as an unavoidable necessity in today’s world: “We must first understand that we all have to plan, not only a few of us. <…> It is simultaneously our duty to create those structural instruments of service which are indispensible for everyone in exercising their right and duty of planning ”. [47] Mosso renounced this function in his role as architect and delegated it to the computer, just as Tafuri renounced it and preferred to be a historian and critic. Mosso recognized that computational and programming methods had become a tool of exploitation, [48] but, realizing the impossibility of overthrowing them, he instrumentalized and intensified them, following the logic and, in fact, anticipating the project of accelerationism, similarly to Tafuri, who proposed that the shock of modern civilization should be “swallowed, absorbed and assimilated as today’s inevitability.” [49]

Translation: Ben Hooson