Perhaps all writing of history presumes an absence or lack, which is one of the conditions that compel the historian to write. One form of absence resides in the object of study itself. It is an absence that, qualitatively, may be meaningful and crucial, or perhaps ancillary, anecdotal, or arcane. It may be total: the object may be previously unknown or mostly unknown (the historian’s dream come true). The object of study may be incomplete or may have been incomplete, it might have been corrupted, or perhaps its inherent attributes were imperceivable before the moment of writing. Another kind of absence emanates from outside the object of study, arising from a perceived lacuna in a discourse, discipline, or practice. The object may have been miscategorized or misidentified. External factors may have led it to be intentionally or unintentionally overlooked, underappreciated, or misvalued. Forgetting and amnesia play a role in external absences, as does the possibility that the object was subject to suppression, exclusion, erasure—an act of epistemic violence. The first kind of absence implies that the act of writing history provides missing information, whereas the second suggests the correcting of an error, omission, obfuscation, or prejudice. Of course, the distinction between these two absences is artificial, insofar as both require an author to establish the nature of the absence that the writing of history reveals or redresses, in relation to which she establishes a perspective or method—keeping in mind that perspective and method (systems of knowledge, models of reading, ideology, author positions, etc.) are never neutral or objective and may be the reason for the absence.

In addition to the above incomplete, myopic schema, there are at least two other forms of absence that complicate the historian’s task: uncertain absences and non-problematic absences. In the former, the reason for or nature of the absence is unclear, even after digging, studying, and researching. The object of study itself proves mute or opaque, sometimes to such a degree that one can only infer its nature by looking at its effects (or lack of effects) on other objects or on its context (discourse). It is similar to the way in which astronomers study black holes by examining the matter swirling around them. Uncertainty still suggests a method: it means writing around and adjacent to the object of study rather than about it, for there may be no way to approach it directly in a substantive manner. Non-problematic absences haunt every writer—the reason for the lack of appreciation for or awareness of an object may be that it is not interesting or barely affects the discourses around it. It unsettles the writer because she may not recognize its unimportance, or worse, she thinks it is important, only to find out that no one else agrees. The challenge of non-problematic and uncertain absences is that they can be confused and they can overlap. There is a danger in the compulsion to write when the absence is uncertain or non-problematic; it can lead to a tendency to inflate or overdetermine the object. On the other hand, if the uncertainty or problematic nature of the object are left open and made transparent, the compulsion to write remains with the author, and the writing of history may open to unforeseen readings.

The 1954 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition The Modern Movement in Italy, curated by Ada Louise Huxtable, is a veritable black hole, and it is likely a problematic object. [1] Huxtable is best remembered as the New York Times’s prolific architecture critic, a title that she held from 1963 to 1982. She is credited with establishing architectural criticism as a journalistic field in its own right in America, and she is regarded as one of the finest critics of the twentieth century, penning countless reviews both laudatory and biting. Huxtable authored a dozen books, including editions of her collected writings. [2] She received numerous awards, the highest of which was the inaugural Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 1970. [3] She got her start at the Museum of Modern Art: Philip Johnson, director of the Department of Architecture and Design, hired her in 1946 as an assistant curator while she was studying architectural history at New York University. She worked in the Department, contributing to various exhibition designs, until 1950, when she earned a Fulbright Grant to study architecture in Italy. She spent a year abroad based out of the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia (IUAV), visiting buildings and meeting architects, engineers, and planners. [4] It was a critical time: reconstruction was in full swing, as massive government programs (heavily funded with Marshall Plan monies) aimed at the nation-wide housing crisis as well as rebuilding Italy’s industry. As the fledgling democracy took shape, so too did domestic political battles and international Cold War politics, which in Italy were especially intense given the power of the Italian Communist Party and the American government’s desire to blunt its electoral success. Despite the challenges of reconstruction amidst the creation of a new political order, architects produced provocative buildings, urban designs, and products for the home and office. Huxtable could not have chosen a more fascinating moment to be in Italy, or to install an exhibition at MoMA.

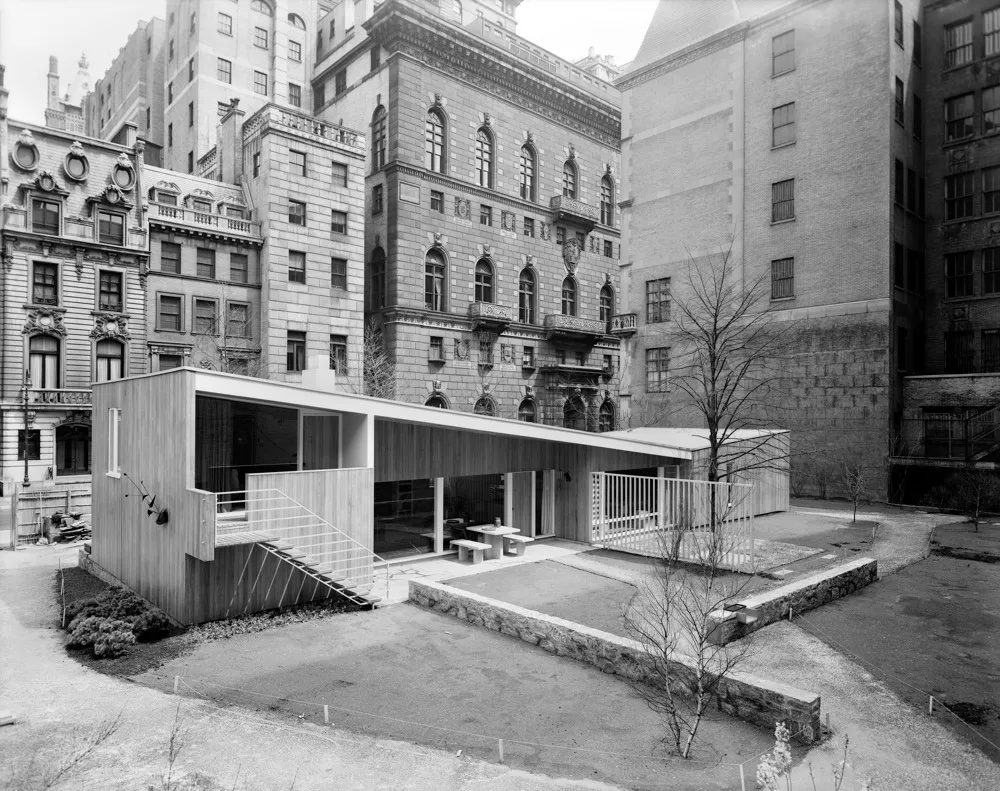

The 1940s and 1950s at MoMA were an intense two decades, hosting landmark shows that transformed architectural culture. Built in USA (1944), curated by Elizabeth Bauer Mock, surveyed trends in American architecture, emphasizing material technique and contemporary lifestyle. Built in USA was a counterpoint to Johnson and Hitchcock’s doctrinaire Modern Architecture exhibit of 1932, as well as the vanguardism of shows regarding Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, European luminaries, and the Bauhaus, and the subtly insecure tone of exhibitions aimed at forging a lineage for an explicitly American approach to modern architecture, such as the survey of H.H. Richardson’s opus. [5] The follow-up exhibition Built in USA: Post-War Architecture (1953) was just as influential, charting, with a kind of triumphalism, eclectic yet undeniably high-quality American approaches to mid-century architecture that were no longer self-conscious and were ready for international export. [6] Conversely, shows dedicated to Buckminster Fuller and to surveys of west coast architecture demonstrated a forward-looking, focused assessment of important domestic figures and developments, while exhibits of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work, famously excluded from Modern Architecture, stood apart from everyone and everything. The 1941 Organic Design in Home Furnishings show, as well as the Good Design program based on eponymous exhibitions staged almost annually from 1950 to 1955, introduced Americans to new lifestyles that married progressive approaches to the home with new materials and techniques. [7] Full-scale demonstration houses by Marcel Breuer, Buckminster Fuller, Gregory Ain, as well as a Japanese house designed by Junzo Yoshimura, all erected in the MoMA garden, allowed the public to physically place themselves inside of design. International retrospectives made crucial contributions to the survey of global architectural trends. In addition to monographic shows, exhibits and publications included Brazil Builds in 1943, Two Cities (Rio and Chicago) in 1947, and Architecture of Japan in 1955. [8]

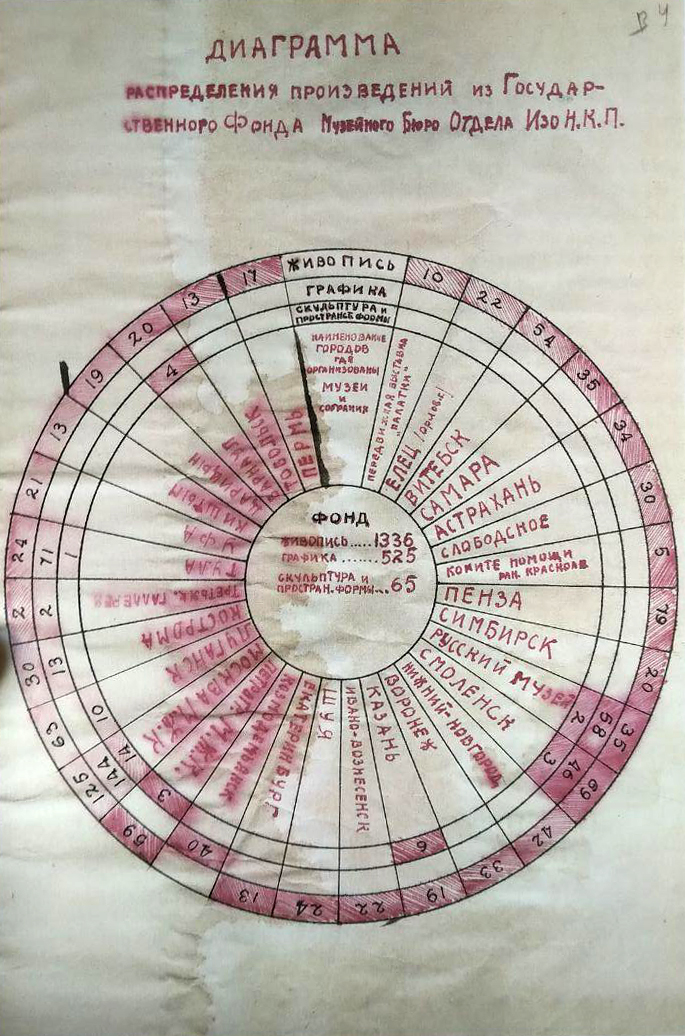

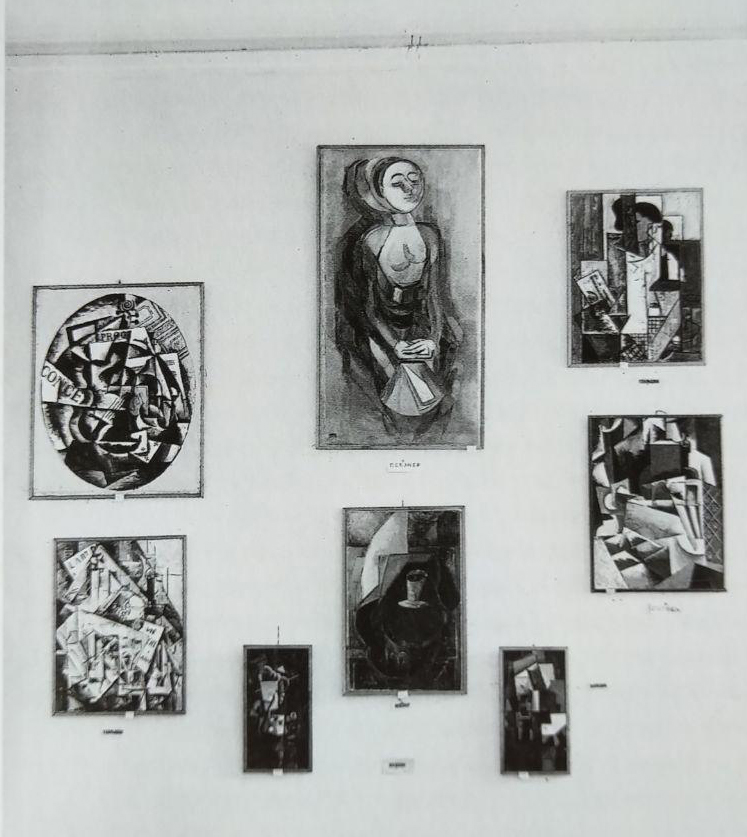

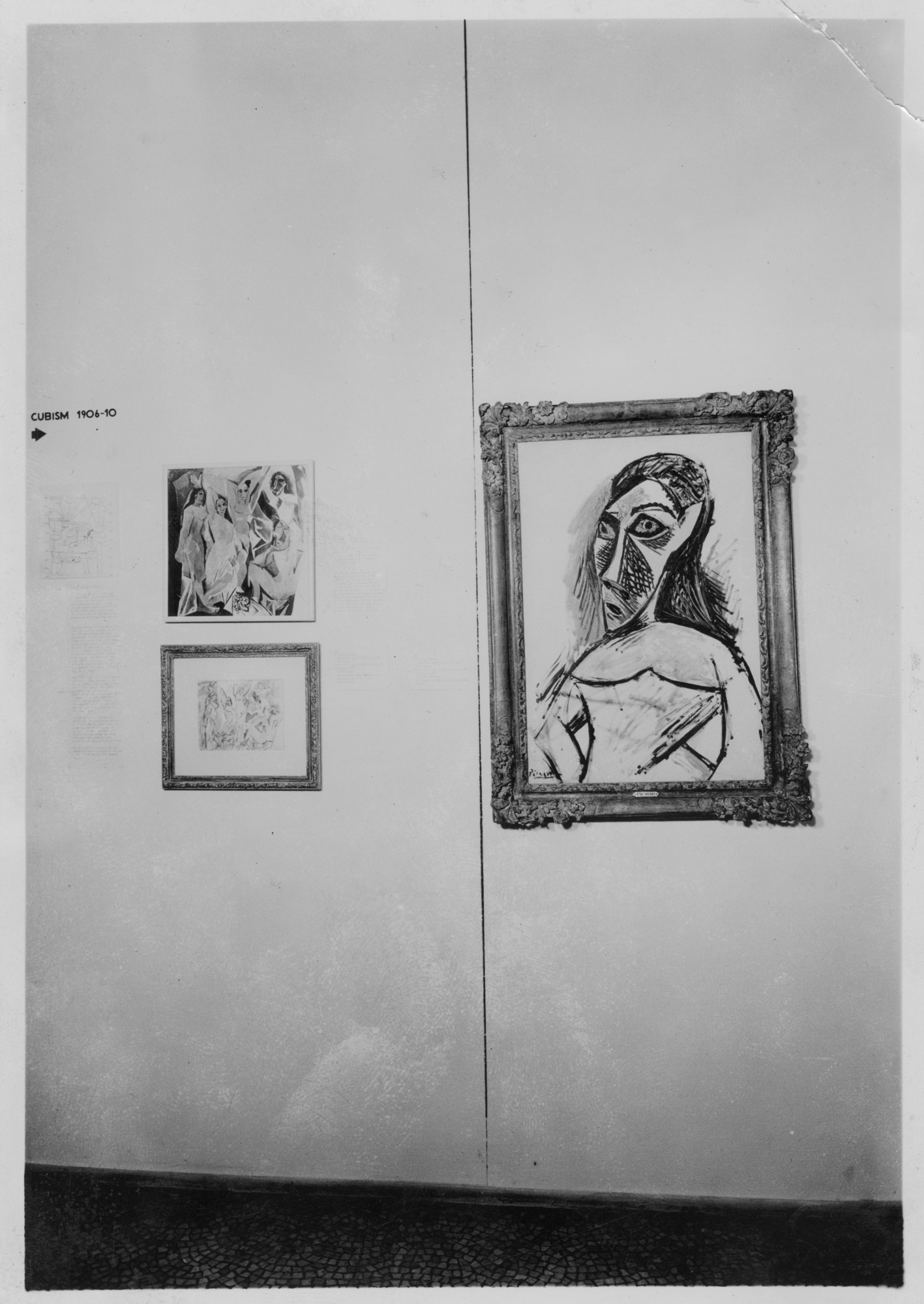

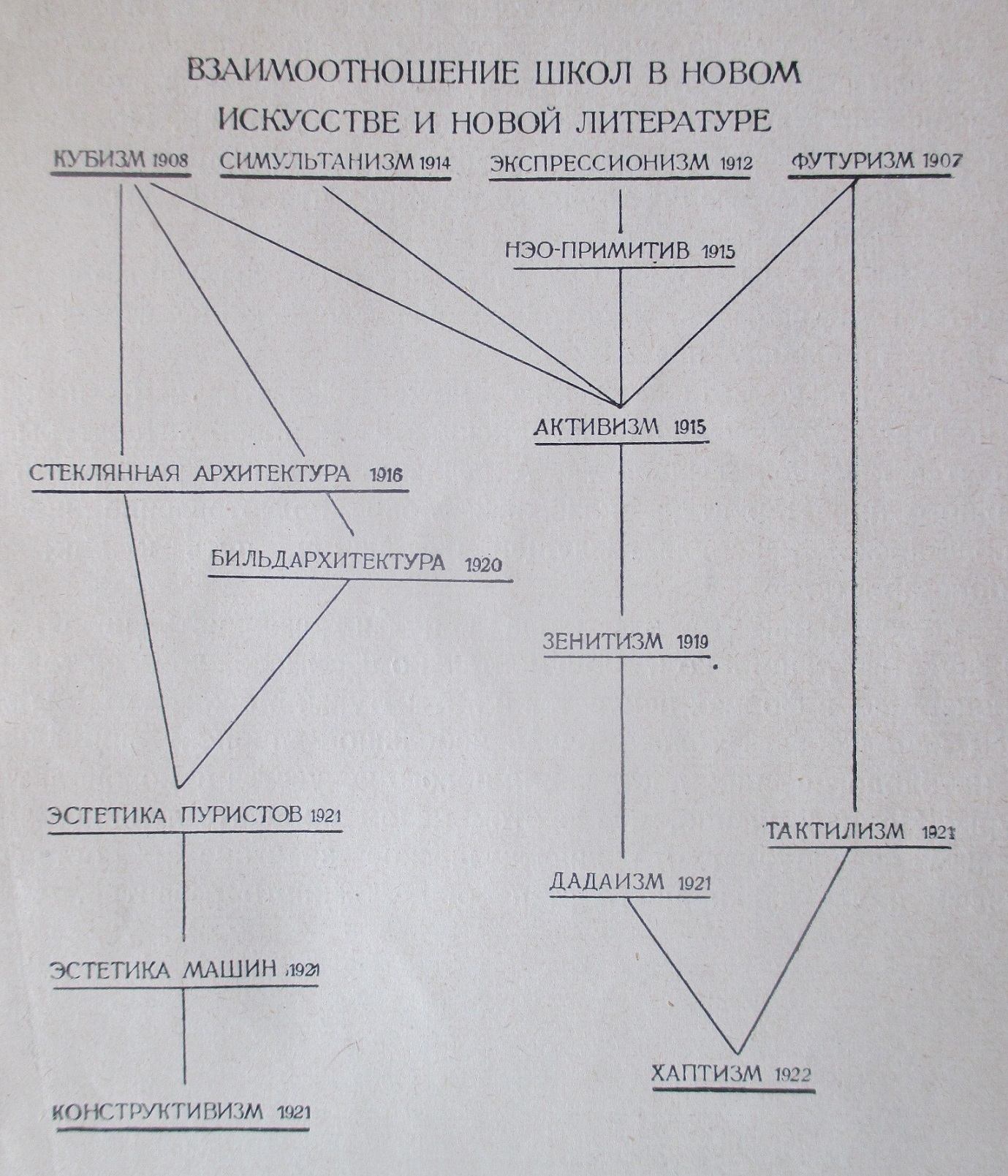

Italy was the focus of two important exhibitions. First was Twentieth-Century Italian Art in 1949, curated by Alfred Barr, Jr. and James Thrall Soby. [9] The epic show codified Futurism’s place in the genetic lineage of modern art (corresponding to Barr’s famous 1936 diagram) while expanding the survey of Italian tendencies to include pittura metafisica, Novecento, and Italian realism. Barr and Soby traveled throughout Italy to study the scene, acquire loans, and make purchases to expand MoMA’s sparse Italian collection. This crucial exhibition was one of many exchanges between MoMA and Italy during this period, which intensified after the Italian Communist Party’s defeat in the 1948 elections, resulting in a greater commitment by the Department of State to using international cultural programs as an instrument of Cold War strategy. [10] Three years later, Olivetti: Design in Industry cut a cross section through the industrial firm’s two decades of work in the factory town of Ivrea, emphasizing the manner in which Olivetti elided design, engineering, manufacturing, industrial objects, and architecture. [11] While the exhibition failed to capture how design was entangled with Adriano Olivetti’s center-left postwar politics and the activities of the Movimento di Comunità, the show launched the narrative of Italy as a progressive nation whose design and home products were synonymous with quality, imagination, and fashion. It anticipated the boom economico and foreshadowed the mid-century global obsession with Italian design.

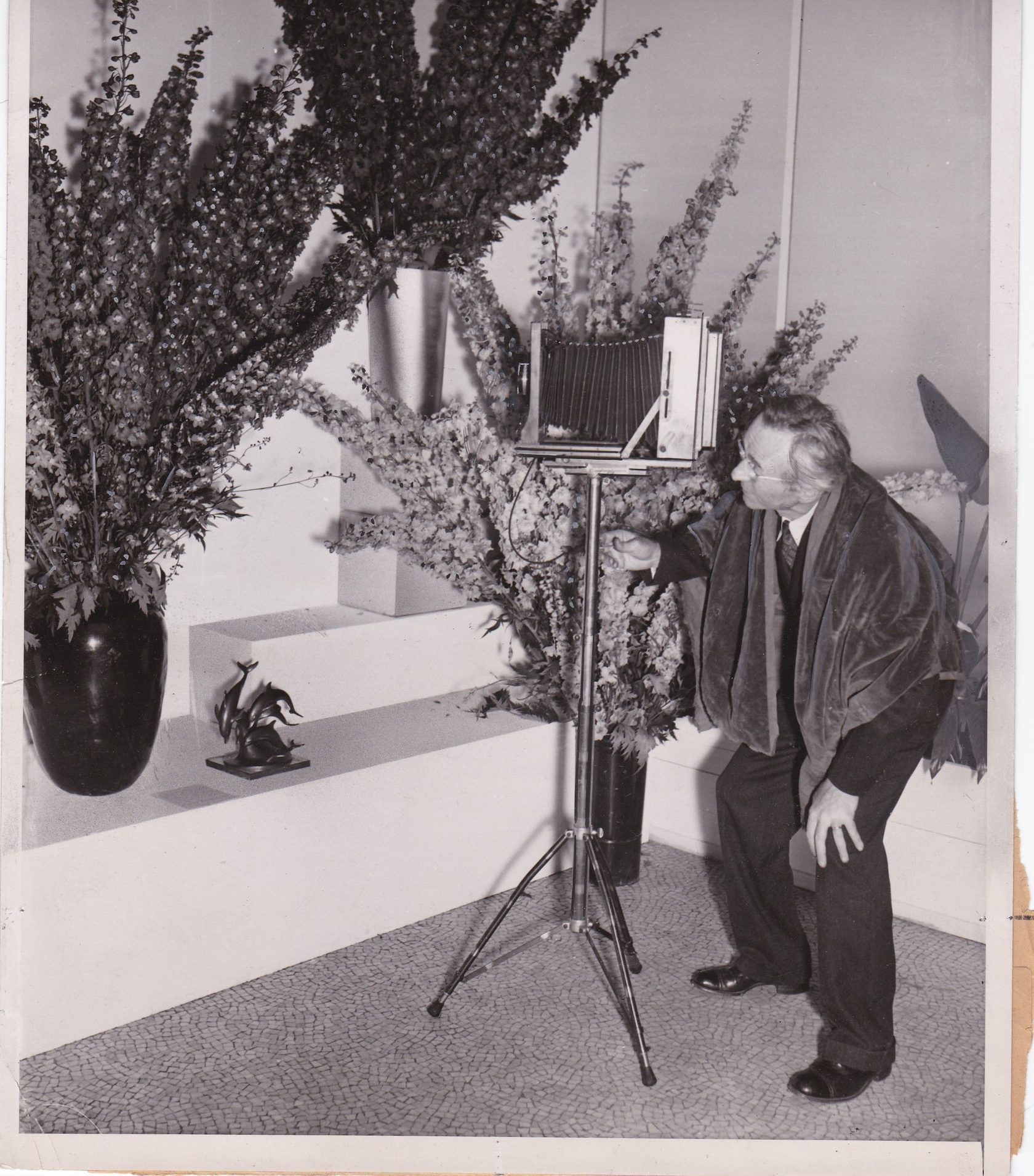

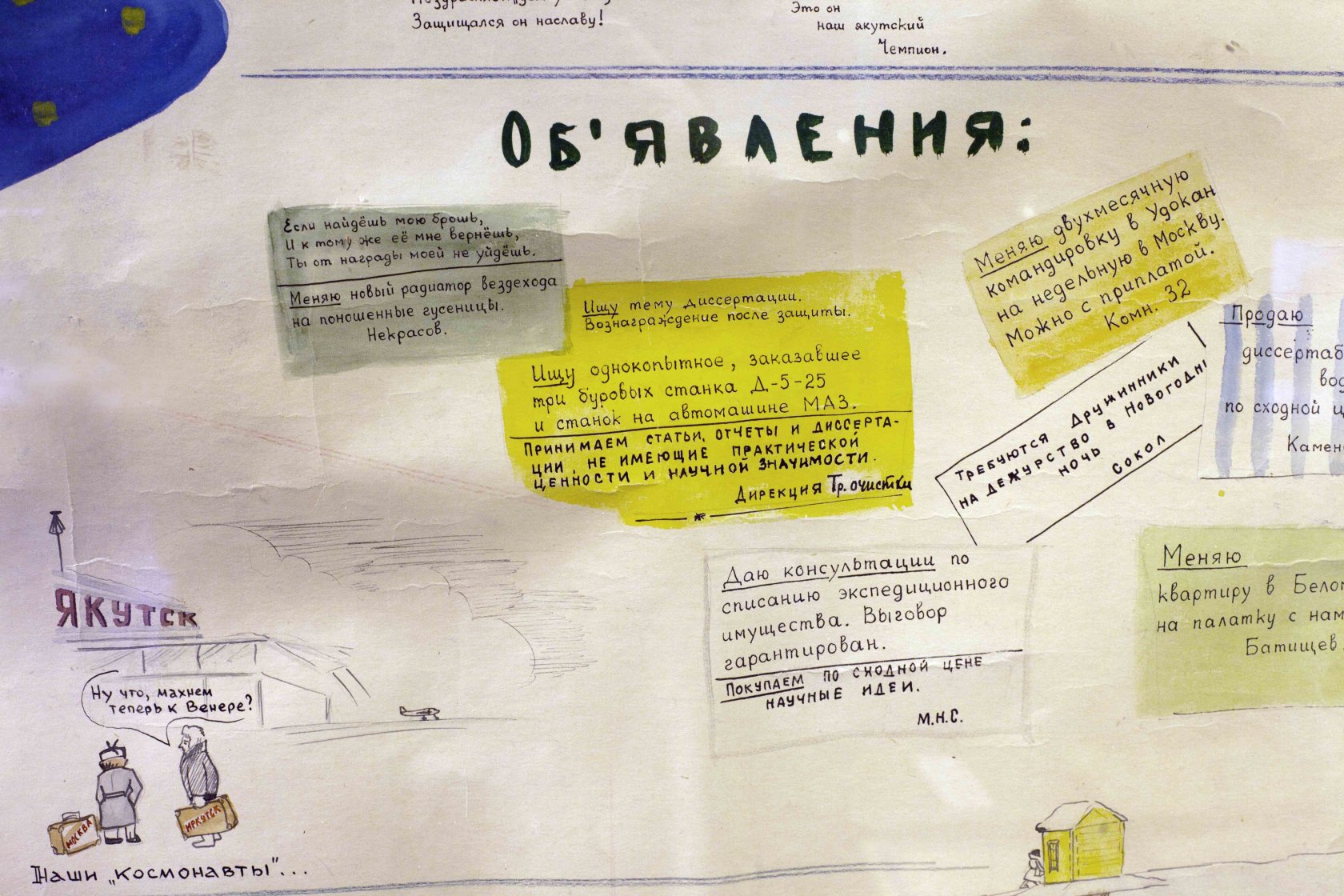

Fresh off her travels, Huxtable returned to an institution that had begun to craft a narrative The Modern Movement in Italy because little exists: save for a positive review in the New York Times, a descriptive featurette in the magazine Contract Interiors, and an essay by Huxtable in Art Digest (where she was a contributing writer and editor), it was ignored by the press. [12] There were no conferences, lectures, or symposia. Conceived as part of an education program of traveling exhibits organized by Porter McCray, director of the International Program that aimed at extending MoMA’s expertise and resources to local museums and universities, The Modern Movement in Italy circulated to nine institutions from the east to west coast, as well as two in Canada—none left a trace. [13] Unlike other exhibits at MoMA, it birthed no books, although Huxtable employed her research in her 1960 monograph on engineer Pier Luigi Nervi. More perplexing is the sparse documentation in the Museum of Modern Art archives: only a few photographs, a checklist, and a press release. The exhibition is not noted in any detail in MoMA’s Bulletins, which usually highlighted retrospectives, even of secondary import. It is telling that in 1964, when a comprehensive survey was undertaken to document the history of the Department of Architecture and Design, Huxtable’s show was left out. [14] Unlike curators such as Elizabeth Mock and Janet Henrich O’Connell, Huxtable is excluded from surveys of women’s contributions to MoMA. [15] To all intents and purposes, The Modern Movement in Italy was a non-event, registering no impact on architectural discourse or MoMA’s legacy. However, a close reading of the exhibition and its context, which focuses as much on what was excluded, may explain why it did not resonate, why it likely served its purpose, and why it was symptomatic of historical, cultural, and political uncertainties that haunted Italian architecture in the 1950s.

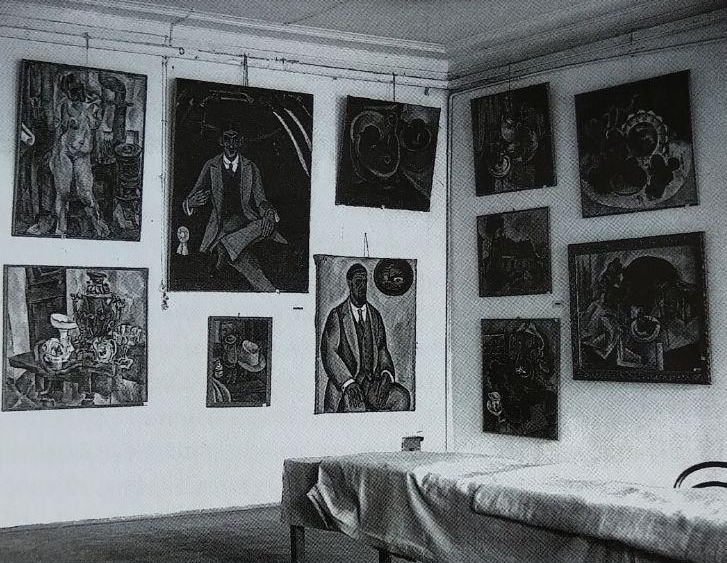

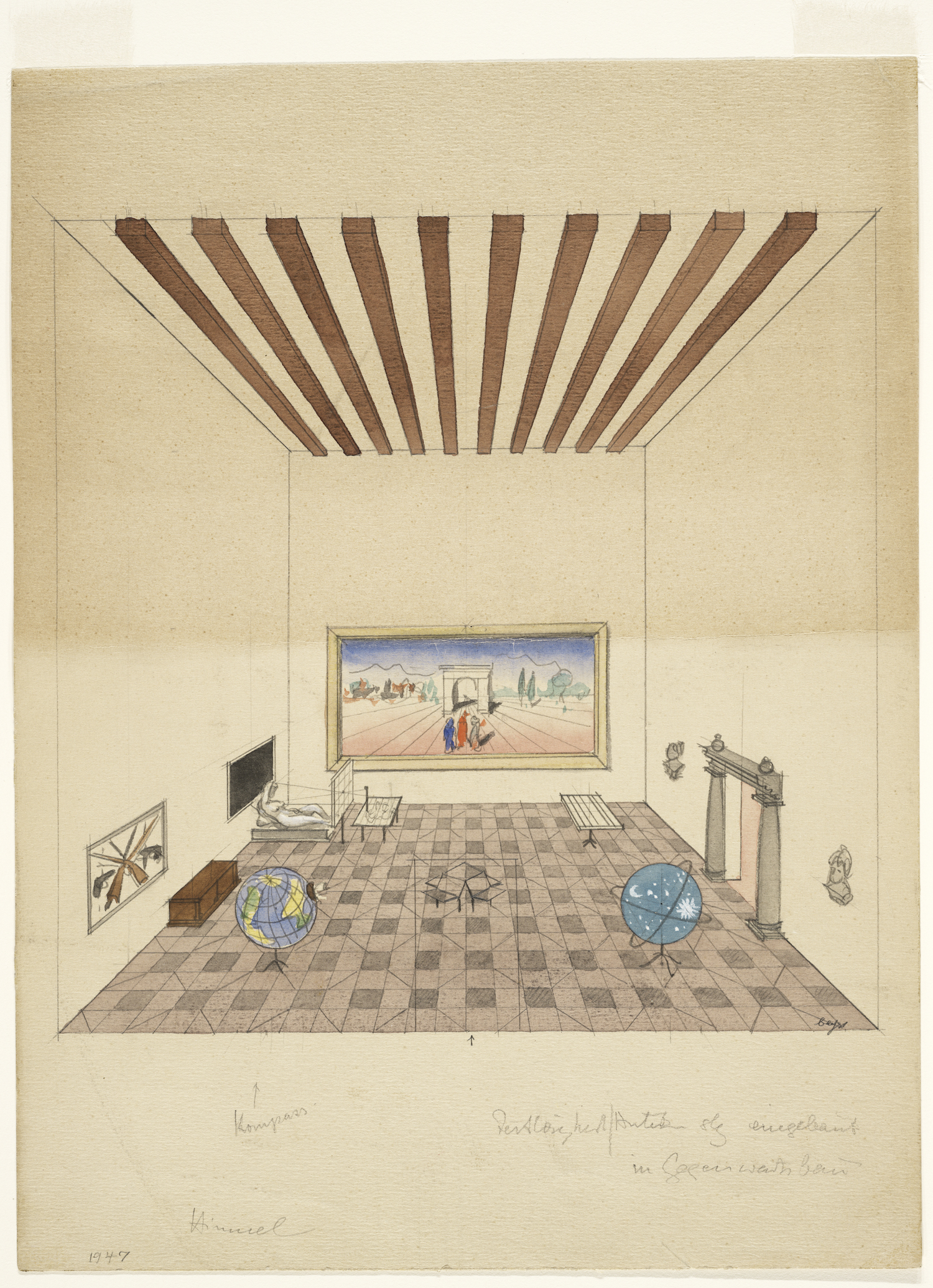

The Modern Movement in Italy was almost entirely image-based, consisting of enlarged photographs of buildings, drawings, and domestic products. The pictorial panels were complemented by a handful of pieces of flatware and glassware, along with sculpture drawn from the Museum’s collection, including a bronze equestrian by Marino Marini as well as Umberto Boccioni’s Development of a Bottle in Space (1912) and Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) which Alfred Barr, Jr. acquired in 1948 from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s widow. [16] However, it is unclear how the sculptures related to the exhibition content, particularly given the absence of Futurist or Novecento architecture or drawings. Rather than tracing Italian modernism’s origin to the Liberty style or Futurism, Huxtable begins in the mid-1930s, claiming that it was only then that the language of the International Style transformed into something definably Italian. [17] She organized her show into five sections: an introductory space which surveyed pre- and postwar architecture; “The Early Work,” which situated the paragon of Italian modernism’s formal vocabulary in the refined Comasco Rationalism of Giuseppe Terragni, Pietro Lingeri, Cesare Cattaneo, and Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini; “Architecture and the State,” a cursory selection of realized works and competition designs for the Fascist regime; the oddly named “The Italian Contributions,” which formed the bulk of the show and surveyed the work of Nervi, the Olivetti Corporation, exhibition design, and commercial and retail architecture; and a miscellaneous collection of “Postwar Work” and “Design.” Despite this structure, the categorizing of projects is at times unclear: Terragni’s Casa del Fascio di Como is placed in “The Early Work” section rather than with works for the State, while the selection of home and office products ranged from glassware to sports cars, without offering a means of understanding their commonalities beyond being Italian. Juxtaposing design objects with architectural masterworks epitomized Ernesto Rogers’s theorem “from the spoon to the city,” which meant that, beyond buildings, Italian architectural practice includes extending taste and quality (i.e., design) to every scale of human life, but it is unclear whether MoMA’s audience understood this message. [18]

Huxtable’s selections are highly consistent, bordering on blinkered. The language of Italian modernism was made explicit through Figini and Pollini’s demonstration house built for the 1933 Triennale di Milano, Cattaneo’s palazzina in Cernobbio, and a Milanese housing complex by Terragni and Lingeri. The Como Casa del Fascio was afforded more images than any other building, positioning it as the apotheosis of northern Rationalism. Huxtable’s choices for representing regime architecture are perplexing: Gardella’s tuberculous treatment facility, the Unione dei lavoratori dell’industria in Como by Catteneo and Lingeri, the unrealized Brera Art School by Figini, Pollini, Terragni and Lingeri, and designs by BBPR, as well as by Albini, Gardella, Romano, and Palanti for the Esposizione Univerale Roma of 1942. These selections misrepresent the scope of Fascist building programs and the Party’s instrumentalizing of modernist aesthetics. Nervi’s works and the Olivetti complex comprise the heart of the show, represented through a dozen designs that depict an array of Nervi’s experiments and offer a comprehensive view of Olivetti’s aspiration for a humane architecture, city, and workplace. The exhibition included images from the 1951 Triennale di Milano as well as works by Franco Albini, and Angelo Bianchetti and Cesare Pea, all three of whose schemes for commercial interiors appear. Postwar buildings shown included housing complexes by Figini and Pollini, the new Roma Termini, a market by Gaetano Minnucci, and a thin-shell concrete market in Pescia designed by Giuseppe Gori, Leonardo Ricci, Leonardo Savioli, Emilio Brizzi, and Enzo Gori. Two memorials conclude the exhibition: the delicate frame of the Monumento ai caduti nei campi nazisti (Monument to the victims of the Nazi camps) designed by BBPR, and the floating monolith of the Fosse Ardeatine—a memorial to Romans murdered by Nazis during the city’s occupation—designed by Mario Fiorentino, Giuseppe Perugini, Nello Aprile, and Cino Calcaprina.

Huxtable’s approach to establishing the lines of Italian Modernism is doctrinaire: she asserts that it was only through a conscious break with Italian traditions that a “mature” architecture took hold. [19] Notwithstanding the press release claiming that the show features Huxtable’s original research, the images that she used are almost all iconic photographs that had been published in Casabella, Domus, Architettura, and Quadrante. Nearly all of the pre-war works are found in Alberto Sartoris’s atlas Gli elementi dell’architettura funzionale, the third edition of which, published in 1941, undoubtedly served as a reference for Huxtable. [20] By declaring Terragni, Lingeri, Cattaneo, and Figini and Pollini the leading visionaries of the interwar era, Huxtable privileges the most polemical experiments of the 1930s as the nadir from which postwar modernism must be evaluated. In fact, with the exception of Roma Termini and the Fosse Ardeatine, all of the architecture exhibited is from the north and east coast of Italy. The enormous body of regime architecture is absent, as are crucial works including the Florence train station, progressive buildings constructed for the New Towns and the vacation colonies, and the Roman post offices by Mario Ridolfi and Adalberto Libera. Huxtable excludes architecture employing vernacular materials such as stone or wood in favor of buildings surfaced in stucco and smooth stone (the Fosse Ardeatine being the exception). Notwithstanding Nervi’s structural bravado, the expressive forms and structural patterns of which (Huxtable suggests) show an ornamental, decorative approach to concrete, Huxtable chose the most abstract examples of Italian design, featuring simple volumes, orthogonal composition, and relentless structural frames. She even describes the postwar departure from the geometric rigor of prewar work as “stimulating and disturbing” for its diversity, although she shows no buildings that illustrate her contention. [21] By highlighting the most compositionally inventive buildings, emphasizing large-scale housing as well as institutional and transportation buildings, Huxtable imposes the legacy of a narrowly defined Rationalism on a narrower selection of postwar projects to create the impression of a formal and aesthetic continuity that was now entering an uncertain phase.

The selections can be partly attributed to Huxtable’s residency at IUAV. Just before her arrival, the school’s rector Giuseppe Samonà had begun assembling an extraordinary faculty: urbanist Luigi Piccinato, architect and designer Franco Albini, urbanist Giovanni Astengo, architect Ignazio Gardella, and historian Bruno Zevi. “Venice School” architects Albini and Gardella feature prominently in The Modern Movement in Italy. Despite his predilections against rationalism and his curious theories of organicism, Zevi’s influence on Huxtable was significant: in addition to introducing her to his history of modernism, published in 1950, he encouraged her to see architecture as the art of space. [22] However, the most critical experience for Huxtable appears to have been the 1951 Triennale di Milano. If the 1947 Triennale, with its focus on housing, economics, and material experimentation, had an urgent, essential tone, it was the 1951 Triennale that broached the topic of reconciliation between postwar democratic Italy and the Fascist entanglements with prewar modernism. In addition to installations that returned architecture to fundamental, transhistorical issues—form, symbolic proportion, light, space, and the human being as the measure of all things—the patrimony of architects who did not survive the war (Terragni, Edoardo Persico, Raffaelo Giolli, and Pagano) was reassessed in the context of the “political difficulties” that cast a shadow over modernism and the ethical obligations of architects. [23] As Ernesto Nathan Rogers later put it, the question of “continuity or crisis?”—would the postwar period require a break with the symbolism, abstraction, and polemics of the interwar era that made architecture so instrumental for the Fascist Party’s program, or could modernism be recuperated and redirected toward democratic, human ends—required looking backward and looking inward. [24] Given that many modernists did survive the war, all of whom had been members of the Fascist Party, and insofar as the monumentalist excesses of the late 1930s and early 1940s offered no viable architectural language for the new democracy, Italian architects during the 1950s struggled with uncertainty about the way forward.

Surveys published in 1954 and 1955 that coincide with Huxtable’s exhibition demonstrate the challenge of reframing Italian design amidst the drive to historicize Fascism. Paolo Nestler’s Neues Bauen in Italien lionizes the Rationalists as engaged in intellectual combat for the renovation of Italian architecture against regressive traditionalists, but concludes that Rationalism for all its strengths neither evolved a uniquely Italian modernism, nor did it vanquish the historicizing tendencies genetic to Italian culture. The images in his book are distant and cold, objectifying buildings to emphasize formal vocabularies and chiaroscuro effects. [25] Carlo Pagani’s Architettura Italiana Oggi begins by lamenting the “political frame” that had been laid over prewar architecture; he then, however, argues that the Rationalists produced high-quality designs that nonetheless failed to improve on their European precedents: instead of being grasped, the opportunity created by the Rationalists slipped away as their increasingly shrill rhetoric linked modernism to Italian tradition in an effort curry favor with the Fascist regime. Focusing on building types and employing images depicting relaxed domestic lifestyles, Pagani’s softer approach to Italian modernism aimed at moving beyond politics rather than asking hard questions. [26] G.E. Kidder-Smith’s 1955 book Italia Costruisce evaluates twentieth-century Italy with an anthropological eye, readily embracing contrasts between abstract forms, material textures, and vernacular profiles. His eclectic survey of buildings and diverse selection of imagery, including urban scenes, landscapes, and public events, situate modern architecture in the climatic and cultural context of Italy. His emphasis on people and place as that which unifies Italian architecture reflects the “continuity” ideology promoted by Rogers, who penned the book’s introduction. [27] All three authors marginalize or even expurge the classicist, monumental projects of the 1930s. However, what Pagani’s and Kidder-Smith’s books demonstrate, and what is absent Huxtable’s show, was the growing use of vernacular forms, local materials, and indigenous tectonics to impart a sense of immediacy and realism, the rise of the Neoliberty style with its eclectic and occasionally medieval allusions, and theories of “preexisting conditions” and the poetics of a sometimes refined, sometimes modest, humble historicism. [28] Taken together, these tendencies underline that the answer to the question “Continuity or discontinuity?” was in favor of the former—in favor of a continuity that could incorporate contradictions, disagreements, and ambiguities, so that architectural culture could move forward while skirting hard questions. Given that nearly every leading architect in the 1950s had been a Fascist Party member or had grown up under the only political system that they had ever known, the incorporation of uncertainties and ambiguities made “continuity” professionally appealing and intellectually expedient.

Whereas this struggle is not overtly depicted in The Modern Movement in Italy, perhaps because Huxtable saw only the first act of a long, complex drama, there is a politics to her selections which reflects some understanding of the rewriting of interwar history that was underway in Italy. Indeed, a simplified variation of the continuity thesis framed her exhibition: “Fine decorative sense, feeling for color, material and pattern, and willingness to experiment and invent have characterized the Italian contribution to postwar architecture and design. This exhibition demonstrates that these qualities stem from a logical and continuing growth during the past quarter century.” [29] However, to focus on her aesthetically sanitized and politically bleached exhibition misunderstands the politics of her show, which is best understood through what is absent. Huxtable’s installation purges architects whose work was tempered by overt allusions to classicism and especially anyone too close to the Fascist Party. She characterizes the Rationalists as victims of Roman academicism which by the 1940s held a “dictatorship” over architectural culture. The most glaring exclusions of architects who were instrumental in the formulation of prewar modernism are of Adalberto Libera, who tarnished his reputation with his design for the partially realized 1942 xenophobic and antisemitic Mostra della Razza (Exhibition on Race), and Luigi Moretti, who was a Fascist deputy and participated in the Republic of Salò, earning him jail time after the war. Some lacunae are difficult to explain, such as Carlo Mollino and Gio Ponti, and the omission of essential Rationalist architects such as Giuseppe Pagano, Mario Ridolfi, and Alberto Sartoris (perhaps the most important Rationalist theorist) is even more perplexing. Other absences reflect Cold War politics: center-left socialist architects feature prominently among the postwar work, but the exhibition includes no designs by architects who were members of or sympathetic toward the Italian Communist Party.

The mission of the Fulbright Foundation, which funded Huxtable’s studies, was to further international educational exchanges that would promote American values and perspectives abroad, while introducing scholars from other countries to the cultural offerings of the United States. While the Foundation was not easily instrumentalized in a direct manner as a propaganda tool, it nonetheless aligned with the US foreign policy goal of encouraging cross-cultural dialogues to counter Soviet propaganda. [30] Monies flowing into the Museum of Modern Art similarly sought to encourage international exchanges that would bolster America’s stature. The Modern Movement in Italy was one of many exhibitions funded by the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation, whose donations to MoMA sought “to encourage the exchange of art exhibitions between the United States and other countries.” [31] As historian Paolo Scrivano notes, Italo-American dialogues around architecture and design made extensive use of exhibitions and publications to build political and cultural bridges. MoMA exhibitions, such as Built in USA were restaged in Italy, while American agencies funded publications, programs, and initiatives related to reconstruction and the reorganization of the architectural profession. Whereas these efforts reflect the aspiration to encourage a liberal, democratic, postwar global order rooted in knowledge, debate, and culture, they never ran afoul of the agenda of blunting Soviet expansion. [32] Although there is no evidence that Huxtable consciously excluded communist architects from The Modern Movement in Italy, their presence, given the order of the world in 1954, would have been as problematic as that of fascists such as Libera or Moretti.

The single-mindedness of The Modern Movement in Italy can be understood as offering an architectural primer that established ground rules for assessing how postwar architects were reconciling the intertwined legacy of Fascism and modernism. Like Nestler’s, Pagani’s, and Kidder-Smith’s surveys, those ground rules began by deciding what and who to exclude for political and discursive reasons. In this regard, this body of work is less about modernism as an object of study and more about the postwar political context of that object. Nestler and Pagani approach the question from a domestic Italian perspective, and both acknowledge the political problems of Fascism in order to quickly move past them. Kidder-Smith and Huxtable view Italy from without, the former adopting an anthropological approach and the latter an art historical one, and both American writers also hasten to set Fascism aside. They all reach the same conclusion: the quality of Italian modernism, while never reaching its full potential, was too significant to be diminished by politics, whereas politics proved much easier to erase. On the other hand, The Modern Movement in Italy demonstrates the many modes in which American political and cultural efforts operated at home and abroad. It was never intended to be a massive retrospective: instead, it was crafted as one of many efforts organized by MoMA, using funds dedicated to encouraging transnational exchanges in order to reinforce geopolitical agendas. Given that the show was designed as an instrument of education rather than a critical retrospective of Italian architecture, Huxtable’s curation takes on a different light.

Curating can sometimes be understood as an art of exclusion—an art that is as much about technique as it is about communication and politics. If read in the context of Ada Louise Huxtable’s storied career, her selections for The Modern Movement in Italy are myopic: she misrepresents the 1930s and addresses none of the pressing social and human issues that were churning Italian society in 1954. In the context of the history of MoMA her show deserves better than to be entirely forgotten, but perhaps merits little more than a footnote or a few sentences. Huxtable’s exhibition is more meaningfully understood in the context of the postwar international stocktaking of Italian modernism. The Modern Movement in Italy coincided with a moment that was both fecund and fraught. It was fecund because, in a few short years between 1949 and 1955, there were countless retrospectives, exhibitions, and books reevaluating modernism’s legacy and its uncertain postwar trajectory. It was fraught because the field was oversaturated and therefore hard to stand out from. The nuances and uncertainties of Italian postwar architecture did not translate easily into the straightjacket of an exhibition.

The issue in the postwar stocktaking of Italian modernism was whether this movement had traits and characteristics of intrinsic value that could serve as the basis for a continued postwar modernism, free from the taint of Fascism. This stocktaking, which addressed both domestic and international audiences, always involved politically driven choices of what was to be excluded, forgotten, or erased. Unlike Germany, where much architecture was destroyed, most of Italy’s fascist-era buildings remained standing after the war. Publications, histories, and exhibitions became the chief means, through curation as exclusion, of constructing alternative histories and narratives that diminished, marginalized, or recast these monuments and architectures even as they continued to be used as functional buildings. Huxtable’s exhibition, with its limitations and distortions, underlines how the politics of continuity required a parallel program of erasure and forgetting, one that, for all its uncertainty, proved to be convenient, instrumental, and, indeed, essential, in both Italy and America.