The concept of a hybrid (as well as its derivatives: hybridity, hybrid, hybridization) is used so widely today that it becomes synonymous with everything contemporary. Hybrid wars, hybrid regimes, hybrid cars. The word also takes on an evaluative meaning when hybridization is viewed as an effective weapon of progressive politics, disrupting endogamy, breaking down fixed identities and producing an infinite number of differences. Conservative critics, on the other hand, describe hybridization as a homogenizing practice that erases local traditions and conventions. So on one hand there is the ideology of fundamentalism, essentialism, purism and awesome invariants: purity, solidity, ineluctability. On the other, there are the processes of pidginization, creolization, glocalization and various transitional states (liminality, volatility, plasticity, fluidity). Toxic masculinity, white supremacism and identity politics are taking a beating from assemblages, prostheses and cyborgs.

In contemporary art, art hybridization is understood as something innovative or high-tech and is associated primarily with science art. Hybrid arts are a subculture that includes formalist practices of interactive design using high technologies with the prefixes “info”, “bio”, “nano”, “cogno”. Today, though, in the postmedium condition, any art is hybrid, because there is no longer a division into specific mediums (painting, sculpture, etc.), and the fundamentally interdisciplinary nature of art implies the inclusion of any research themes, openness to other areas knowledge and an invitation to experts from other fields to join in.

Perhaps the hybrid nature of art should be understood in a completely different way, putting the emphasis on its “non-artificial” character – a continuum between the natural and the cultural. By linking the concept of hybridity with its original biological meaning, we can reassess the very “artificiality”, “artistry” and “technicality” of art. Our start point will be a half-forgotten, almost curious exhibition project.

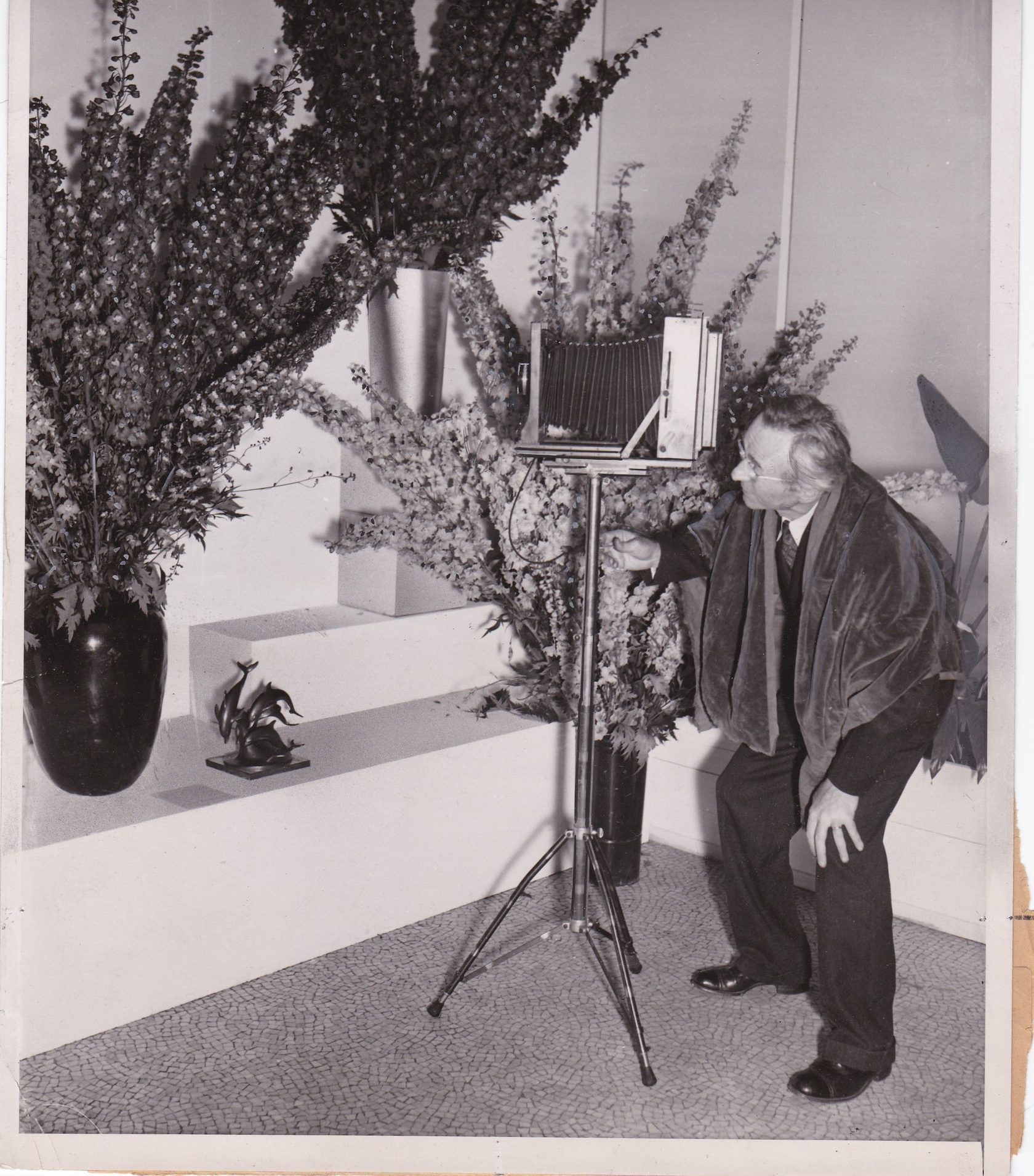

In 1936, MoMA presented some extraordinary “works” by Edward Steichen, one of the foremost modernist photographers. The exhibition, organized in two stages, displayed to the public varieties of delphiniums, which were the result of 26 years of work selecting and cross-breeding flowers on ten acres of land in Connecticut. In the first stage the public were shown “true blue or pure blue colors, and the fog and mist shades”, followed in the second stage by huge spike-shaped plants from one to two metres tall. The exhibition press release clarified: “To avoid confusion, it should be noted that the actual delphiniums will be shown in the Museum – not paintings or photographs of them. It will be a ‘personal appearance’ of the flowers themselves.”

At that time the public still viewed the activities of MoMA with much scepticism (especially after the Machine Art exhibition), and the Museum legitimized the non-traditional objects of its latest show by including various facts in the press release that testified to the status of these flowers in the history of culture. Reading the text, one might well suppose that the exhibition was the whim of an influential and museum-affiliated artist who was given the opportunity to present his hobby to the general public. Critics at the time and historians later paid little attention to the exhibition.

Today, however, in the history of art Delphiniums are regarded as the originator of the bio-art movement. The author of the bio-art anthology Signs of Life writes that Steichen “was the first modern artist to create new organisms through both traditional and artificial methods, to exhibit the organisms themselves in a museum, and to state that genetics is an art medium.” [1] It is unlikely, that Steichen – a commercial salon photographer – was seriously interested in the ontology of art at a theoretical level. For him flower selection was an occupation which, like photography, had to do with an aesthetic experience, an appeal to beauty.

The assessment by art historians of Steichen’s work as a dotted line linking Cubism with George Gessert’s later bio-art practices seems stretched and teleological. It is much more interesting to look at what such a project, implemented without design and little reflected in its time, can tell us about today’s understanding of art and its growing interest in the natural world. In this sense, we cannot treat the flowers simply as a “personal appearance”, as a modification of the readymade brought into the gallery-museum context. We need to pay attention to the actual process of their formation and materialization, of which Steichen himself said: “The science of heredity when applied to plant breeding, which has as its ultimate purpose the aesthetic appeal of beauty, is a creative art.” [2] Cleary this “creative art” is at the same time a “creative act” and what interests me is not so much a new medium, genre, species, technique or movement in art, but the fundamentally different approach, which Steichen proposes, to the creative act. It, as we will see, concerns three basic levels: art production (artistic method), the way of being of art (ontological status of the work) and its consumption (reception).

First of all, the application of hybridization to art production forces us to reconsider the concept of authorship. Poststructuralism demythologized the romantic figure of the author by asserting the unoriginal and self-citing nature of any work (the author, according to Roland Barters, is always just a “tissue of quotations”). [3] The new materialism, in the optics of which it is logical to describe Steichen, understands the artistic process as “co-collaboration”, that is, the joint action of artist and material. Modernist art was based on the principle of hylomorphism, i.e. the idea that passive material is shaped by an active form, that form being the discourse itself (art criticism, philosophy, history of art), which, through the artist as an abstract function, determines the distribution of the material (paint on canvas, metal in space, etc.).

Steichen offers another model, where the form is not just superimposed on material, forming their synthesis in a complete object, but, in the words of neo-materialists, “matter is as much responsible for the emergence of art as man.” [4] In other words, the substrate, the substance of art, is not simply used to achieve some or other artistic or conceptual goals. Matter is endowed with its own agency, its own will or goal-setting capacity. For example, for contemporary artists, the molecular forces of paint become important – the stratification of substances in themselves and as they are. So the artist is reduced to the role of partner or assistant of self-developing, pulsating matter, which has its own “interests” and “intentions” and is thus not reduced to an effect of discourse. [5] Such matter is emergent, self-organizing and generative. Steichen’s example is especially interesting, because the plant breeder works, not with inorganic, but with organic substance, penetrating into its very essence. [6] The artist is the helmsman of evolution.

Following these crude historical parallels with the modernists leads to the following conclusions about the avant-garde. The artist of the historical avant-garde tried to combine art and life, where life is understood as social reality (bios), because his or her work was intended to create a new utopian world. Steichen, however, tries to break down the boundaries between art and zoé – life itself. Posthumanists understand zoé as the dynamic, self-organizing structure of life itself – generative vitality. [7] It is interesting that Rosie Braidotti, who recognizes the intrinsic value of life (zoé) as such, calls this approach a “colossal hybridization of the species”, [8] where there is no significant difference between man and his natural “others”. The artist does not stand opposed to the flower. They are both part of the same creative act. Not only does Steichen hybridize delphiniums, but delphiniums hybridize him, their breeder.

Steichen’s interest in the bare factuality of the material lends him an affinity with contemporary artists. Steichen was not only fascinated by the technical and representative possibilities of photography; he was also interested in the chemical process of image production itself. Just as he produced huge numbers of negatives, most of which were never converted to positives, so he grew thousands of delphiniums in order to select the best examples. The production process here was like a struggle for survival, natural selection (or curatorial selective practice), and not a concentrated honing of the original. The artist was driven by a passion for selection – the practical side of theoretical genetics, which was at the peak of its development at that time. Selection had been a human capacity for millennia, but it was first carried out by scientific methods (and not blindly) in Steichen’s time. At that time (before Lysenkoism or before the complete discrediting of eugenics by fascism) it was perceived as a science of the future, comparable with the utopian pathos of the avant-garde, which swallowed not only bios, but also zoé.

Selection is based on the process of hybridization, whereby genotypes are chosen for their nutritious or aesthetic qualities, the preferred individuals are crossed with one another and those of their descendants which inherit all of the required features are in turn selected. So, generation by generation, the breeder brings the plant to the required state as expressed in its phenotype (i.e., the externally manifest features of the individual). Selection, therefore, in contrast with species isolation, is a matter of breaking down the boundaries of species – that “great bastion of stability,” as the biologist Ernst Mayr called it. Mayr gave a biological definition of species as “groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups.” [9] Today, in the light of new discoveries or the spread of hybrids and chimeras in biotechnological experiments, biologists and philosophers increasingly emphasize the limitations of this definition, although Mayr deserves credit for not absolutizing the nature of species boundaries.

Perhaps such a parallel will seem factitious, but if traditional contemporary art is based on the production of a certain type of art (the medium) or a specific individual (the work), in Steichen’s case, we find it hard to draw the boundary. Are his works only those delphiniums that were shown at MoMA in 1936? Or their seeds, which can still be bought today? Rather, hybridization can be understood as a process that emphasizes the conventionality of species differences. So he does not address a species, population or individual organism, but liberates life itself, the constant fluidity of the vital forces of nature (and of art). Artistic hybridization is a queer practice par excellence, a practice which highlights the very process of becoming rather than fixed identities. Such art and life is a constant movement of creating and erasing boundaries through the temporary accentuation of genetic mutations.

Hybridization not only changes the role of the artist (into an assistant to the material) and the status of art (into a constant becoming), but also makes the process of perception mutually directional. The philosopher Catherine Malabou believes that the paradigm of writing, which prevailed in the days of poststructuralism, is being replaced by the paradigm of plasticity – the ability to both acquire and give form. [10] Plasticity plays an important role in biology, particularly in the framework of a new evolutionary synthesis (sometimes misleadingly called “postmodernist”), where species are not considered in isolation from ecosystems. Suffice it to recall Charles Darwin, who poetically described the co-evolution of insects and flowers, where not only does the insect adapt to the shape of the flower, but the structure of the flower also uses ruses and devices in response to the requests and desires of the insect. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari would later describe this process as that of de- and reterritorialization: “The orchid deterritorializes by forming an image, a tracing of a wasp; but the wasp reterritorializes on that image. The wasp is nevertheless deterritorialized, becoming a piece in the orchid’s reproductive apparatus. But it reterritorializes the orchid by transporting its pollen.” [11]

The relationship of flowers and insects is a ménage-à-trois (for example, pistil, stamen and bee), but together with the artist they form a love rectangle or trapezoid, where all of the participants are equally involved in the process of receiving and passing on a form. And to understand this process, we must turn to an area that is (quite understandably) neglected by art theorists, namely, evolutionary or Darwinian aesthetics. This teaching is based not on the widely known idea of the survival of the fittest, but on the idea of sexual selection, i.e. differentiated access to partners (competition and choice of a partner of the opposite sex). The theory was developed by Darwin himself, who, trying to explain apparently redundant ornamentation on the bodies of animals, believed that sensual pleasure, attractiveness and subjective experience are also agents of selection.

This question remains a matter of controversy in evolutionary biology, where representatives of the two camps continue to disagree. The “adaptationist” interpretation insists that bodily ornamentation advertises and provides information about the useful qualities of the partner, while an alternative “arbitrary” model sees no benefit in the production of aesthetic attributes other than the popularity of the partner. The latter approach was developed by Darwin’s follower, Ronald Fisher, who described sexual selection as a positive feedback mechanism. For example, the more advantageous it is for a male to have a long tail, the more advantageous it is for a female to prefer just such males, and vice versa (in biology this principle is called “Fisherian runaway”). His radical follower, our contemporary Richard Prum, has pursued this line of thought, which also correlates with plasticity: partner preferences are genetically correlated with preferred features. In other words, “variation in desire and variation in the objects of desire will become correlated or enmeshed, entrained evolutionarily,” [12] beauty and the observer co-evolve. Aesthetic attractiveness makes the body free in its sexuality: “birds are beautiful,” Prum writes, “because they are beautiful to themselves.” [13]

Feminist critiques of Darwinism, however, go much further in defending Darwin against reductionism. For example, Elizabeth Grosz questions the raison d’être of sexual selection and emphasizes its irrational character, expressed in an unbridled intensification of colours and shapes, extravagance, excessive sensuality and an appeal to sexuality rather than simple reproduction. She tries in this way to separate natural from sexual selection (the second is usually considered a subspecies of the first). In particular, she writes: “Sexual selection may be understood as the queering of natural selection, that is, the rendering of any biological norms, ideals of fitness, strange, incalculable, excessive.” [14] Moreover, sexual selection expands the world of the living into ”the nonfunctional, the redundant, the artistic.” [15] And here we are again reminded of Steichen’s Delphiniums, which only intensify the already excessive beauty of this flower. But how does this leap from nature to culture happen? Why does a person become an addressee of someone else’s sexual selection? How does he or she get drawn into this “co-evolutionary dance”?

Describing the attractiveness of flowers (including delphiniums) and their ability to come to life in our imagination, Elaine Skerry highlighted their various characteristics: the size that allows them to freely penetrate our consciousness, the bowls that correspond to the curve of our eyes, the possibility of their localization by vision, the transparency of their substance, etc. [16] However, this says little about plasticity. Without extrapolating biological principles to social ones, I would propose that an even more complex process is at work in Steichen’s love rectangle or trapezoid, where not only does the artist subordinate the flower to his aesthetic needs, but the flowers themselves determine the artist’s sensory experience. The reception and consumption of art cannot be a one-way process, but are subject to positive or negative feedback. There is no need to go far for an example: in Russia flowers of Northern European selection (the so-called “the new perennials”) – calmer, more austere and vegetative – are gradually supplanting the gaudy and bright flower varieties that were popular in Soviet times. We can easily trace how flowers steer our taste. Could it be that our taste, our aesthetic judgment, is also a hybrid?

Following in the steps of Steichen’s experiments, I have tried to retroactively comprehend what hybridization as a creative act might be today. However, despite all that has been said above, I am not sure that hybridity in itself is of indubitable value. We know from evolutionary theory that mixing does not always lead to diversity, and the endemics so dear to us are a product of the isolation of species (“Splendid Isolation” is the title of a book about the remarkable mammals of South America), [17] because “isolating mechanisms” between species preserve originality and authenticity. In a similar vein, some left-wing philosophers say that by altogether abandoning identity politics and insisting on the fluidity of categories, we make ourselves vulnerable to traditionalism. For instance, if you consider yourself fluid, what prevents you from abandoning your essence and accepting a fixed norm? Hybridity also comes in for criticism as a product that masks the policy of global imperialism, because it is based on the exclusion of “others”: old age, uncommunicativeness, pain, i.e., non-hybridity itself. [18]

Hybridity and its dark double, non-hybridity, are in equal measure social constructs. Perhaps everything around us is equally hybrid. However, the hybridization procedure is not just a progressive trope, but also a subversive procedure. Hybridization, unlike many other analogous concepts, is associated with biology, i.e., with something natural and inherent to nature itself, but at the same time is also a cultural practice of selection, and for this reason it undermines naturalness as such. Unlike concepts that naturalize, that represent human history as something natural, it naturalizes unnaturalness itself. The unnatural seems natural. As Steichen shows us, the boundaries between art and nature are highly arbitrary. Life imitates art. Art imitates life.

Translation: Ben Hooson

1. Ethnography is generally understood to be the field study of social and cultural groups. And ethnology compares the results obtained by ethnographers in order to arrive at certain generalisations about human nature. The key feature of ethnology understood in this way is the comparative method, which aspires to a certain theoretical meta-level with respect to ethnography, since ethnography is exclusively concerned with observation of the facts of specific cultures.

The French tradition preferred to call itself ethnological. Starting at least from Émile Durkheim in the second half of the 19th century, French researchers focused on decoding cultural reality. In the process, the border between sociology and ethnology was blurred, i.e., the study of cultures was understood primarily as the study of “social facts” (Durkheim’s term). While the Anglo-Saxon tradition continued to describe various ethnographic and cultural formations as values that have an indubitably unitary nature, the French sought to perceive them as semantic sign systems. The French approach revealed the social construction of cultures and opened the way for full cultural relativism, where different cultures are merely different systems of signs and conventions. James Clifford expressed this by saying that the French ethnological tradition is highly sensitive to the over-determination of total social facts.

Paradoxically, the belief in complete semantic cultural relativism gave rise to a search for cultural, or more ontologically profound, invariants — universals that unite people beyond the confines of constructed symbolic cultural systems. So French ethnology produced generalisations about human nature, justifying its more theoretical character compared with ethnography. And if one believes a “Cartesian” tendency, a rational dissection of the world, to be the distinguishing feature of French thought, this dual process of deconstructing cultural and social facts and then searching for humanistic universals (what are left after the semantic “dissection”), is a very clear manifestation of that thought.

In regard to museums, these issues were exercised most clearly in the encounter with objects of other cultures. It could be said all of the challenges described above originate from a certain perplexity in the presence of an other object, an object that denotes a world outlook and life practice that are radically different from those accepted in the society, to which the ethnologist belongs. That encounter spurs research to find answers to certain questions: why is this object other and what exactly is other about it; to what practices does its other form lead; and, finally, is it really so completely other, or does the effect, which it produces on us, in fact depend on something we have in common with it?

French colonialism brought home a generous supply of objects that posed these questions, and private collections and museums became places of encounter with the Other.

2. From 1878, ethnographic objects were amassed in the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris (the Troca as it was familiarly known), a building in outlandish Byzantine-Moorish style. The collection was poorly organised and presented, resembling a repository of strange things rather than a museum. By the turn of the 20th century, what visitors found here was a dust-covered miscellany of unlabelled objects in an unheated and inadequately lit space. The impression, according to contemporary accounts, was mystical.

From the 1910s the Troca suddenly became a place of pilgrimage for innovative artists. It was where, in 1907, Picasso discovered African art. What the Troca and private collections of ethnographic objects offered to Picassos and other future heavyweights of 20th century art were examples of an other aesthetic, which they could set against the European aesthetic.

This felt like the birth of the Contemporaneity, in opposition to the linear, narrative, Western-centred Modernism (the logic of the modern period). Proto-postmodernist, or proto-contemporary views were well represented among the international avant-garde, which was gathered in France at that time, notably among the surrealists and some ethnologists. The ideologues of left-wing Eurasianism, a trend in Russian émigré thought, also had close ties with this environment. [2] In 1928, for example, the émigré composer Vladimir Dukelsky (Vernon Duke) published a programme article in the Russian-language Paris newspaper Eurasia entitled “Modernism against the Contemporaneity”, in which he championed the Contemporaneity in opposition to Modernism. The Contemporaneity was understood by Dukelsky and those of like mind as the substitution of a geographical for a historical understanding of the World, and of a spatial, egalitarian understanding for one that was linear and progressive (and thereby repressive). The avant-gardists sought real alternatives to the indulgent orientalism of the 19th century and made cultural relativism possible. By an irony of fate, the authors of the Contemporaneity project — rebels against Modernism — were later dubbed “classics of Modernism”, and their logic was called the “modernist cultural attitude”.

the aim of the eco-museum was to involve people in the process of museum creation, bringing them together around the project, making them actors in and users of their heritage, creating a community database, and thereby initiating a discussion within the community about self-reflective knowledge.

By the mid-1920s, the Troca was a fashionable place and the Contemporaneity project — or, according to accepted terminology, the “modernist cultural attitude” – was in full flood. In 1925−1926, the Institut d’ethnologie was opened in Paris, the manifesto of Surrealism was published, Josephine Baker played her first season at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées and the Eurasian seminar “Russia and Europe” was held next to the Troca. The neighbourhood of these last two is striking, since their missions were similar: they radically questioned the norms of European, Western culture and offered alternatives from other geographical contexts.

The deep relationship between Surrealism and the emerging modernist ethnography has been described in some detail by James Clifford. [3] Ethnology [4] provided a science-based levelling of cultural norms, which entailed a reset of all generally accepted cultural categories (“beautiful”, “ugly”, “sophisticated”, “savage”, “music”, “art”, etc.). Ethnology and the other objects, which it provided, were the wild card or joker in the pack — the card that can take on any value. In the 1920s the young generation of French scholars (Michel Leiris, Marcel Griaule, Georges Bataille, Alfred Métraux, André Schaeffner, Georges Henri Rivière, Robert Desnos) divided their interest between ethnology, poetry and surrealist art. All of them attended the ethnology lectures of Marcel Mauss, who was the link between the sociological ethnology of his uncle and teacher, Émile Durkheim, and the new generation, which shaped modernist ethnology. Mauss’ lectures used a “surrealist” technique: collating and comparing data, conclusions and facts from different contexts. This often led to inconsistencies, which Mauss did not seek to dissolve within the framework of a single narrative or point of view. He is credited with the adage, “Taboos are made in order to be broken”, to which Bataille’s later theory of transgression is a close correlate.

The long friendship between Bataille and the field ethnologist Alfred Métraux symbolises this single field of ethnology and surrealism in the 1920s, and the publication of Documents magazine in 1929−1930, under the editorship of Georges Bataille, can be viewed as the joint achievement of the two movements. The magazine combined texts by ethnographers, semantic analyses of contemporary French culture (including mass culture, such as the Fantômas books), and essays on contemporary artists. For example, the Polish-Austrian art historian Józef Strzygowski in his article “‘Recherches sur l’art plastique’ et ‘Histoire de l’art'” http://redmuseum.church/smirnov-objects-in-diaspora#rec172587079[5] called for linear historical narratives in the study of art to be replaced by plastic formal analysis, for a geographical instead of a chronological view of the World, using maps instead of history as a measure, and filling gaps with monuments (plastic art research instead of art history). In an illustration to the text, he visually compared the plans of three churches: Armenian, German and French. The comparison shows that they are all similar and reproduce an initial structure, which is seen in it most “pure” form in the (oldest) Armenian church. Strzygowski’s conclusion, overturning established cultural hierarchies, was that “Rome is from the East”.

In the second issue of Documents in 1929, Carl Einstein, poet, art theorist and author of the important article “La plastique nègre” (1915), offered an ethnological study of the contemporary artist, André Masson. The study deserves to be called ethnological because it argues that Masson used psychological archaism in his paintings and turned to mythological formations akin to totemic identification for the creation of his artistic forms.

This method of searching for mythological formations and an ontological universal archaic explains the interest of Documents in parts of the body. In two essays on civilisation and the eye, in the fourth issue of 1929, Michel Leiris writes that all civilisation is a thin film on a sea of instincts. When various cultural conventions are laid aside and cultures are deconstructed, what remains is a “dry residue”, outside the bounds of civilisation, such as the eye or the big toe.

It is not surprising that the fictional idol of French popular culture, Fantômas — a fierce criminal and sociopath, a character without identity who dons various masks to commit crimes against his own culture — was among the favourite topics of Documents. His cruelty and sociopathic attitude towards his compatriots matched the “cruel” analysis and dismemberment of their own cultural order, which the surrealists and ethnologists undertook in their transgressive role as cultural “criminals” or “terrorists”.

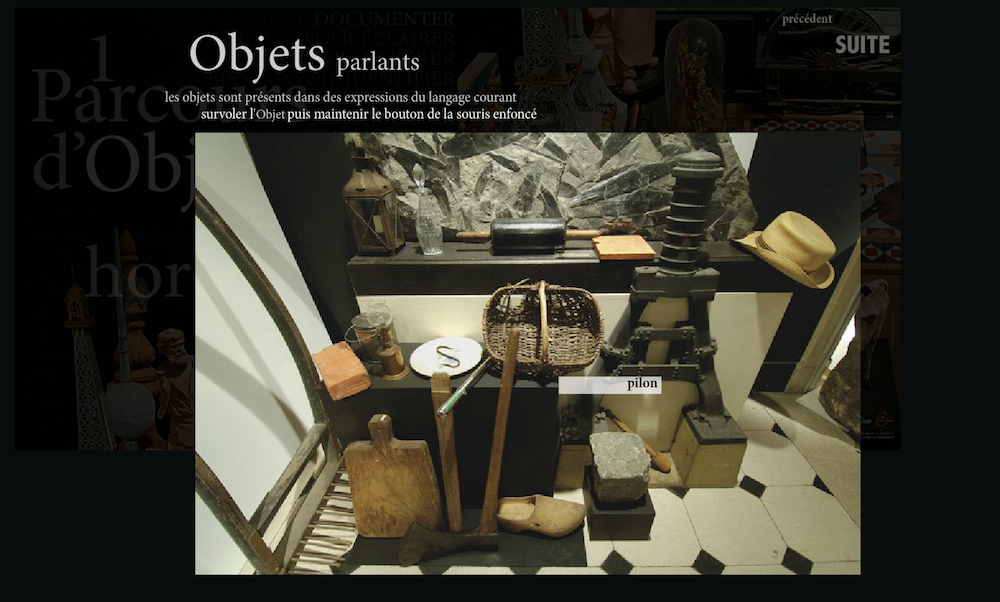

Documents was compiled on a collage principle and was, in essence, a museum that subverted and disrupted cultural standards. It was a playful collection of images, samples, objects, texts and signatures, a semiotic museum, which, in the words of James Clifford, did not strive for cohesion, but reassembled and transcoded culture through collage. Any divisions between “high” and “low” were discarded, everything was deemed worthy of collection and exhibition, so the only task was that of classification and interpretation. The combinations on the pages of Documents are a question analogous to that, which is posed by an ethnographical exhibition. By combining materials and images on the pages of the magazine, its authors carried out the same function as modernist ethnologists working in the museum.

The cultural climate of the 1920s gave the Trocadéro a new lease of life in the later part of the decade. In 1928, Paul Rivet, one of the founders of the Institut d’ethnologie, became director of the Museum. He involved the young museologist, Georges Henri Rivière, in his work at the Trocadéro. The two men, each of them key figures in French ethnological museology, immediately set to work reorganising the collection.

Paris was seized by a craze for everything that was “other”. Wealthy collectors begin to patronise the Troca. Star-studded fashion shows and boxing tournaments were held to raise money for new expeditions such as the Dakar-Djibouti Mission, the main purpose of which was to collect new ethnographical exhibits. However, the single undifferentiated field of ethnology and Surrealism, with their shared orientation towards semantic critique of their own culture, began to disintegrate. The work of corrosive, i.e., “questioning”, deconstructing analysis of reality had been completed, and each of the two spheres began to acquire its own definite outlines. Surrealism soon had its own institutions and specialised print media, in which the new art was associated with the internal, visionary approach of the Breton mainstream faction, from where it is not far to the old, conservative figure of the artist-genius who creates worlds from his inner experience. Ethnology, for its part, affirmed cultural relativism and went in search of universals of human nature.

3. The transformation of the Trocadéro into the Musée de l’homme (“Museum of Man”) has to be understood in the political context of France in the 1920s and 1930s. Paul Rivet, the founder of the Musée de l’homme, was a convinced socialist and his new museum sent a political message. A left-wing left coalition consisting of the French section of the Socialist Workers International (SFIO) and representatives of the Radical Party has been in power in the country since 1924. Despite its “radical” name, the party occupied liberal-progressive positions: its members could only be considered radicals in the context of an exclusively bourgeois and conservative political environment and in the absence of strong socialist and communist parties. The Radical Party was the oldest political party in France, and its position was analogous to that of the Russian Narodniks (“People’s Party”) or of Evgeny Bazarov (fictional hero of Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons) in the conservative, bourgeois environment of the late 19th century. At that time the French Radical Party had been truly radical, but by the 1920s it had shifted to a centrist position, defending market-oriented freedoms.

By the mid-1930s, leftist intellectuals had become acutely aware of the dangers of fascism. In 1934, right-wing street demonstrations led to the break-up of the left coalition government, and anti-fascist intellectuals began to mobilise against the perceived threat. In the same year Rivet was among the founders of the Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes (“Vigilance Committee of Antifascist Intellectuals”, CVIA), which brought together representatives of the French section of the Workers International, the Radical Party and the Communists in an unlikely alliance. The CVIA can be seen as the prototype of the Popular Front government, which was formed in 1936 from representatives of the same three main leftist parties. The period of office of this government (1936−1938) was the high tide of left-wing ideology in France, and it was during these years that the Musée de l’homme was opened.

Universal humanism, declared as the programme of the Musée de l’homme, was the embodiment of the CVIA’s international humanism, a manifesto of anti-fascist socialist universalism. The Museum asserted the primacy of universal values over cultural differences (prized by the fascists and by right-wing ideologies in general), championing the mind against the aura and magic of the object. The creators of the Museum believed that the divisions of political geography are just as arbitrary as cultural divisions within humanity.

The cosmopolitanism of the Musée de l’homme was the dialectical heir of the collapse of hierarchies in the surrealist ethnography of the 1920s. After the work of total cultural relativisation has been carried out, no single cultural whole, including that of one’s own culture, could be taken as foundational. Under the growing shadow of fascism, the Museum postulated a single humanity, emphasising what was in common rather than what was different.

What was left after the fragmentation of the 1920s? A considerable amount was left: the shared biological evolution of humankind, the archaeological remains of primeval history and the assertion of the equal value and equal rights of today’s cultural alternatives. The museum no longer executed corrosive analysis of the cultural codes of reality. French ethnology abstracted from different and equal symbolic constructions of cultures to obtain the integral humanism of Mauss and Rivet and, later, the human spirit of Claude Lévi-Strauss.

This was, without a doubt, a progressive attitude, and the Musée de l’homme became a symbol of the ideas of the Popular Front in the pan-European socio-political context of those years. The old Byzantine-Moorish Trocadéro building was demolished and replaced by the modernist Palais de Chaillot as part of large-scale reformatting of the architectural landscape in central Paris and preparations for the World Exhibition of 1937. Just as modernist ethnology abstracted from cultural specifics and differences, beloved of Orientalism and emphasised by the political right, the new palace used only the “pure”, abstract forms that remained after the reduction of the historical stylisations and architectural historicisms of the 19th century (the “Moorish” decoration and “Byzantine” roof of the old Trocadéro). Abstraction also meant the search for universal human foundations and the rejection of any cultural hegemony.

The main practical consequence of such an ideology for actual museum exhibitions was much broader contextualization: the exhibits were shown with titles and explanations, placed in the context of their function, and distanced from the viewer in glass cabinets. Objects of “primordial art” were radically de-aestheticised and considered as functional and symbolic components of specific cultures. The Musée de l’homme preserved geographical divisions, including the creation in 1937 of a France department, headed by Georges Henri Rivière. The Museum’s informational and scientific component was much increased, building a clear and progressive narrative into its exhibition. It differed from the pre-surrealist, orientalist narrative by the abolition of any hierarchy or “insuperable” cultural differences and emphasis on what people from different cultures and races have in common. [6] The ethnological museum has ceased to be a collection of titillating objects. Instead, it offered clarification and made the other accessible and understandable through a detailed explanation and the creation of a universal semantic field.

4. Museology experienced a crisis in the 1970s. Large, universal narratives were now felt as repressive. It became clear that such narratives leave their source and the projections of their would-be universalism — the discursive structures of the particular society that formulated such universalism — invisible, even as the specifics of that society’s “logos” [7] remain scattered throughout the narrative and expositional structure, and even if a distancing from that society is postulated by the structure, as in the department of France at the Musée de l’homme. At issue were the invisible epistemological and hermeneutic structures that organise knowledge itself.

It was understood that the museum should be much more connected with the social life of the local community and play a greater role for that community than could be played by a brute collection of objects and repository of knowledge. In the new museology, museums were to be the servants of specific communities. In France, this need gave rise to the concept of eco-museums, developed principally by three museologists: the same Georges Henri Rivière and two representatives of the younger generation, André Desvallées and Hugues de Varine.

In 1969, the France section, Rivière’s brainchild, moved from the Musée de l’homme to a separate building where it became the Musée national des arts et traditions populaires (“Museum of Folk Arts and Traditions”, MNATP). Ten years earlier Rivière, then also director of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), had hired André Desvallées to run the museology department of the France section. Desvallées gained renown as a methodologist in the sphere of folk museums for his work in the 1960−1970s in the France section and at the MNATP, which set standards as an advanced museum institution.

In addition to its permanent exhibition the MNATP had three galleries for temporary exhibitions, which Desvallées also worked on. The main practical principles of his museology were emphasis on the “vernacular” [8] and context dependence. Influenced by Duncan Cameron, [9] Desvallées came to understand the museum exhibition as a communicative system with visuality and spatiality as the key features of its medium. He developed the theory of “expography”, or the technique of “writing” an exhibition as a text. According to Desvallées, this process is based on research and its ultimate aim is to establish communication with the public and convey to it the message intended by the museographer.

The impact of Desvallées on formation of the eco-museum as an institution was very great: both conceptually, by developing and putting into practice the principles of regional folk museums, and also in terms of organisation. [10] The term “eco-museum” was proposed by Hugues de Varine at the 11th ICOM conference in 1971. It was intended that eco-museums would be the main vehicles of new principles in museology. They would serve as mirrors for the local community, both as internal mirrors, explaining to people the territory, which they themselves inhabited, and their connection with the generations who lived there before, and also as external mirrors for tourists and visitors. The key principles were the social aspect of the museum and emphasis on the tangible and intangible heritage of the community, in which the museum is created and whose identity it reflects. The aim of the eco-museum was to involve people in the process of museum creation, bringing them together around the project, making them actors in and users of their heritage, creating a community database, and thereby initiating a discussion within the community about self-reflective knowledge.

The structuralist realisation that any knowledge and narrative is a sign and part of an identity has led to the requirement that museums should be constructed by communities themselves. So it is to be left to others themselves to care for their heritage and objects. French museology has, in this, largely coincided with museology in the Anglo-Saxon countries, which began at about the same time to engage the members of First Nations and Indigineus cultures in the creation of museums representing their cultures. These practices correlate closely with the “chorological” projects of local history museums, which were developed by the Russian liberal intelligentsia in the 1910s and the first half of the 1920s. The concept of chorology (from the Greek “khōros”, plural “khōroi”, meaning “place” or “space”) is based on the idea that the space of the Earth is made up of specific “khōroi” each of which is a separate, distinctive, complex space. Chorological local history highlighted, described and identified such “khōroi” and chorological museology sought to represent them in regional and local museums. The Moscow students of Dmitry Anuchin’s school (representatives of the new geography) were particularly committed to this approach. The most notable among them was Vladimir Bogdanov, who created the Museum of the Central Industrial Region in the Soviet capital in the 1920s. However, chorological local history in Russia was subsequently reformatted to fit the Soviet Marxist mould.

In Western European the 1970s saw a return of cultural relativism associated with local identity (the same occurred at the same time in the unofficial sphere in the USSR). In French museology, this process was a dialectical development of the socially engaged project of the Musée de l’homme. But the order of the day was no longer to affirm universal human values, which were now passed over in silence, but to cultivate local communities. In the concept of the eco-museum, the progressive pathos of French ethnological humanism was combined with a post-modern deconstruction of universal narratives.

But, despite the application of new principles in community museums and particularly in various regional eco-museums, the principal ethnological museums remained as they had been, their entire exhibitions embodying knowledge structures that were already perceived as repressive. In the 1980s, the whole of ethnographic science was perceived as a way of creating a dominant narrative. And while Anglo-Saxon science traditionally recognised differences, emphasising the struggle of minority cultures for their rights, French museology insisted on universalism, egalitarianism and the equality of races and cultures. So French ethnological museums faced a paradoxical task: to dismantle universal narratives, while at the same time insisting on certain unchallengeable and specifically “French” universal values, such as tolerance and the equality of cultures. [11]

Under the conditions of (neo-)liberalism and a corresponding upsurge in the role of collectors in all spheres related to art, a solution was found in the “subtraction” of the repressive scientific narrative and the re-aestheticisation of ethnographic objects. In France, this process is associated with the project of Jacques Chirac (President of France from 1995 to 2007) to create the Musée du quai Branly, a vast new ethnographic museum on the banks of the Seine in Paris.

5. Chirac had been an enthusiast of eastern cultures from an early age and in 1992, as Mayor of Paris, he refused to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage, citing the crimes against other cultures, which followed upon that event. In the 1990s, during a vacation in Mauritius, Chirac met Jacques Kerchache, a collector and amateur ethnographer. A couple of years earlier, Kerchache had published a book, African Art, where he argued that, apart from, and more importantly than their ethnological value, objects of “primitive” or “first” art possess high artistic value and that these objects should be viewed through the prism of aesthetics. The story is that Kerchache was emboldened to introduce himself to the Paris Mayor after spotting his book in a photo of Chirac’s office, among the books and papers on the Mayor’s desk. Chirac told the collector that he had indeed read the book several times and was very glad to meet the author. An alliance was forged between politician and collector, which would have momentous consequences for ethnological museums in the French capital.

Chirac considered art and ethnology to be two completely different disciplines, as he emphasised in a landmark speech given in 1995 at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle (Natural History Museum) in Paris. He and Kerchache supported the concept of “arts premiers” (“first arts”), which was anathema to the social and contextual thinking of the ethnologists of the Musée de l’homme. For them, the term “first arts” represented a return of obscurantism, since it was a descendant (albeit less harsh on the ear) of the term “primordial arts”, beloved of the Gaullist Minister of Culture, André Malraux. It should be noted, however, that a decade before Malraux gave currency to “primordial arts”, the structuralist Lévi-Strauss had taken the “human spirit” as the building block of his universal theories. The concept of “first arts” can be seen as the triumphant return of universalism to French museology, but accompanied by a re-aestheticisation of the object, which the “priests of contextualisation” found unacceptable.

Chirac and Kerchache initially wanted to reform the Musée de l’homme, but, faced with powerful opposition from its curators, they decided that it would be easier to build a new museum. In 2000 a department specialised in the “best” works of first art was created at the Pavillion des Sessions (part of the Musée du Louvre), under the management of Kerchache, and in 2006 the Paris public was presented with the highly ambitious Musée du quai Branly. The collection of the new museum consisted of works from the ethnology laboratory of the Musée de l’homme and from the Musée national des arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie (National Museum of the Arts of Africa and Oceania), enriched by 10,000 objects acquired from museums and collections, over which Kerchache had rights.

The two institutional collections, which the new museum brought together, were of quite different natures. The Museum of Africa and Oceania had been established by André Malraux in 1961 as a museum of French overseas possessions on the basis of the colonial exhibition of 1931 and was an aesthetically oriented collection. The ethnological collection of the Musée de l’homme was a highly contextualized collection, which “abstracted from” the aesthetic properties of objects.

a diaspora of forms, objects in diaspora, are, in a sense, the ideal republican model (if, by “republican”, we mean the new political mainstream, combining economic neoliberalism with cultural conservatism).

Choosing a name for the new institution presented special challenges. Chirac and Kerchache wanted to affirm cultural diversity through the universal dominance of art, but some new museological concept had to be found to express this, which would not scandalise the scientific community of museologists. Names such as “Museum of the First Arts” and “Museum of Man, the Arts and Civilisation” were considered, but the first introduced regressive terminology and hinted at a connection with the art market, while the second unjustifiably separated art from civilisation and put them in apposition. So it was decided to name the new institution after its address: Musée du quai Branly (“Museum on Branly Embankment”). Later, the name of the Museum’s creator, Jacques Chirac, was added to the title. Oddly enough, the final version successfully reflects the voluntaristic and subjective nature of the institution in the new (neo-)liberal context.

The declared goal of the Museum was cultural diversity and its creators explicitly presented it as post-colonial. Kerchache wrote in his manifesto: “Masterpieces of the entire world are born free and equal”. However, the noble task of putting the cultural diversity of the World on display was represented exclusively through art practices that were proclaimed as universal. The architect Jean Nouvel built a “temple of objects”, where the visitor, after passing through the “sacred garden” of landscape architect Gilles Clément, found him/herself in a hugely immersive space without reference points.

Scandals soon erupted around the new Museum. The architecture critic of The New York Times Michael Kimmelman described it as a “spooky jungle, […] briefly thrilling as spectacle, but brow-slappingly wrongheaded”. [12] The curator of the Asian collection, Christine Hemmet, showed Kimmelman the back of a Vietnamese scarecrow, on which falling American bombs had been painted, and said that she had wanted to install a mirror to show this to the viewer, but was not permitted to do so. The director of the Museum, referring to the earlier generation of socially oriented museologists, told Kimmelman, that “the priests of contextualization are poor museographers”.

A conflict broke out between the ethnological laboratory of the Musée de l’homme, on the one hand, and Chirac and Kerchache, on the other. Bernard Dupaigne, the head of the laboratory, published a book, Le scandale des arts premiers: la véritable histoire du musée du quai Branly (“The scandal of the first arts. The true story of the Museum on the Branly Embankment”), [13] where he called the new museum “pharaonic” and wrote that the staff of the Musée de l’homme have nothing against the exhibition of non-Western objects as art, but are against the term “first art”, because it denies that the objects have a history or underwent changes, and treats them as “original, primary art”, which leads to a “new obscurantism”.

The museologist Alexandra Martin called the new institution the “Museum of Others”, arguing that others are represented there as others for Europe, without a past or a living present. [14] Bernice Murphy, head of the ICOM Ethics Committee, dubbed the new principles, manifested by the Musée du quai Branly, “regressive museology”, and the Portuguese museologist, Nélia Dias, suggested that what had happened at the museum was a “double erasure”, rubbing out both France’s colonial past and the history of the collections. [15] Dias suggested that the museum had an implied political brief: it was opened at a time when France was experiencing problems with migrants, and, unable to solve problems with real people, the country had delegated this task to the museum. The mission of the Musée du quai Branly, according to Dias, was to exculpate society for its failure in dealing with the people and cultures whose objects are kept in museums dedicated to cultural diversity, so that equality in the field of art goes hand in hand with inequality in society. [16]

Ethnologists who kept faith with progressivist traditions perceived Chirac and Kerchache as the epitome of the Gaullist art establishment. Journalists alleged that Chirac (once nicknamed “the Bulldozer” by his political ally, Georges Pompidou) had pushed through his museum project amid nepotism, corruption and exorbitant pricing, ignoring the opinion of the scientific community and focusing only on the opinion of Kerchache, whom Bernard Dupaigne referred to as a “trader” and even a “looter”. [17]

All in all, the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (to give it its full name) was seen as an attempt to create a new type of institution reflecting neoliberal ideology. Drawing on postcolonial theory, the museum proclaims cultural differences, as if proclaiming as a new kind of universalism. Kimmelman, in his damning review, cited Chirac’s declaration at the Museum’s opening that “there is no hierarchy among the arts just as there is no hierarchy among peoples”, and made the powerful retort: “No hierarchy, except that at the Pompidou Centre [the best-known Paris collection of modern and contemporary art] you find Western artists like Picasso and Pollock; at Branly, it’s Eskimos, Cameroonians and Moroccans. No hierarchy, but no commonality either. Separate but equal.” [18] Indeed, this artificial division between human cultures expresses the core of neoliberal conservatism, which states: “To each his own.” Cultural divisions correspond to economic divisions, which are beneficial and desirable for the market and for the centre-right political parties that dominate the world today, notably the republican parties in France and the United States. Pluralistic universalism and assimilative universalism are quite different things.

In the new paradigm, the world is divided between, on the one hand, those who have identity and produce cultural diversity, “nailed” to their places of residence and, as a rule, poor living conditions, and, on the other hand, the few who are able to “understand” them, i.e., to consume their culture, have access to it, play with identities, proclaim universalism and have an increased appetite for everything that is other. This situation sets the stage for an interesting piece of legerdemain in respect of objects. As Octave Debary and Mélanie Roustan have written in a study, the visual experience of a visitor to the Branly museum is that of a meeting with the Other and with the absence of the Other. [19] Others have disappeared, they are absent, there are no accompanying texts to explain anything about them, but their objects remain, and this unexpectedly prompts a question on the part of the visitor: why are we seeing these cultures here, what happened to them?

Objects without their creators generate a diaspora of things, or, to use John Peffer’s term, “objects in diaspora”. [20] These objects seem to have achieved something that was not vouchsafed to their creators: they have emigrated and fitted into the Western context. The creators of these objects — certain tribes and societies — no longer exist, but the objects taken from them, which came to Europe through processes of coercive control, are here, representing their cultures. It is clear that all the theories of the last 30 years, which lend great importance and independent life to objects, are connected with the new political and economic conglomerate. A diaspora of forms, objects in diaspora, are, in a sense, the ideal republican model (if, by “republican”, we mean the new political mainstream, combining economic neoliberalism with cultural conservatism). This model brings along with it a speculative philosophy that endows things with a special agency, freeportism as an artistic style and ideology, [21] an enhanced role for collectors and, to a large extent, a postcolonial theory, which proclaims difference and is neutral towards separation.

The key question in the new situation is: do the intellectual ideologies and concepts, which have been described, offer any new progressive opportunities? The crisis of ethnographic representation in the 1980s was clear to see. A full return to the principles of contextual, “correct”, socially responsible museology is no longer possible. One sign of this is the fact that the Musée du quai Branly has proved very popular with the general public. Ethnological museology in France has passed through a series of dialectical transformations: from the unified experience of science and art (the “surprising objects” of the Trocadéro Museum) to the stripping away of the aesthetic and private (the ethnographic humanism of the Musée de l’homme), then to the removal of the universal and the return of differences, but maintaining a social mission and still excluding aestheticism (eco-museums), and finally to the return of aestheticism at the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, whereby Paris has restored one aspect of the old Trocadéro.

Marking the opening of the Musée de l’homme in the 1930s, Michel Leiris praised the new institution as progressive, but paid tribute to the old Troca for its avoidance of didacticism and strict boundaries, a loss which he sought to remedy in the Collège de Sociologie, [22] which retained the spirit of surrealist ethnography as radical cultural criticism. Today in Paris there is a partial recreation of the Troca, in the Chirac Museum, and there is the Musée de l’homme, but neither of them achieves an integrated, critical attitude towards their own culture. The only alternative offered by Bernard Dupaigne and many other critics of the Chirac Museum is a return to contextualised exhibitions, which, let us remember, were also once seen as repressive. The Chirac Museum does not attempt cultural criticism in its permanent exhibition, but its parallel programme raises many questions and perhaps shows a way of escape from disciplinary frameworks, contextualisation and aesthetics. Interdisciplinarity and cross-culturalism are, undoubtedly, among the products of the described “republican” conglomerate. [23] It may be that the new political economy has given birth to a new museum form, a form that cannot be described using exclusively old definitions without omitting precisely what is new about it.

But this does not stop us criticising the political and economic forces and processes that generated and maintain the Chirac Museum. We might propose a new concept, that of “republican museology”, the essential features of which have been described above, including a special focus on the object, as expressed most vividly at the Chirac Museum. This museology combines progressive and conservative features, postulating cultural diversity, but depriving the diversity of anything rational in common besides its possibility to produce affect in viewers. It mirrors the transformation, undergone by the republican ideal itself. Today this ideal is more likely to be the preserve of the centre-right, where market freedoms make an alliance with cultural diversity, underwritten by a conservative and post-colonial agenda, and market universalism is often left hidden. Real social problems to do with people are transferred onto objects, which are endowed with fetishistic, auraistic and subjective properties in a “total market” context. This is accompanied, in the intellectual sphere, by various speculative theories and, in the field of art, by the special role accorded to collectors and the increased importance now given to the materiality of works and practices of working with objects.

What we are faced with, overall, is the traditional problematic of French ethnology, with the issue of an other object at its centre. Hence the scale and intensity of the public debate aroused by the recent reformatting of Paris’ ethnological museums.

Translation: Ben Hooson

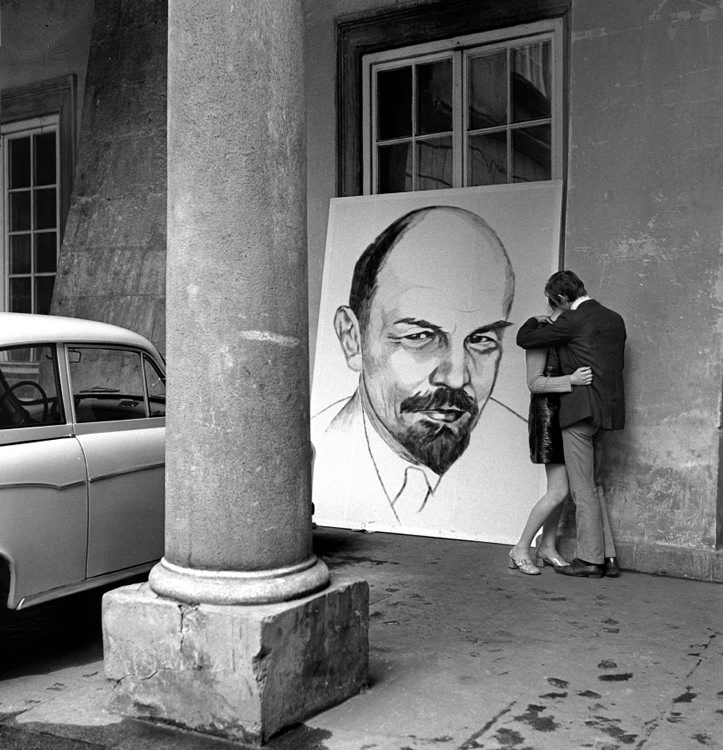

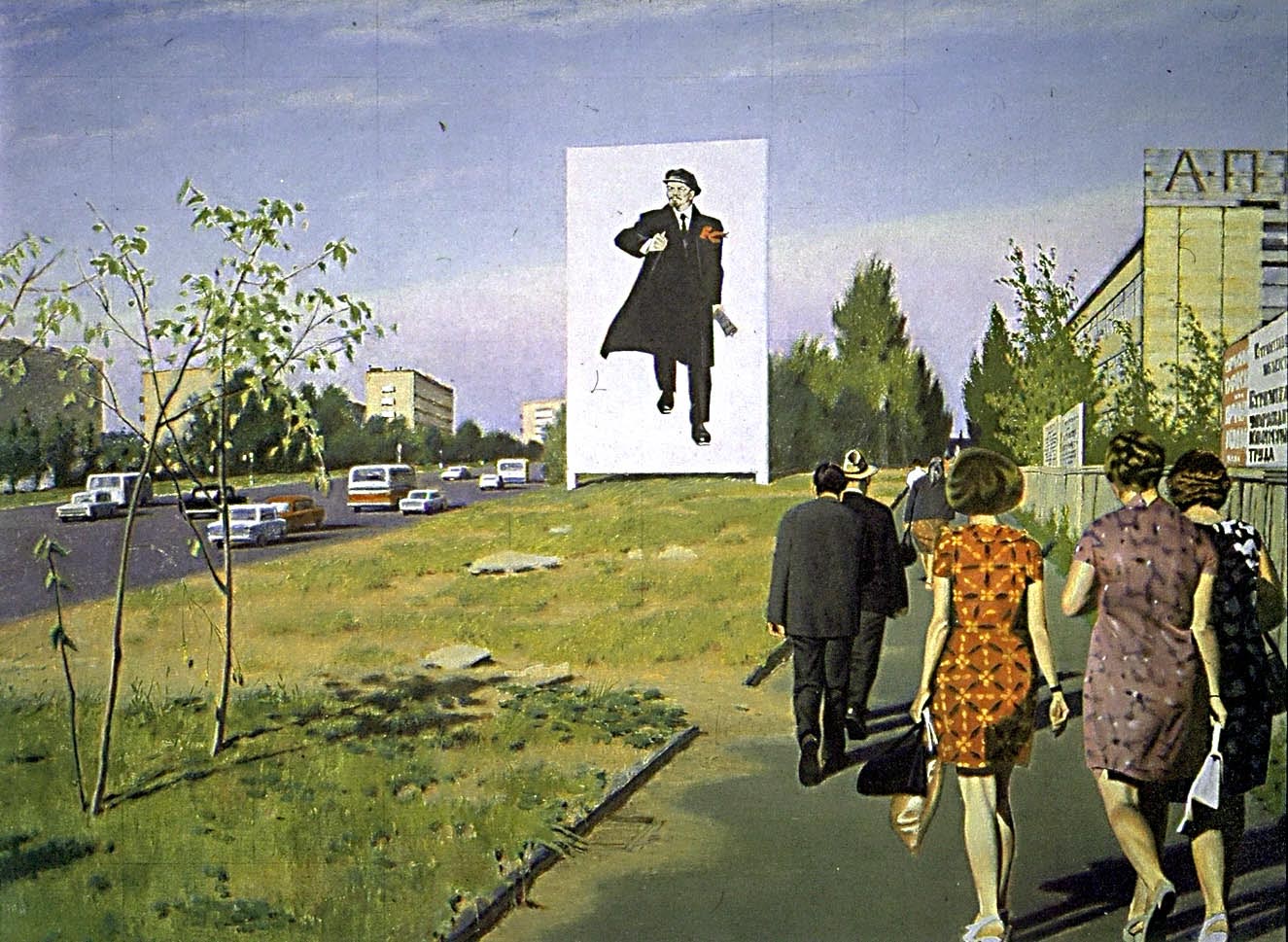

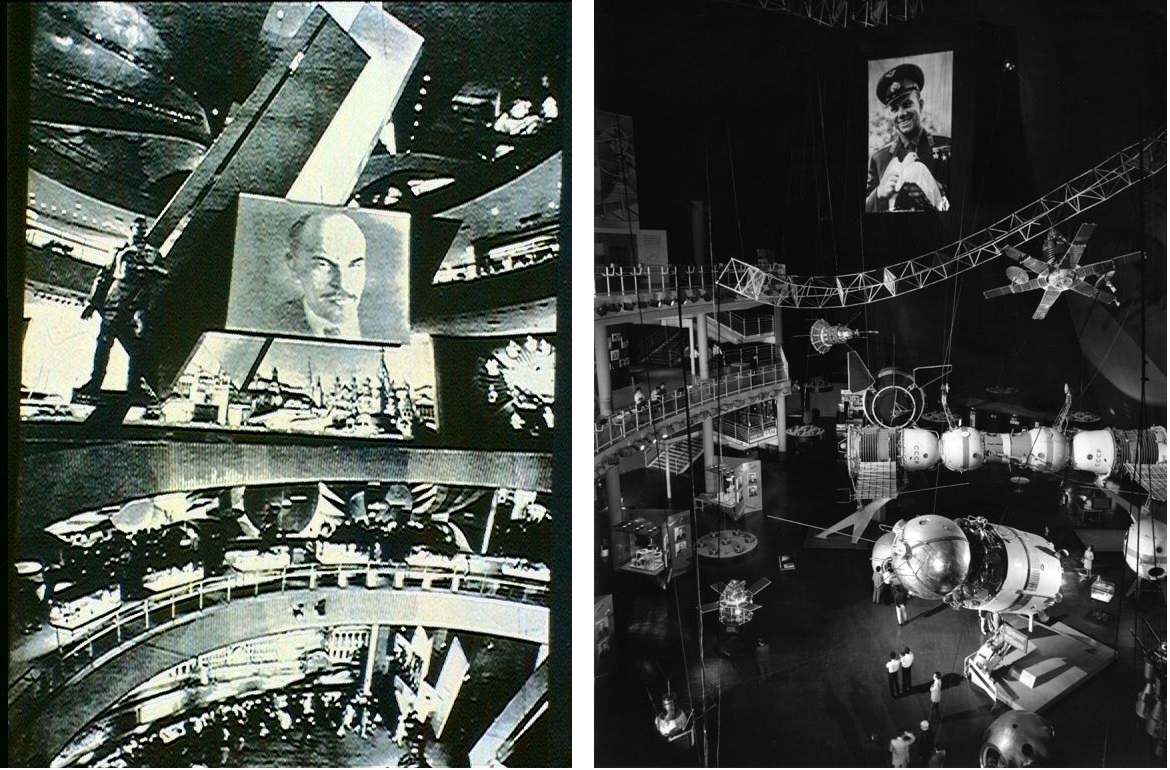

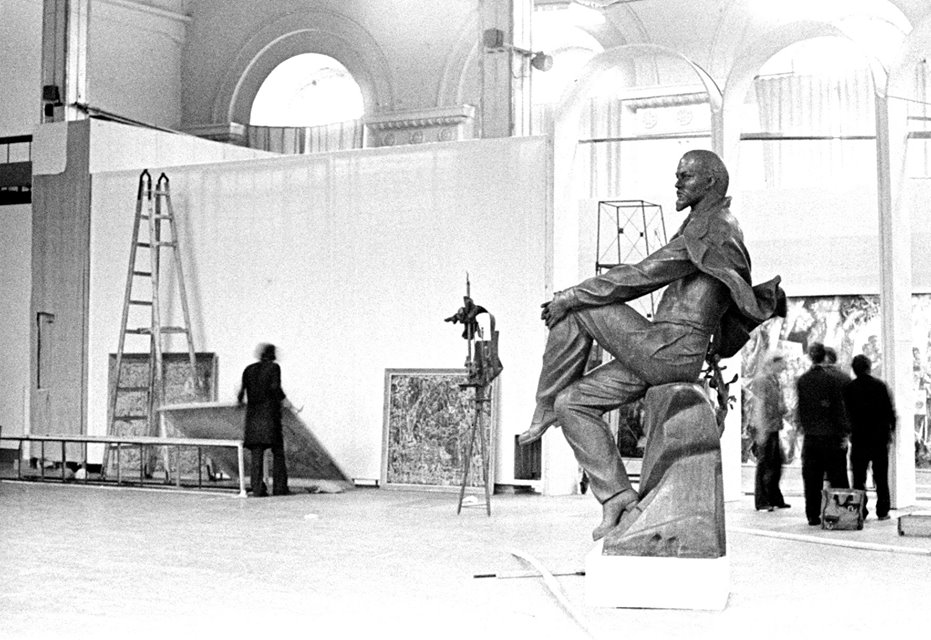

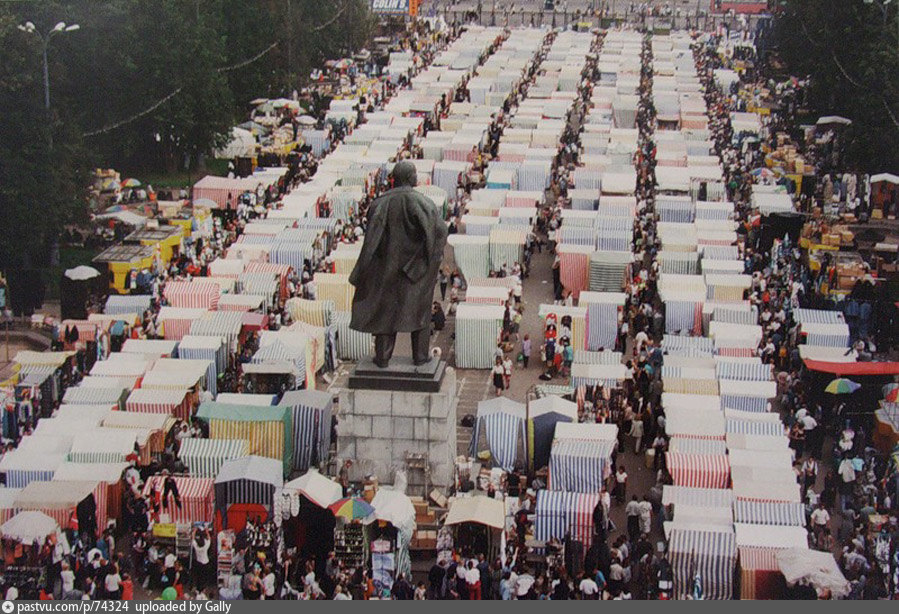

Contemporary Russians continue to live under the visual supremacy of the USSR: communist symbols, monuments, and toponyms are still pervasive elements of the post-Soviet public space. In today’s Moscow one can still find over a hundred of monuments to Lenin and hundreds of memorial plaques, commemorating, quite literally, every step made by the revolutionary leaders of 1917. Needless to say, these objects are not (critically) reframed by the current municipal authorities.

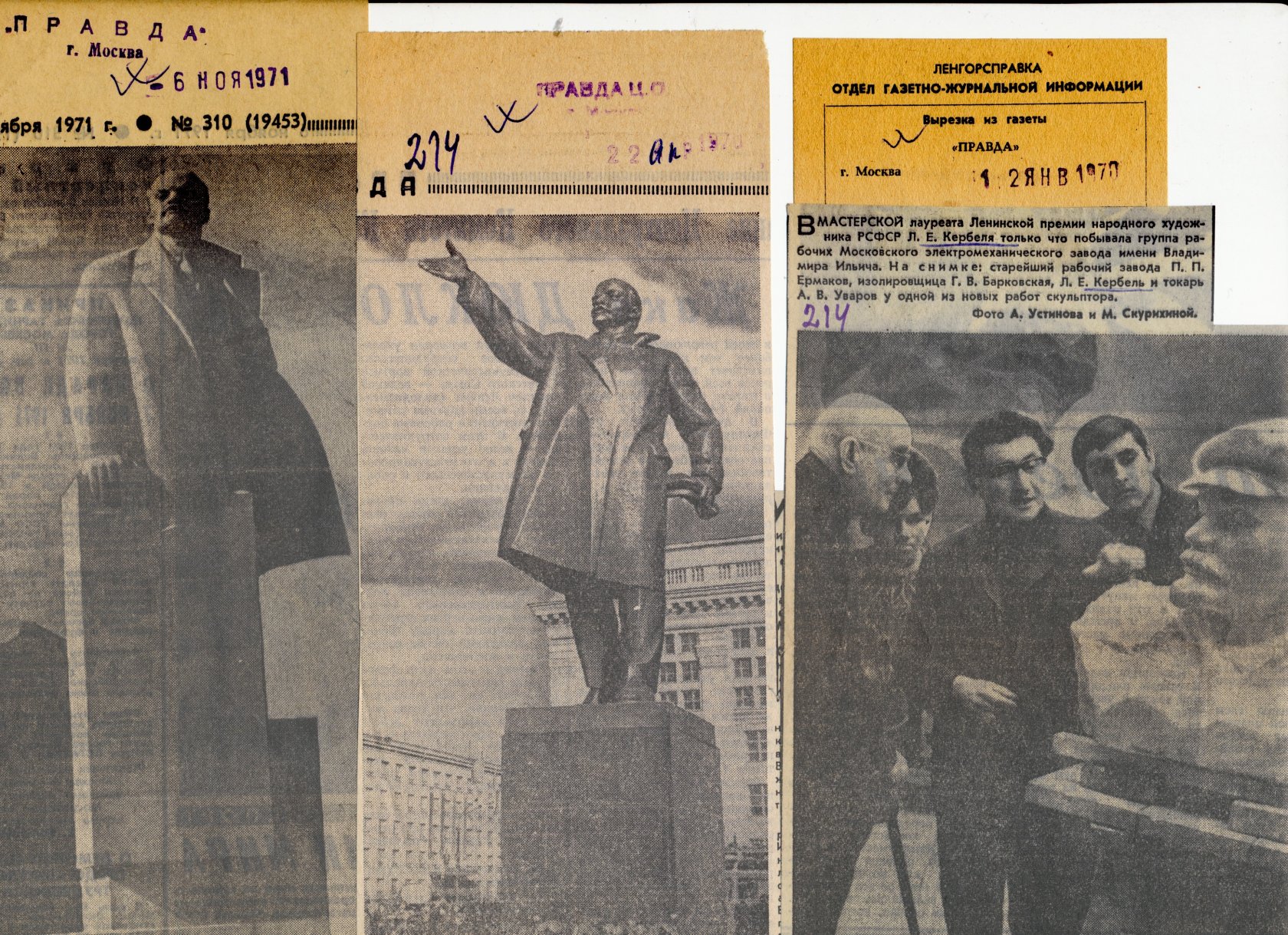

The commemoration of Vladimir Lenin in Soviet art was an archetypal modernist campaign that can serve as an excellent illustration of the commodification of public art and memory. Theoretical reflections on this subject did not begin in Western academia up until the 1960s [1]. While the cult of Lenin itself has been thoroughly examined, almost nothing has been written about the production of the statues of Lenin and their distribution across the Eastern Bloc [2]. The institutional history of the most powerful commemorative gesture in Europe — the dissemination of visual Communist symbols — is still awaiting its researchers and chroniclers [3].

In what follows I will consider the ways of producing, distributing, and promoting monuments to Lenin in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and will reflect on their function and legacy in contemporary public space. I will examine 1) the techniques and methods employed in the production of the statues of Lenin 2) the creation of a network of rituals and traditions, centered around these monuments. Finally, I shall contemplate the outcomes of the commemorative campaign geared towards the immortalization of Lenin in post-Soviet Russia.

It is noteworthy that the groundwork for the dissemination of the cult of Lenin was laid even before his death in January 1924. The first museum collection of Lenin’s works and personal items, such as paintings, photos, private letters, etc. was supposed to be exhibited in May 1923. By then Lenin had already been terminally ill [4]. When he died the following year, there was no hesitation or uncertainty as to how his memory should be preserved. The Commission of the CEC (Central Election Commission) of the USSR for the Immortalization of the Memory of V. I Ulyanov-Lenin was established with an explicit purpose of organizing Lenin’s funeral and overseeing proper memorial ceremonies [5].

Lenin died on January 21, 1924. Two days later, local authorities in Petrograd decided to rename the city into Leningrad (literally the city of Lenin) and to erect a monument to the deceased Bolshevik leader. Five days later, it was decided to build a crypt and a number of monuments in the largest Soviet cities. Six days later, municipal authorities in Moscow launched a fundraising campaign to erect the “greatest monument to our leader.” In conjunction with these proposals other commemorative and propagandistic initiatives gained momentum, such as the resolution to publish the complete works of Lenin, to set up Lenin Corners (a social center of sorts equipped with benches and chairs and shelves lined with books, journals and magazines, where workers or soldiers could read, play checkers, listen to the radio and consult the helpful staff that was always eager to clarify the readings or answer questions — translator’s note), to establish a Lenin Foundation and so much more. In May 1924, only four months after Lenin’s death, the first museum dedicated to him was unveiled [7].

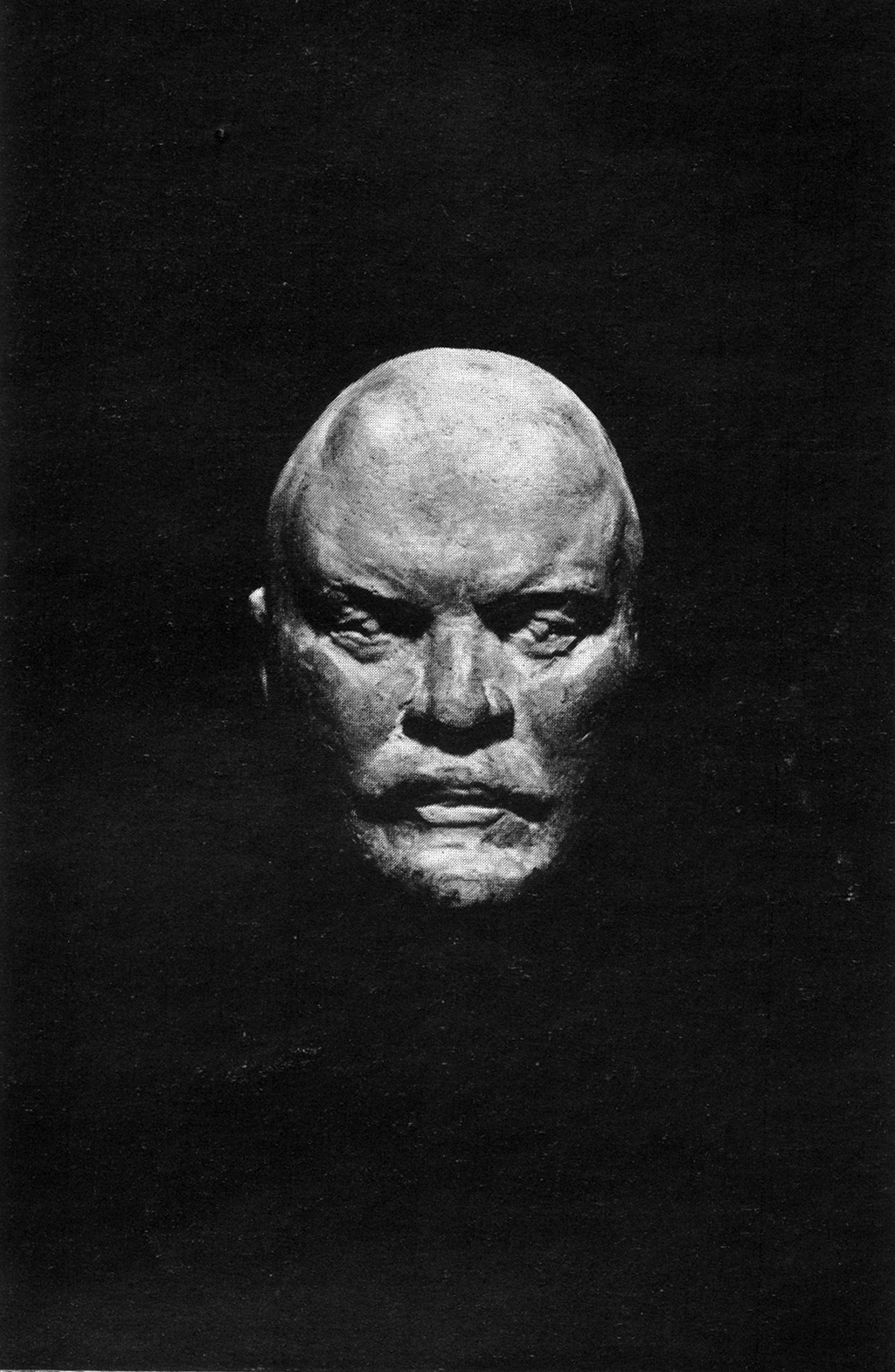

Shortly afterwards Leonid Krasin, one of Lenin’s closest associates and comrades, a Soviet diplomat and the head of the Commission for the Immortalization of the Memory of V. I. Ulyanov-Lenin, published an article “On architectural commemoration of Lenin” in a volume titled “On Lenin’s Monument.” Krasin proposed to erect a mausoleum by deciding on the design of the future crypt and argued that a realistic image of Lenin’s facial traits (i. e. his portrait without any stylization of his appearance) should be preserved as well, since according to Krasin, this would convey the personal charms of the deceased Party leader [8].

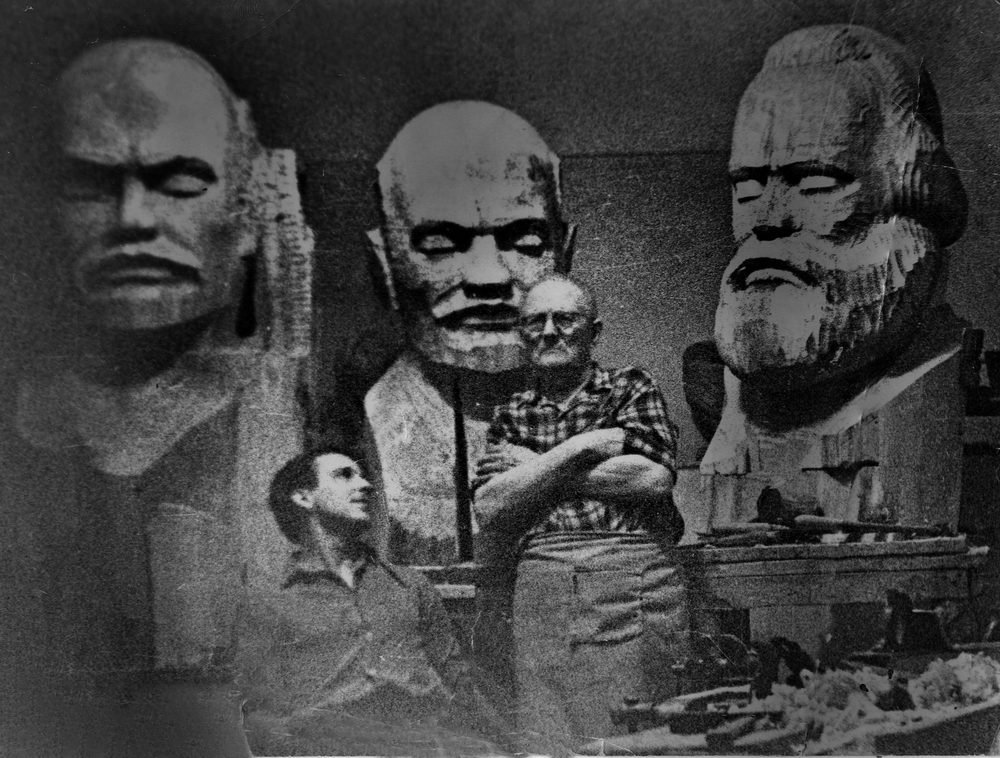

Soon enough depictions of Lenin did assume truly scientific precision, consistency and regularity. Two basic principles at work were thought to guarantee the highest quality of any monumental portrait: 1) people who had been personally acquainted with Lenin were invited to consult the artists working on his portraits, 2) artists had to study Lenin’s photographs to ensure documentary authenticity of their own work.

However, the first monuments presented to the public showed that these early portraits of Lenin lacked the necessary artistic and, more importantly, documental quality. That is why in June 1924, half a year after Lenin’s death, the CEC issued a Resolution on the reproduction and distribution of busts, bas-reliefs, etc. carrying the image of V. I. Lenin. Besides the central Commission, which was based in Moscow, local branches were also established in Leningrad, Ukraine, and Transcauscasia. They were called upon to exercise control over the production of portraits and other images of Lenin [9]. Besides being endowed with the authority to censor productions deemed improper, each commission was obliged to have one member in its ranks who had personally known Lenin. The practice of inviting people who had been personally acquainted with him or even met him once, however fleetingly, in order to consult sculptors or painters, persisted for decades to come.

Just how such consultations were held can be surmised from an excerpt of the transcript of a discussion around the project for the monument to Lenin in his native Ulyanovsk in the later 1930s. The renowned sculptor, Matvei Manizer, who was working on his project, was advised by none other than Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krupskaia. When examining the maquette of the future sculpted portrait, Krupskaia noted: “[You depicted him with] an imperious face. The shape of his body is accurate, though, but the face is supposed to show much more agitation. When he stands in front of a crowd of workers his face is much more agitated as he is trying to persuade them. When he speaks with his political opponents his facial expression is totally different, though [10].”

Realism was key to the depiction of Lenin’s physical appearance. However, a special, rather sophisticated allegorical language was elaborated in order to depict his clothes or posture as is evinced in the words of the local Ulyanovsk official: “We had some discussion about the proposal for a statue, [and we mentioned] that it would be too windy around it. But Lenin’s entire life was such that he always stood firm against stormy winds [11].”

Over the next thirty years this much-debated monument was copied several times. In 1938 it was erected in Ulyanovsk; in 1960 a slightly modified version of it appeared in Moscow and finally, seven years later, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of Lenin’s birth it was unveiled in Odessa.

Some artists, such as Ivan Shadr and Sergey Merkurov, were invited to Lenin’s deathbed to draw and sculpt his body and face, to capture the last minutes of his evanescent appearance. However, it was photography that quite naturally became a far more popular source for artists portraying Lenin for many years to come. A photo album titled 1927 Lénine album. Cent photographies was published in 1927, with captions in Russian and French [12]. By the late 1930s, as Joseph Stalin’s cult of personality had come to dominate Soviet culture and society, the sculptural or pictorial image of Lenin underwent little if any artistic evolution and was somewhat “frozen” or “suspended”, with no new photo albums or new sources published to promote stylistic modifications or transformations. The only exception — the publication of a single album with selected art works depicting Lenin — only went to show that the range of visual sources available to artists at the time was severely limited [13].

Lenin’s political and visual legacy came under scrutiny and revision twice: the first time it happened in the wake of the so-called de-Stalinization of 1953−1961 and took twenty years to crystallize. The new era of commemorative practices dedicated to Lenin started in 1969−1970. It was not until 1970 that two volumes of his photos and movie-stills (a total of 343 images) Lenin. Collection of Photographs and Stills were published to honor the 100th anniversary of his birth (the book was republished again in 1980). Not only did it contain the most comprehensive collection of photos and film stills to date, capturing the slightest movement of Lenin’s body and face and the most flattering angles, but it also included an extensive and very thorough description of his appearance, almost an ekphrasis [14].

The second wave of revisions swept across Lenin’s commemorative cult during the era of Gorbachev’s glasnost’ (1985−1991) that inspired critical reexamination of Leninism and triggered renewed interest in Lenin’s image and legacy [15]. Though stylistically the images of Lenin dated from this period evolved and changed as the artists sought to uncover the simplicity and ingenuousness of Lenin’s personality, the sources that inspired them remained the same: painters and sculptors merely altered certain minor details of clothing and posture.

In the age of photography, the Bolsheviks succeeded in employing and promoting the bourgeois art of sculpture as a proletarian art form. They also drew on the powerful ideas of the Enlightenment, such as the cult of grands hommes, as well as on the practices of the French Revolution and the cult of psychological, scientific, and factual accuracy in portraying distinguished public figures that dates back to the times of the Third Republic [16]. These ideas became deeply entrenched in the Soviet culture, all the more so due to the structure of the modernist production: the rapid creation of a very specific proletarian culture with its own traditions, lieux de mémoire, and “imaginary memories” [17]. All the above mentioned initiatives staked the boundaries of a full-fledged artistic industry that encompassed commercial sculpture manufactories and enterprises that produced millions of copies of Lenin images for mass market, and an impressive range of commemorative practices and rituals, such as newspaper and magazine articles regularly appearing in the press, school trips to memorial sites and monuments, tourist guidebooks and so much more.

There were three main reasons behind the government’s eager support of the distribution of mass-produced statues to Lenin. First and foremost, the nascent country did not yet have a developed network of artists and culture-makers and the former ties connecting artists and art buyers were shattered or lost in the new economic and political reality. Cultural goods could only be distributed by and through the central authority that consolidated in its hands the entire system of production and distribution.

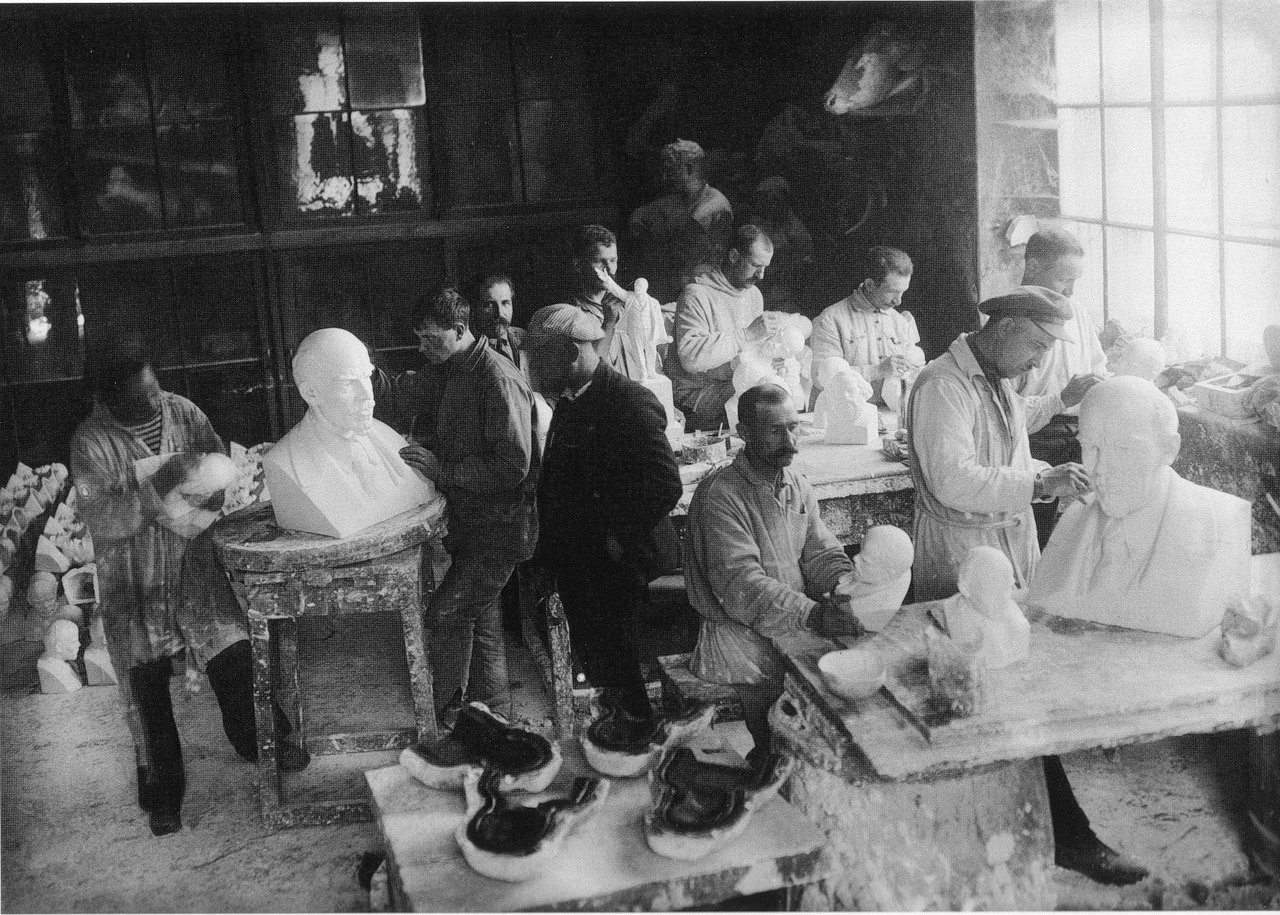

The first manufactories to produce monuments Lenin were set up immediately after his death in 1924, a project spearheaded by the modernist sculptor Sergei Merkurov. Merkurov was educated in Munich and had come under a very strong influence of the Fin de siècle agenda, which ultimately led him to become one of the most prominent creators of death masks of Russian public figures, including Lenin. In the new post-revolutionary reality, it was Merkurov who proposed to launch the mass production of images of Lenin to supply the new Soviet socialist society. His proposal was endorsed by the State Publishing House (Gosizdat) that took care of advertising and distribution of the statues and busts [18]. Later on this private initiative turned out to be one of the most successful and long-standing commemorative projects. That is why Merkurov’s enthusiasm and his initiative could not but boost the dissemination of the unified Soviet culture and ideology.

1928 saw the establishment of Vsekokudozhnik (The All-Russian Cooperative Association of Artists), a semi-private, semi-public enterprise that laid the groundwork for the socialist artistic industry for many decades to come [19].

The second reason behind the Soviet government’s endorsement of Merkurov’s initiative was rooted in the ideology of the Soviet economic system of the early 1920s, which gave no hope and left no space to any private art buyers, and at the same time promoted a form of “state capitalist” economy. Lenin died in 1924, at the height of the so-called New Economic Policy, NEP (1921−1928). The system, which had been previously built upon a network of private collectors, overnight became a rigid structure composed of the nationalized manufactories, art collections, and the likе, whose main task was to guarantee continuous supply of ideological goods/productions across the nation. Soviet artists were eager to take part in that new public system of production and distribution that guaranteed regular and secure commissions from the state. After the revolution of 1917 they lost all their patrons and sponsors and by 1920s were obliged to pay considerable taxes since the new state regarded them as “exploiters” – private employers of labor [20].

The third reason that prompted the Soviet government to support the distribution of the mass-produced statues of Lenin had to do with the emergence of the new type of socialist, anti-hierarchical system of dissemination of intellectual production. The anonymous character of production, mechanized labor, and the idea of justice and fairness (i.e. unified system of payment), appealed to early Soviet thinkers and artists alike, particularly those that belonged to the Left Front of the Art (LEF), popularized in Western Europe by Walter Benjamin in his 1934 essay Der Autor als Produzent (Artist as Producer). In the words of Benjamin “the rigid, isolated object (work, novel, book) is of no use whatsoever. It must be inserted into the context of living social relations” [21]. This was in tune with the Soviet brand of Marxism as well.

New monuments and public images of Lenin created by the Soviet government had to be contextualized. As Benjamin put it in 1936, the technical reproduction of art has no authority of the original which in turn leads to the independence of a reproduced work from the tradition, the ritual and the place, and its existence is based only on politics. Politics has the power to create new traditions and to abandon the old ones. Benjamin compared the dissemination of reproductions with architectural phenomena — building space is something that we get used to through constant repetition [22]. This is exactly what happened to the commemorations centering on Lenin: a system emerged that smoothly distributed images and at the same time worked to disconnect them from local or recent political traditions just as smoothly.

The principles of anonymity, standardization and mechanization that characterized the operation of “Vsekokhudozhnik” with its integrated manufactories turning out mass-produced images, sculptures, busts and paintings, defined the socialist method of creation for the anti-hierarchical, and even more importantly, anti-exploitative, anti-predatory socialist culture.

Soon enough, every minute detail of the production process was thoroughly elaborated. Standard contracts were drawn up for the artists that were commissioned to create models for the mass-reproduction in accordance with the production plan and thematic calendars. Standard pricelists were also put together. An original artwork had to be scrutinized by a special commission: in the case of images of Lenin it was The Commission of the CEC (Central Election Commission) of the USSR for the Immortalization of the Memory of V. I Ulyanov-Lenin that was responsible for such an examination. Images of Lenin were among the most expensive works. The fact that there existed a direct correlation between the significance of the subject and the remuneration received by the artist was duly noted (not without a certain wry irony) but many a private diarist as early as 1925 [23].

By the 1950 both the prices and the themes had been tailored in accordance with an elaborate hierarchy of genres and artists, giving rise to a corrupt system of privileges. Giant factories and industrial plants were key consumers of the mass-produced copies of statues of political leaders, such as Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin (as well as Leon Trotsky and Genrikh Yagoda before both of them fell from grace). These sculptures were needed to inscribe public spaces such as squares, railway stations, workers’ clubs and the like, with visible symbols of the state and the Party.

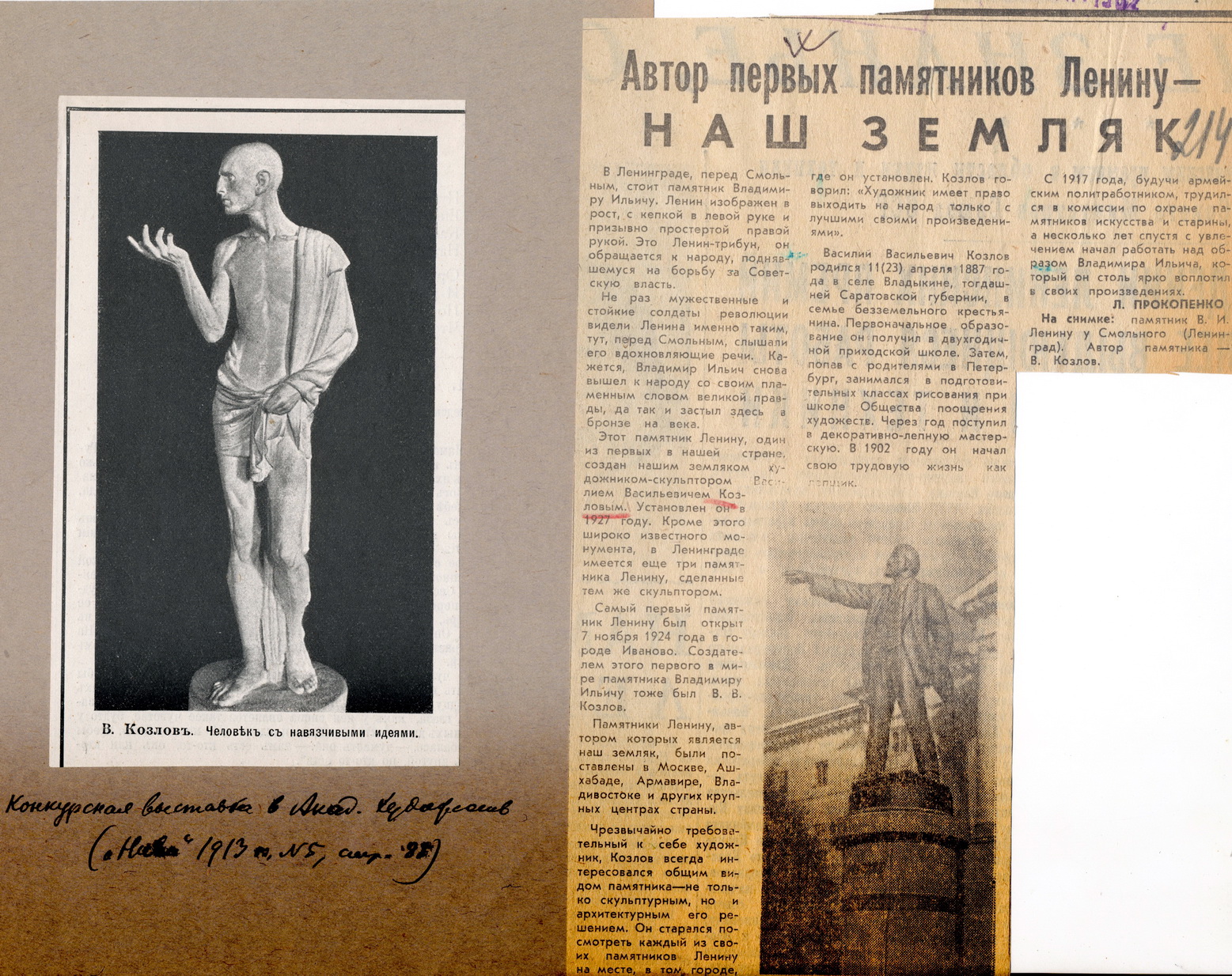

Considering the relatively small number of authorized sculptors entrusted with such commissions (by the mid-1930s their number ranged between five to ten people), the sheer number of copies of monuments produced was staggering. For example, in 1932 Vassily Kozlov, a sculptor, whose carrier had been started by the late Tsarist times created more than 40 public monuments to Lenin and hundreds of busts for Soviet public spaces [24]. Another popular model designed by Georgy Alekseev and approved by a special state commission was replicated in 10 thousand copies [25]. In 1950 the process of replication was brought under regulation: now artists were expected to copy not the original work, but only the pre-approved reference samples or master samples: in effect, we are talking about “copies of copies” here [26]. In his private letter to the People’s Commissar for Education Andrei Bubnov (arrested and purged in 1938) Boris Korolev, one of the most prominent sculptors of the 1930s complained bitterly about the situation in this field: “Over the past fifteen years, opportunism, spiritual poverty, blatant ignorance and the cold empty formality have left ineffaceable traces on all of the widely proliferating sculptures and the entire domain of public art [27].”

Indeed, the discrepancy between the works of sculptors, routinely using photographs of Lenin as their reference sources and turning out mass-produced copies of his image on the one hand, and the official policy of the regime that called for authenticity and verisimilitude in sculptural representations of the Bolshevik leader was truly striking [28]. Moreover, with the outset of Stalinist terror party activists eagerly seized on the idea that low-quality mass-production promoted by disgraced functionaries and officials, was really damaging for the Soviet art, an accusation, which was particularly widespread during the purges of 1936−1938 [29]. Yet at the same time, following the annexation of Western Ukraine and Belorussia in 1939, local manufactories were swiftly converted into wholesale mass-production operations. “In Kiev, Kharkov, Dnepropetrovsk, and Lviv these manufactories should have become the hothouses for the creative growth and development of local sculptors. In reality, however, they have been converted into commercial enterprises that focus exclusively on mass production [30].”

Vsekohudozhnik was disbanded in 1953, although it had already begun to lose some of its influence back in the late 1930s, when the majority of the most prominent members of the cooperative were arrested and purged. Its property was passed on to the Artistic Foundation of the USSR (Khudfond), which had remained one of the monopolists in the field of art production and distribution up until the collapse of the USSR [31].