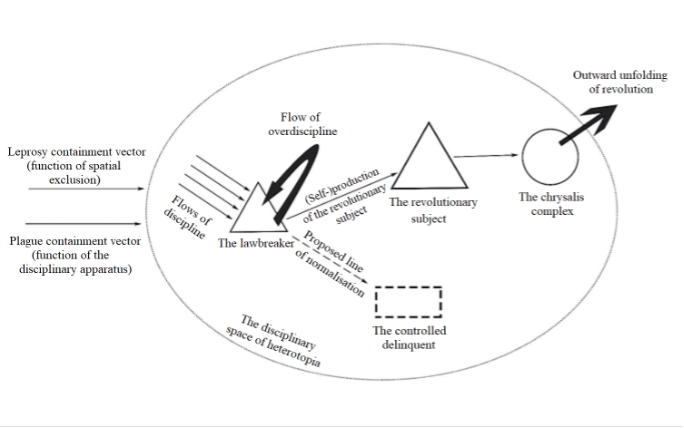

The machine of (self-)production of the revolutionary subject in a disciplinary space

What does a national museum have in common with a prison for convicts sentenced to penal servitude? Thanks to Michel Foucault, we know that both are disciplinary spaces which recapitulate the containment of leprosy and plague. They combine the spatial exclusion of lepers with the apparatuses of cellular [1] discipline in plague-stricken spaces: “The leper and his separation; the plague and its segmentations.” [2] In the late eighteenth century, the liberal philanthropist Jonas Hanway formulated the concept of the “reformatory” upon which such spaces were based: here, the individual is reformed, being made subject to transformation. [3] According to Hanway, responsibility for the work of transformation falls upon the individual themself, but this occurs under the conditions of spatial isolation into which society has forced him or her. The reformatory is a special space set up to correct the individual according to certain established narratives. In prison, penal servitude or exile, one must suppress the delinquent [4] within oneself—that is, the criminal—and become a “normal”, law-abiding citizen. In a national museum, meanwhile, all works of art must be arranged in accordance with the history of the nation state, thereby once again involving the disciplining of oneself and of all visitors by means of a corresponding narrative.

However, as Pyotr Kropotkin and Michel Foucault demonstrated, prisons did not reform individuals; on the contrary, they were universities of crime, producing delinquency as a social stratum through which heterogeneous and chaotic illegality could be controlled. On the eve of the October Revolution, the revolutionaries of tsarist Russia exploited this “dark” side of the prison apparatus—they transformed prison into an institution for the creation of a mass revolutionary class, combining the prison’s mission of producing and perpetuating delinquency with their own revolutionary goals. The tsarist system of “prison, penal servitude and exile constituted, from 1905 to the February Revolution of 1917, a vast laboratory, a supreme revolutionary school where revolutionary cadres were successfully prepared.” [5] Ultimately, the political prisoners who were drawn to Moscow from across Siberia by the summer of 1917, having been released in March by decree of the Provisional Government, came to form the backbone of the subsequent revolution in October—alongside their comrades who had returned from exile abroad. At the Eighth Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) held in 1919, 184 of the 305 delegates attending had personal experience of penal servitude or exile (making up a total of 315 years of imprisonment between them). [6] The disciplinary apparatus had been subverted, or, more accurately, “redisciplined”, and simultaneously strengthened by its own objects from within, so that the flow of (self-)discipline was redirected toward the education of the revolutionary subject.

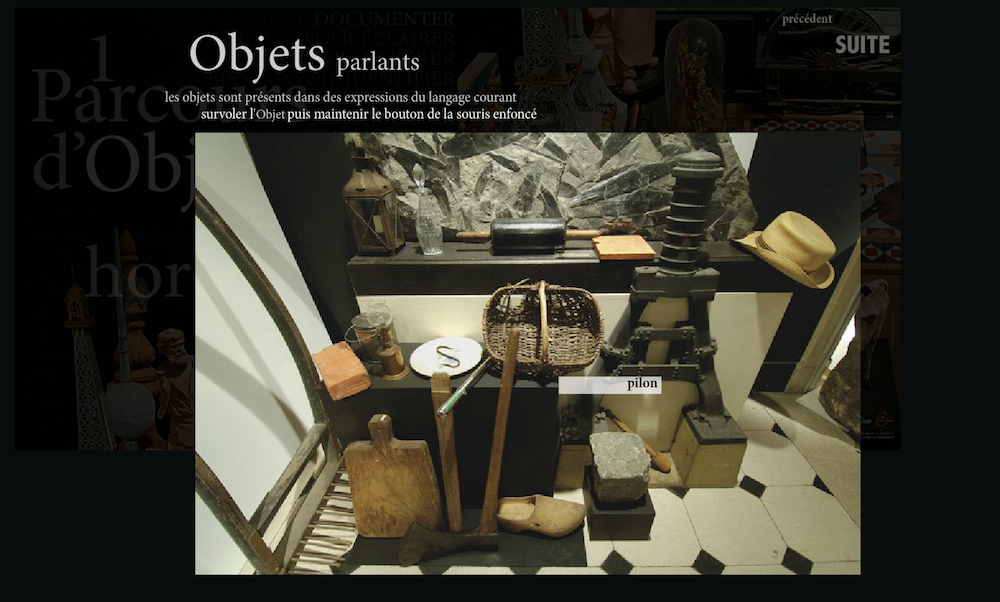

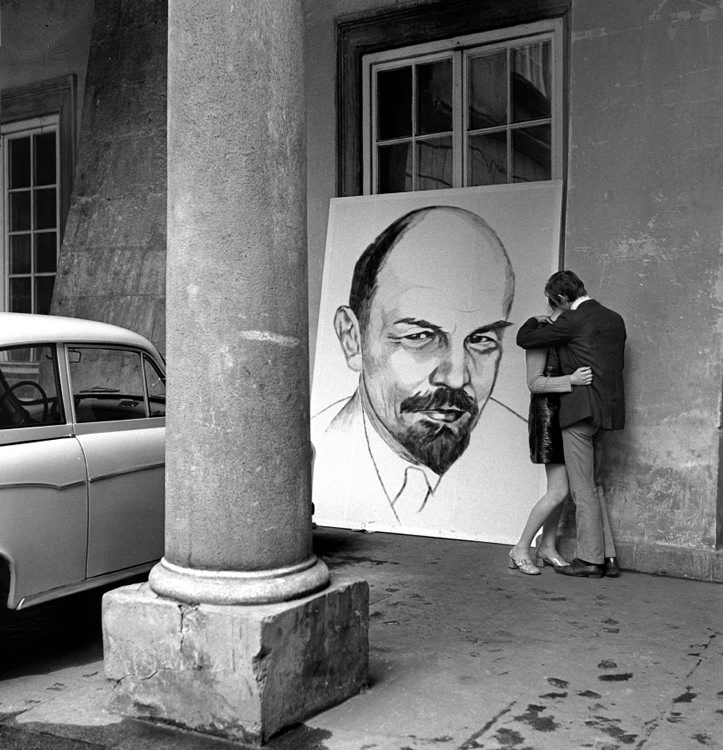

A museum can likewise, according to Boris Groys, act as a “cradle of revolution”. To change the world, a meta-position must be taken in relation to it, and a historical artefact in a museum can provide just this. After all, despite the fact that “these objects from the past—seen in the here and now—belong to the contemporary world, they also have no present use.” [7] Objects from another time or another world are capable, through their very presence, of changing the time and world in which they are placed. These defunctionalised objects exist outside the logic of everyday “utility”. By virtue of their presence, they point to the possibility of recoding and recreating the world whose logic they negate. Moreover, in some sense, objects of this nature make such recoding inevitable, and therefore, from the perspective of existing normative laws, they can be perceived as “demonic”.

Yet such an object does not function or even exist in isolation. It is first of all part of a machine composed of the artefact and a heterotopia—the museum space that brings about its defunctionalisation. Secondly, in order to begin working, this machine must be connected to a viewer. And not just any viewer, but one willing to perform a reenactment, that is, the reconstruction of the cultural imagination hidden within the artefact. Certain hopes and aspirations have been stripped away from modernity, but they did exist in the time the object bears witness to, and the viewer, desiring their return to the present world, reconstructs them in their imagination. Marx, for example, wrote that the French Revolution had taken inspiration from the republican traditions of Antiquity. Groys, meanwhile, suggests examining avant-garde works of art and reviving their inherent logic of defunctionalisation, which they had once implemented, by reducing art’s informational function.

Thus, an object encoded with another cultural imagination, when hooked up to a heterotopia and a viewer desiring reconstruction, constitutes a machine for the (self-)production of the revolutionary subject. It functions, it is productive, and it even abides by the prescribed Law in the sense that it acts according to instructions, or, rather, according to its own specifications—a museum visitor contemplates an artefact on display, while prisoners in a penal colony undergo transformation. But at the same time, this machine “rewrites” the words of the Law and “relabels” them according to its own pattern, redirecting the subject’s production in an unforeseen course.

There are complications here. First of all, the subject may desire the coming to fruition of a conservative revolution. This is precisely how Deleuze and Guattari, following Wilhelm Reich, explain fascism—it was produced by multiple desires, not prescribed at the secondary level of ideology. [8] Second, in proposing that the reconstructed imagination be divided into “revolutionary” and “reactionary” as “good” and “bad”, we thereby prescribe a new law, which at a certain point risks becoming repressive.

This difficulty can be resolved by translating the concept of “revolutionary” to the meta-level. Then it will signify not the imagination of specific models—for example, a republican form of government in an authoritarian society—but rather a reenactment of the very logic of defunctionalisation, that is, the procedure for recoding any prescription, any law. Groys sees precisely this kind of experimentation in works of the avant-garde: the very logic of “cutting away” from the normative surface must be reconstructed, regardless of its many specific historical forms—defunctionalisation as a conceptual gesture—so that it can be revisited again and again in constantly changing conditions. This is a formula for permanent revolution, which also presupposes, among other things, a revolt against the state produced by a victorious revolution—a formula that seeks to reassemble any law, only to further reassemble it anew, over and over again.

We thus have two modes of operation for the reformatory’s complex of overdisciplinary [9] recoding, resulting in the (self-)production of the revolutionary subject. The difference in these modes is linked to what becomes fixed as a result of recoding: a specific social model or the logic of defunctionalisation and recoding per se. In any case, the complex is realised as a synthesis of “demonic” relics (objects that are bearers of a different cultural imagination), a heterotopia, and the willing subject. To give an example, the demonic relic for the revolutionary subject on the eve of 1917 was Marxist theory, contained in books and people’s memories, while the heterotopia was the space of a penal institution, and the willing subject was the individual and/or collective of political prisoners. As noted above, it is of importance that such a machine can operate in different directions and may produce not only a socialist society but also, for example, fascism. At issue is not so much whether one is good and the other bad, but rather that, ultimately, the prospect inevitably arises of fixing the result as a new prescription. This may be called the first mode of operation of the complex. The question therefore arises of producing a metarevolutionary subject who studies the very logic of defunctionalisation, that is, programs himself as one who, under any conditions, facilitates the advent of the External—in all its historically changing guises. This is how the second mode operates. Such a subject is possessed of heterotopic optics (not placing any specific heterotopias, even the most progressive ones, at the centre); he is able to look at reality outside the dominant narratives and, under any conditions, produces genuine difference.

These two modes are ever present and mutually antagonistic. Any revolutionary subject simultaneously (self-)produces a new law, a new repressive surface for fixing the result, and a corresponding desire. However, alongside this, there is always what Edward Soja has referred to as “Thirdspace”, and what Deleuze and Guattari call a polysemantic or nomadic conjunctive synthesis: a non-dual logic or the perspective of and/both together, which struggles with the surface of registration, that is, with the fixation of the conquests of the revolution. [10] This is not a different revolutionary subject, but the same one, albeit understood and reassembled in a somewhat different manner. And although the question of the difference between the two modes was clearly posed only in the second half of the twentieth century (as, for example, by Deleuze and Guattari in Anti-Oedipus), their conflict long predated this. In particular, following the October Revolution, the heterogeneous Society of Former Political Prisoners and Exiled Settlers (Obshchestvo byvshikh politkatorzhan i ssylnoposelentsev, usually abbreviated, as hereinafter, as OPK) came under increasing repression from the increasingly powerful central government. The conceptual struggle consisted of opposing revolutionary ethics to the desire to secure the gains of the Revolution.

“Converting” the machine of subjectification: Recoding flows and practices of the self

The role played by tsarist penal colonies in the October Revolution was explored in the 1920s, within the framework of intellectual activity supported by the Society of Former Political Prisoners and Exiled Settlers (OPK). The OPK’s chief printed publication, the journal Katorga i ssylka (‘Penal Servitude and Exile’, 1921–1935), focussed on collecting and publishing the personal memoirs of the former political prisoners who comprised its membership. This served as the basis for conceptual generalisations about the central role penal servitude and exile had played in the Revolution. The main ideologist was Vladimir Vilensky-Sibiryakov, who in 1923 called the tsarist penal system “the Romanov University” and a “school of revolution”. In his own words: “After 1905, against the will and desire of tsarism, … the institution of political penal servitude and exile was transformed into a vast political school for the training of those cadres of the 1905 revolution who had ended up thronging the prisons, penal colonies and exile.” [11]

In 1928, Sergei Shvetsov published a series of articles in Penal Servitude and Exile entitled “The Cultural Significance of Political Exile in Western Siberia”, highlighting the following positive aspects: scientific exploration of the region, development of the local press, medicine, and culture, and public education and revolutionary work. According to Shvetsov, “the imprisonment and exile of that time represented unique oases of freedom of speech, if not in print, then at least in the spoken word” (No. 11, p. 97); They spread “Senichka’s poison… [12] which so imperceptibly, but persistently undermined the roots of tsarist autocracy” (No. 10, p. 101), the fruits of which included “the rebirth… of some ordinary inhabitant of Surgut [a small town in Western Siberia]” (No. 10, p. 112) in an anti-tsarist, revolutionary spirit.

Here we are dealing with two distinct but interconnected vectors of recoding. Shvetsov is writing about how the political exiles transformed the local context, while Vilensky-Sibiryakov argues that prisoners transformed and strengthened themselves in the revolutionary spirit. In the first case, the flow of discipline is directed outward, in the second, inward. Or: in the first case, we have the Decembrist exile, while in the second, we have the model that emerged after 1905, when the penal colonies were filled with poorly educated workers, peasants, and townsfolk, many of whom then transformed from casual opponents of the regime into convinced and unyielding revolutionaries. In the second case, the hermetic confinement of imprisonment was used to construct a machine for the (self-)creation of a collective revolutionary subject, with the future expansion of this subject being teleologically embedded in the process of transformation. This process can be divided into a hermetic stage of transfiguration (internal revolution) and a delayed stage of outward expansion (external revolution), the result of which was destined to be the rebirth of the whole world. To borrow an image from developmental biology, one might say that the semi-conscious “revolutionary larvae” of the pre-prison period pupate in a penal ward, transforming into a cocoon or chrysalis of revolution, from which, in due course, a full-fledged form would inevitably emerge—the Revolution itself.

This is precisely the model advocated by Vilensky-Sibiryakov, and was confirmed after the fact by numerous testimonies: “the simple accumulation of knowledge was not what we needed … but rather to emerge from prison … as someone who could contribute greatly to the revolutionary movement with his knowledge,” [13] “in penal servitude… the cadres of the revolution were forged,” [14] “even in penal servitude, the revolutionary remembered that he was a foot soldier of the revolution, temporarily captured, obliged always and everywhere to arm himself with the weapons that would bring him victory: literacy, knowledge, and the ability to analyse reality from a class perspective, from the perspective of revolutionary Marxism”. [15] The experience of the past was reinterpreted, and tsarist imprisonment now appeared as an absolutely vital stage in the revolution: “Where else would I have found at that time such opportunities for a Marxist education as prison afforded me?” [16] This last assertion is not as naive as it may seem. After all, the machine of (self-)creation of the revolutionary subject emits a flow of overdiscipline, and this in the sense that prisoners might even strengthen the discipline of the reformatory, while recoding its work in a different direction. The principle remains, the machine functions smoothly, but the direction is changed.

According to Foucault, the prison system of punishment as a machine for transforming prisoners emerged in the nineteenth century. Previously, the authorities had not sought to reform the punished—the punishment system not having been penitentiary in character (from the Latin poenitentia, meaning “repentance”). The new system represented an “assemblage” of practices: in particular, the dual semiotic technique of punishment, deriving from the ideologists of the Enlightenment. It was dual because, firstly, the very point of application of power had shifted: it became “the ‘mind’ as a surface of inscription for power”. [17] Secondly, the punished individual was expected to labour for the common good—to teach a useful lesson by example, and to participate in the production of discourse: “The publicity of punishment … it must open up a book to be read”, “the punishments must be a school rather than a festival; an ever-open book rather than a ceremony”. [18] And the inmates of Russia’s penal system on the eve of 1917 fulfilled these semiotic demands with a vengeance: they were indeed busy producing knowledge, discourse, and a lesson for all, but it was not that lesson. The lesson taught was quite another—one that affirmed not the established law, but a new, subversive codex.

The second lineage in the penitentiary system’s pedigree, according to Foucault, derived from Protestant ethics and their notions regarding discipline of the body for the sake of transformation of the soul. The monastery, the religious brotherhood, the asylum, the workhouse, and now the prison: “solitary work would then become not only an apprenticeship, but also an exercise in spiritual conversion”. [19] The functions derived from these two genealogical lines—the semiotic and the transformative—were reflected in the new politics of the body that were adopted by the disciplinary institution of the prison in the nineteenth century.

In any disciplinary space, powerful disciplinary flows are directed at those found within. Just as the application of discipline proved to be a key “technique for the production of useful individuals” in the 1800s, so the spaces of disciplinary institutions, including prisons and museums, emerged as machines for the implementation of these techniques of subjectification. For the subject is not only one who thinks, as opposed to the inert dimensionality of objects; it is also one who is “subjectivised”, that is, shaped by the flows of power. Not only one capable of activity and knowledge, but also one who is subject—literally “lying beneath” or”subordinated”: a duality which is evident in the English word “sub-ject.” Therefore, the individual who finds himself within a disciplinary space—this specially constructed machine—is doomed to subjectivation. The vector of this subjectivation is not so immutable, however—it turns out that it can be adjusted: one can introduce one’s own pattern into the disciplinary flows, and subjectivation can be accomplished in a different manner than expected.

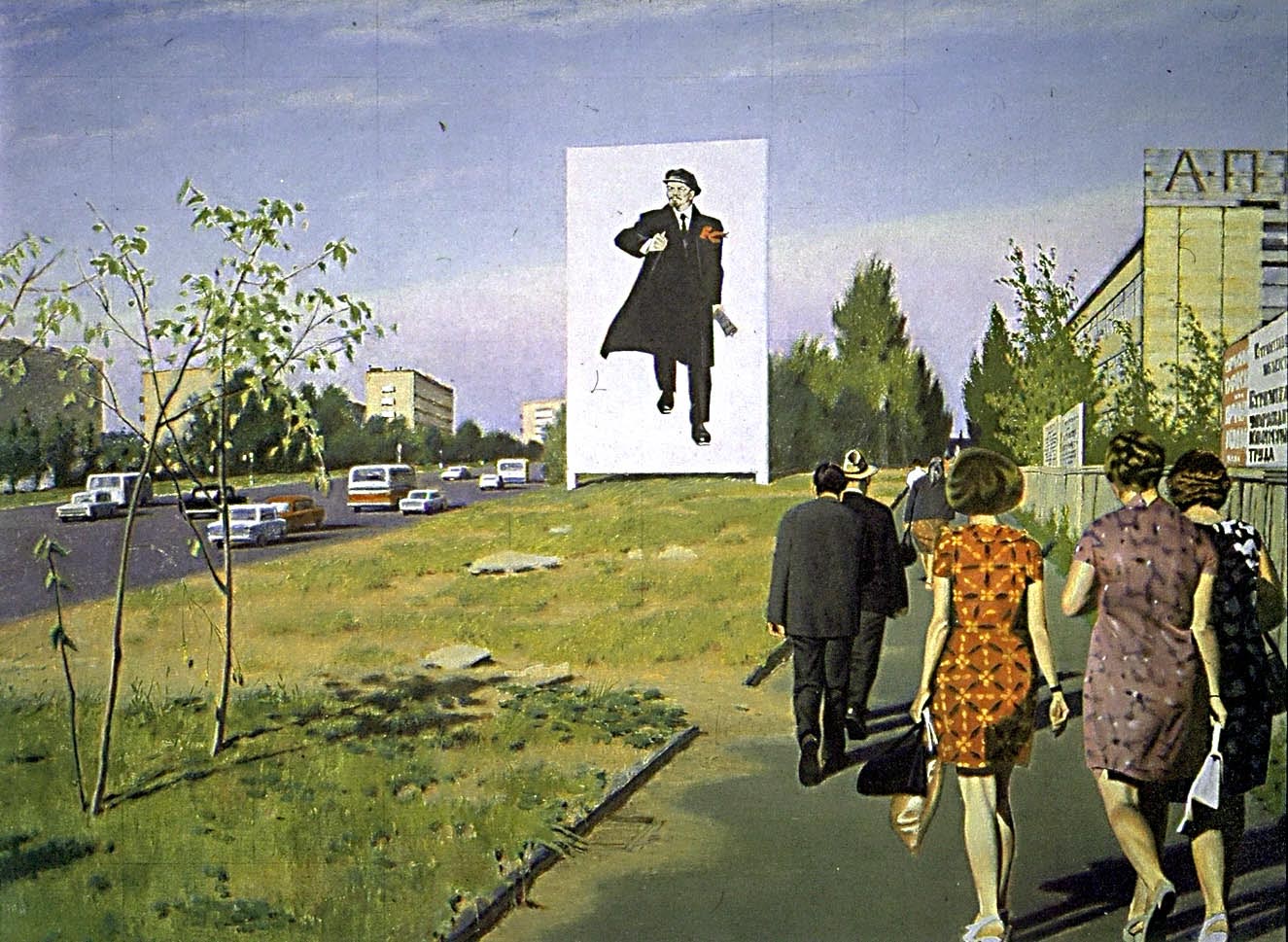

This is possible precisely because the transformation occurs within the individual. The “terrible secret” of disciplinary spaces is that the subjectivation they produce is, to some extent, always a “practice of the self”, as the late Foucault called it. And it is exactly at this point that the potential lies for the individual’s “conversion”—just as Saul the militant Pharisee was converted and became the Christian Paul. Subjectivation is the exercising of power, but this can involve both external power (the codex) and internal power (power over oneself). The Ancient Greek model of subjectivation, which Foucault proposed as a useful practice, presupposes the attainment of freedom solely through power over oneself. The law emanating from oneself must be distinct from the external lawcode and more intense than it, that is, it must constitute overdiscipline. This feat was successfully mastered by political prisoners in Russia’s penal system on the eve of 1917; according to Groys, it should be practised in museums, contemplating avant-garde works within the disciplinary currents of art history.

The chrysalis complex: Heterotopia and the island

“Converting” the subjectivation machine is inseparable from the production of the “converted” subject. But at what point does the product of local labour, carried out in the heterotopia of a disciplinary space, become the “chrysalis” of a coming universal rebirth? This transition is clearly not to be found in the nature of disciplinary production or its objectives—these do not entail any transformation of society as a whole. However, a closer look reveals the religious (and therefore potentially eschatological and messianic) components to this process, conditioned by its Protestant genealogy: “the idea of an educational ‘programme’ … first appeared, it seems, in a religious group, the Brothers of the Common Life”. [20] It may be assumed that the task of universal transformation is posed not by the form, but by the content of the flows of transdisciplinary recoding: if we (self-)create a revolutionary subject, then he or she will inevitably be aimed at deploying the revolution outward. This holds true, but the chrysalis complex also arises structurally—through the spatial logic of the disciplinary apparatus, structured as a heterotopia and as an island.

Heterotopias are “spaces, which are in rapport in some way with all the others, and yet contradict them”. [21] This is Michel Foucault’s classic definition of 1967, but let us turn here to biology, from which the philosopher himself drew this concept. According to Ernest Haeckel, during the formation of an embryo, a particular organ or region can begin to develop either at a different pace (heterochrony) or in a different space (heterotopy): this leads to an ontogenesis (individual development) that deviates from phylogenesis (the development of a biological species). As a result, recapitulation (the reproduction of biogenetic law) fails: new traits emerge, which can then become fixed. An example is provided by the long neck of the giraffe, which arose as a result of heterochrony—an extended development period of the seven cervical vertebrae. In heterochrony, the development of a certain part of the organism is temporally shifted (that is, it occurs faster or slower than prescribed by law), while in heterotopy, it is shifted spatially (that is, it occurs in the wrong place or direction). This implies a greater innovative potential for heterotopy: “Heterochrony is of interest in part because it can produce novelties constrained along ancestral ontogenies, and hence result in parallelism between ontogenesis and phylogeny. Heterotopy can produce new morphologies along trajectories different from those that generated the forms of ancestors.” [22]

Unlike heterochrony, heterotopy creates a form that is not similar but entirely different, and is therefore more revolutionary. Groys analogously distinguishes between reactionary and progressive work with the cultural imagination hidden in the artefacts of the past: the former affirms dominant forms by finding their “sources”, while the latter produces a form that is novel to the present. In biological terminology, the former asserts a theory of recapitulation, while the latter gives rise to a branching phylogenesis. The advantage of heterotopias in terms of the production of differences is clear: moving in the opposite direction is potentially more fruitful than outpacing others. This is precisely why the strategic “spatial turn” in knowledge production, as proclaimed by Foucault, is so important. However, things are somewhat more complex than this, and we are always dealing with a combination: heterochrony and heterotopy together lead to a break with normative reproduction. To understand the process of difference production, “we need compasses … as well as clocks”. [23]

The analogy between organism and society is purely phenomenological: both are pseudo-unities formed in accordance with a certain law that prescribes the relationships between parts and the whole. If a new section is produced, the pseudo-unity that includes it does not transform the remaining sections according to a new pattern, but reconfigures all internal flows and relationships. Thus, the elongated neck does not swallow up all other organs, though all parts of the organism, like the organism as a whole, respond in someway to this change. The task of the production of differences, so central for Foucault, presupposes the constant diversification and differentiation of the entire field through numerous heterotopias. It is in this sense that heterotopia proves to be the chrysalis of universal revolution—through the inevitable transformation of the whole in complex correlation with the new organ. The non-standard spatial change of a single part during ontogenesis leads to changes in the entire species through the consolidation of this change. In this sense, the (self-)produced subject is bound to turn outward and influence society—by the simple fact of its existence being included in the general mechanics.

However, the chrysalis complex functions not only as a heterotopia but also as an insularity (from the Latin insula, “island”). The insular thinking of the Modern Era assumes that a certain isolated entity, or “self”, is capable of reformatting the entire world in its image, and, moreover, sets its sights on doing so. Antonis Balasopoulos, a scholar of island geopoetics, defines this as the insular institution of colonial modernity [24]: the island not only turns out to be the ideal colonial possession but also the ideal metropolis. An island/empire dialectic emerges, according to which the machine of insularity operates. The “noman’s land” of a “desert” island is always an invitation to (re)create the world in a potentially more successful “second” attempt. [25] In this sense, people seek out “desert” islands as a space in which to work out a model for restarting the world. We are no longer entirely comfortable with this eschatological horizon of the Modern Era colonial machine, but the realisation of the chrysalis complex is always something deferred, while difference or another space is produced here and now.

The chrysalis complex is thus a combination of heterotopia and insularity. Heterotopia alters the internal relationships of pseudo-integrity in the here and now through the formation of a new element within it, while the logic of insularity presupposes a deferred universal transformation according to its own model. The latter is nothing other than the expansion of a newly produced law, and therefore carries with it the inevitability of betrayal of the heterotopic optics.

The Museum of Penal Servitude and Exile

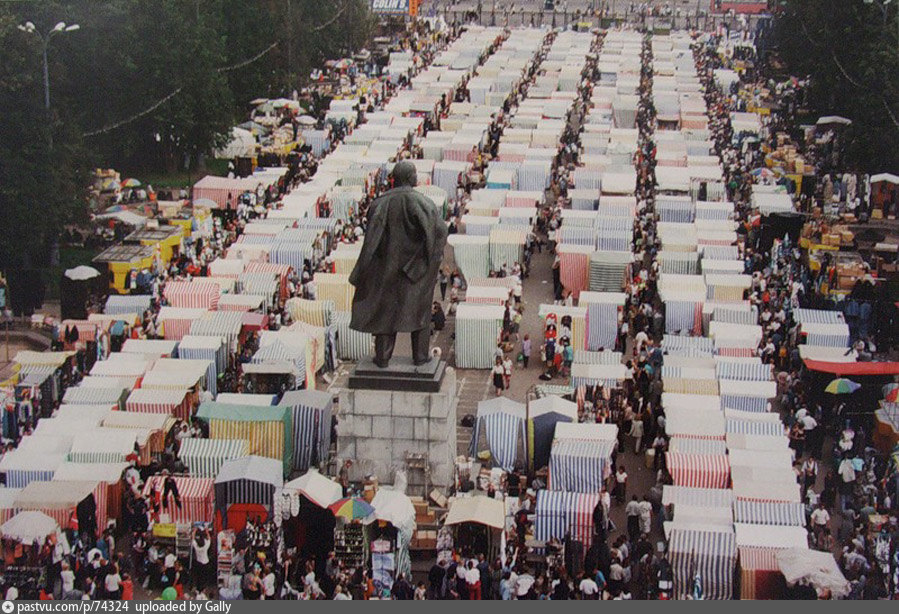

The members of the OPK (the Society of Former Political Prisoners) possessed “dual citizenship”—not only of the USSR, but also of an imaginary topos—the tsarist prison, which would for many of them gradually merge with the image of newly realised Soviet prisons. When filling out the admissions form, the anarchist Olga Taratuta thus gave “Butyrka Prison” as her “place of residence”—having by this point served fourteen years in pre-Revolution prisons and four months in the Soviet Butyrka. [26] Alongside the Bolsheviks, the OPK’s membership included many former Narodnaya Volya (“Will of the People”) members, anarchists, Bundists, Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs) and Mensheviks. It had therefore been desirable to set up the Society as a “non-partisan” discursive space, not only for alternative socialist forces (the push from below) but also for the rapidly strengthening central government—as a means of control (the push from above). So, in spite of the fact that the initiators of the OPK were the anarchists Pyotr Maslov and Daniil Novomirsky, the initiative was supported by the elite of the RKP(b) (the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)): Soviet trade union leaders Mikhail Tomsky and Yan Rudzutak secured state funds for this purpose, enlisting the support of the Secretary of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, Avel Yenukidze. All of them, except Yenukidze, had been incarcerated together in Moscow’s Butyrka prison in the 1910s. However, “in supporting the founding of the OPK, Tomsky primarily sought, through an organisation that though separate was linked by personal ties to the Party, mechanisms to control, and eventually politically integrate or neutralise, the socialist and anarchist forces that could not be persuaded to join the RKP(b).” [27] In this sense, the OPK functioned as a deviant heterotopia, proving to be a machine for producing and containing controlled deviations (compare this with the production of “delinquency” in the prison). Conflict was thus inherent from the very beginning and manifested itself as early as the OPK’s founding meeting in 1921, at which the SR Mikhail Vedenyapin was arrested.

The OPK was founded in 1921 on the principle of “non-partisanship” or “active neutrality”, with an implied, but not formalised, loyalty to the Bolshevik line. [28] Naturally, this reflected the OPK’s programmatic lack of a unified political will, which presupposed the coexistence of its members’ diverse and irreducible individual positions. A shared past as political prisoners, that is, a commitment to the revolutionary ethic, served as their unifying element. However, as early as 1922, the society faced the threat of closure due to having Left SRs among its members, as well as its support for political prisoners in Soviet prisons, resulting in persistent demands for the society’s “communisation”. In 1924, the OPK was reorganised: the general meeting was replaced by an all-Union congress (which meant replacing broad democracy with the institution of representation), the Communist faction gained control of the leadership, and the laws of the Soviet state were officially elevated above revolutionary ethics—one’s merits in the pre-Revolution period ceased to be a significant criterion for admission to the OPK. Most members of non-Bolshevik parties were expelled from the Council (the executive body of the OPK), and the pro-Narodnaya Volya moderate Bolshevik Ivan Teodorovich was replaced as chairman by the more radical Vladimir Vilensky-Sibiryakov.

Though the principle of “non-partisanship” was effectively dismantled at the level of official rhetoric and the society’s leadership, it continued to be implemented in the institution of OPK regional associations, established in 1923. [29] Many figures expelled from the central bodies of the OPK, as well as outside specialists, found employment in these associations, forming a peculiar kind of “democratic forum”. [30] Paradoxically, it was at this point in time that the OPK began to develop the theory about the tsarist prisons having played a central role in the 1917 Revolution. This presupposed the heterogeneity of the revolutionary subject, which sooner or later was bound to conflict with the idea of the Bolsheviks having been the leading revolutionary force. Once that point was reached, the OPK was “shut down” as an active political heterotopia in the present, but remained so in relation to the past, implementing heterotopic logic in its discursive space—in the journal Katorga i ssylka (“Penal Servitude and Exile”, hereinafter “KiS”) and the museum of the same name.

On the pages of KiS, Vladimir Pleskov, a critic of Soviet repressions against political prisoners and a former Menshevik, wrote articles about the Socialist Revolutionaries Yegor Sazonov and Maria Spiridonova (Issue No. 1); former Narodnaya Volya member Mikhail Frolenko wrote about Nikolai Chaikovsky’s Godmanhood concept (No. 5 (26), 1926); and the mysticist anarchist Georgy Chulkov wrote about the utopian socialism of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and the followers of Petrashevsky (No. 2 (51) and No. 3 (52), 1929). In 1929, on the initiative of Ivan Teodorovich, the magazine hosted a discussion about Narodnaya Volya; texts were also printed in various years about the “Russian Jacobins” Pyotr Zaichnevsky and Pyotr Tkachev, about Militsa Nechkina’s Society of United Slavs, about the Vertepniki – members of the circle that gathered around Pavel Rybnikov, including the Slavophile Alexei Khomyakov and the Old Believer arts patron Kozma Soldatenkov, about Makhayevshchina (“Makhayevism”)—the anti-intellectual theory of social revolution—and much more.

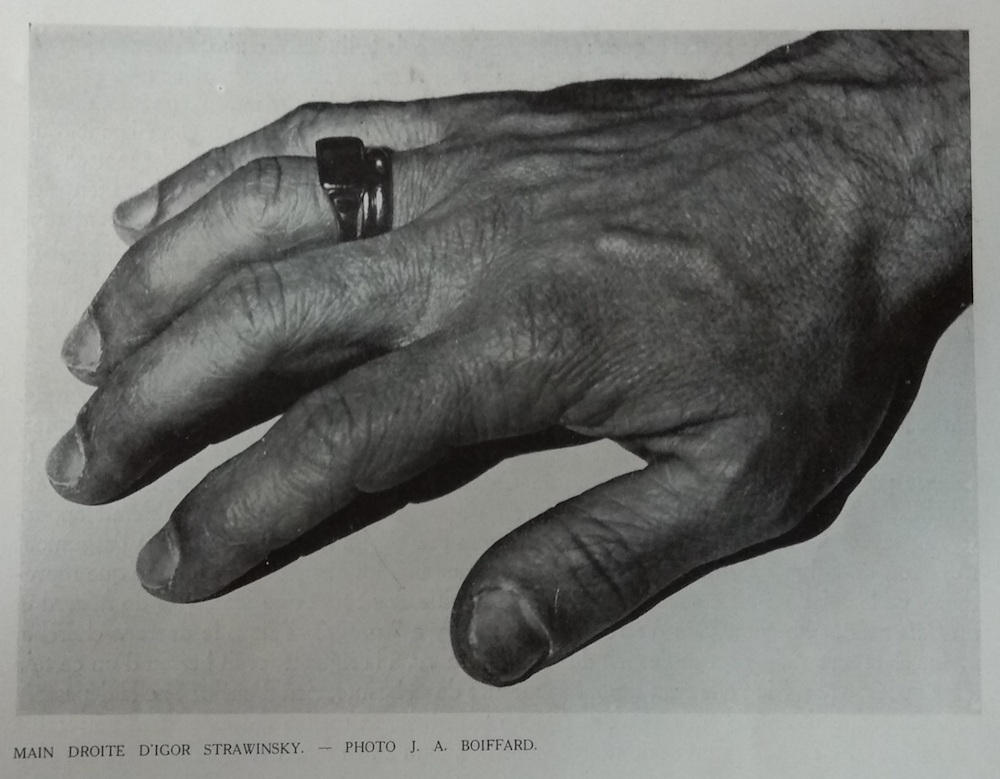

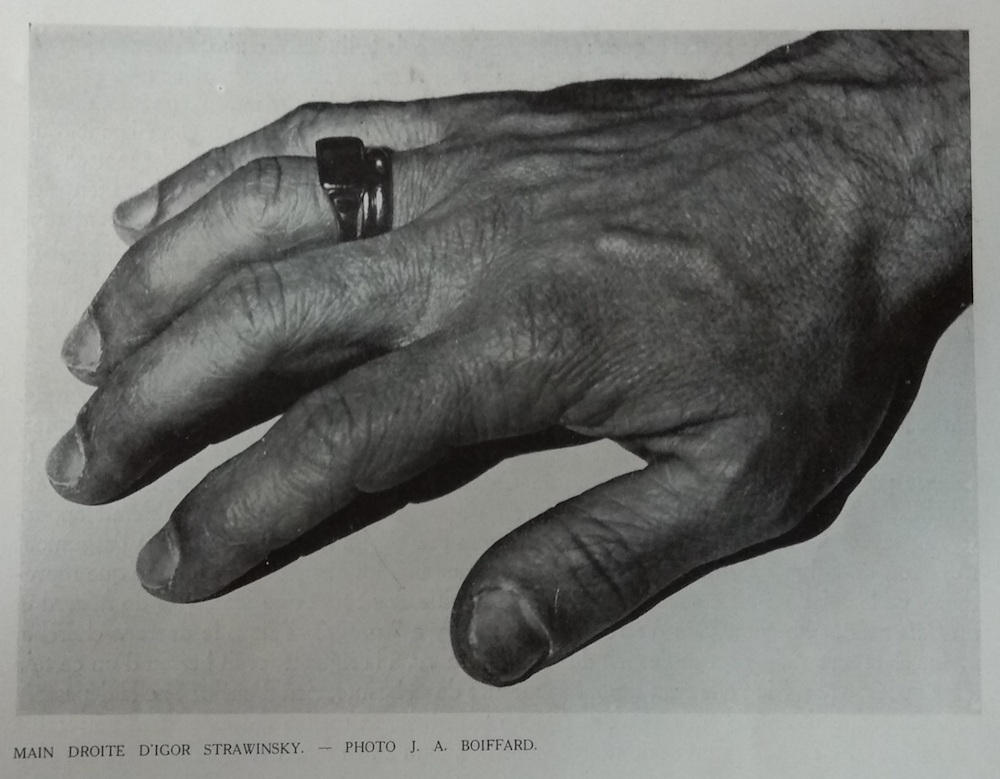

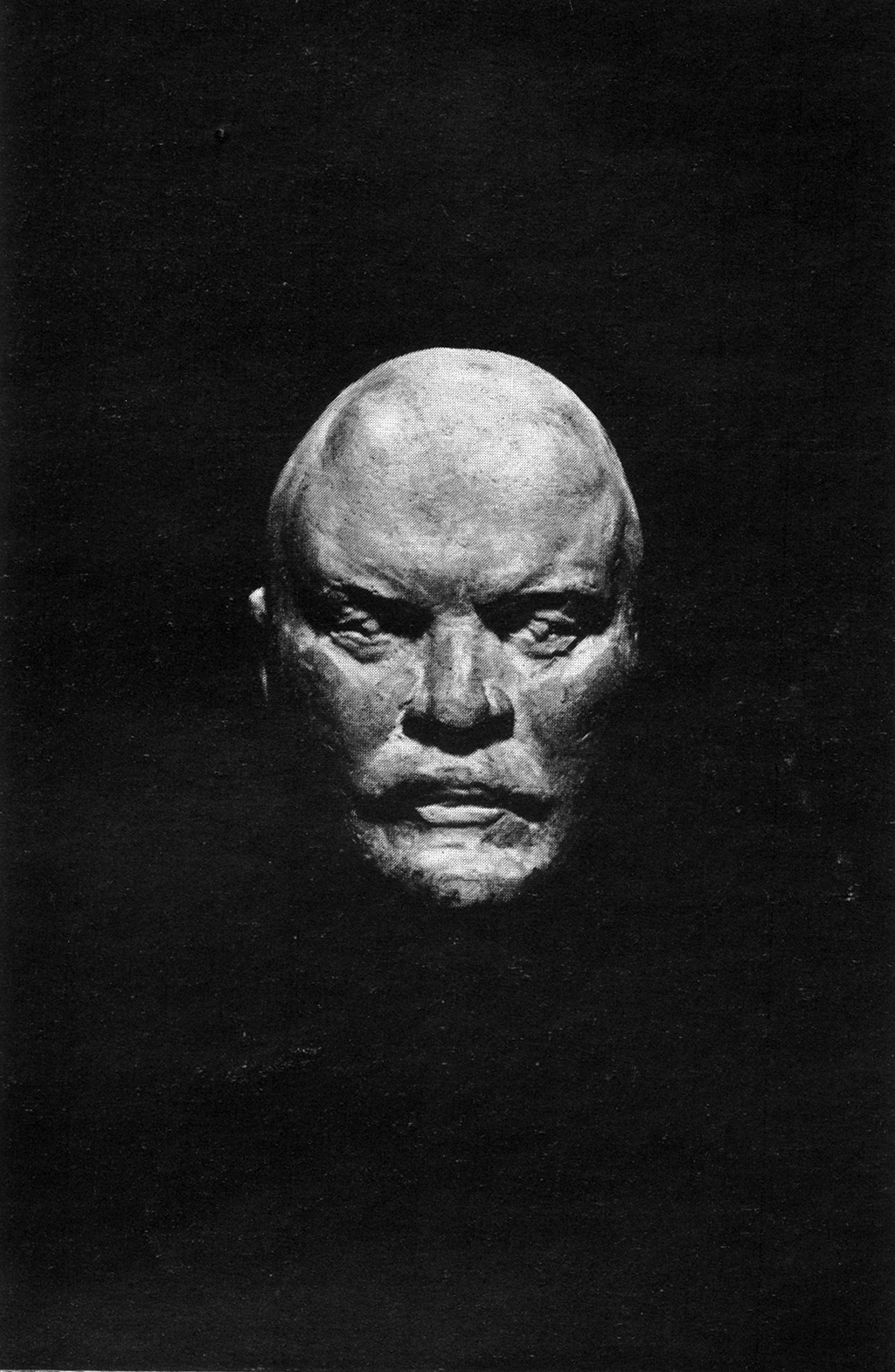

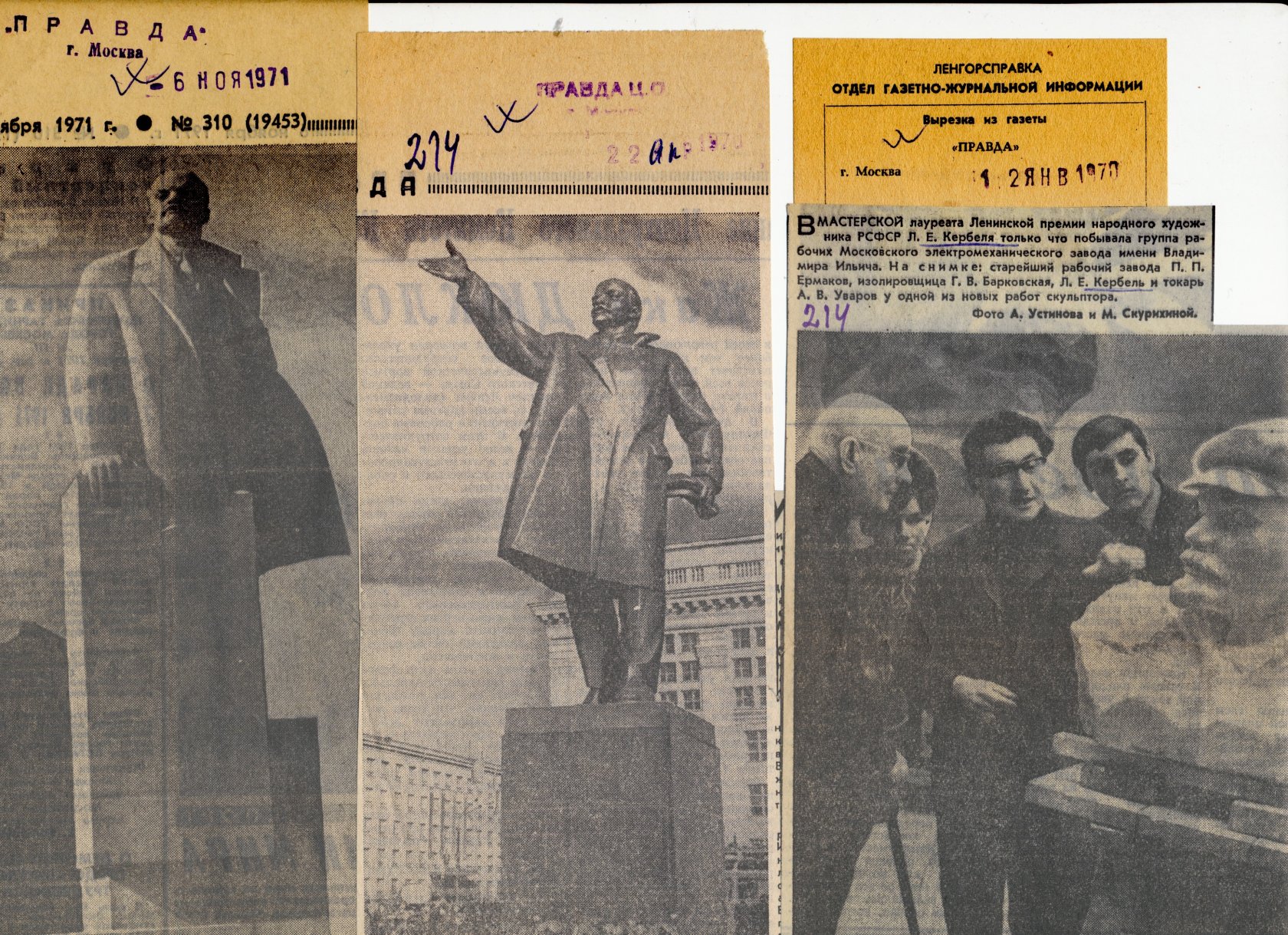

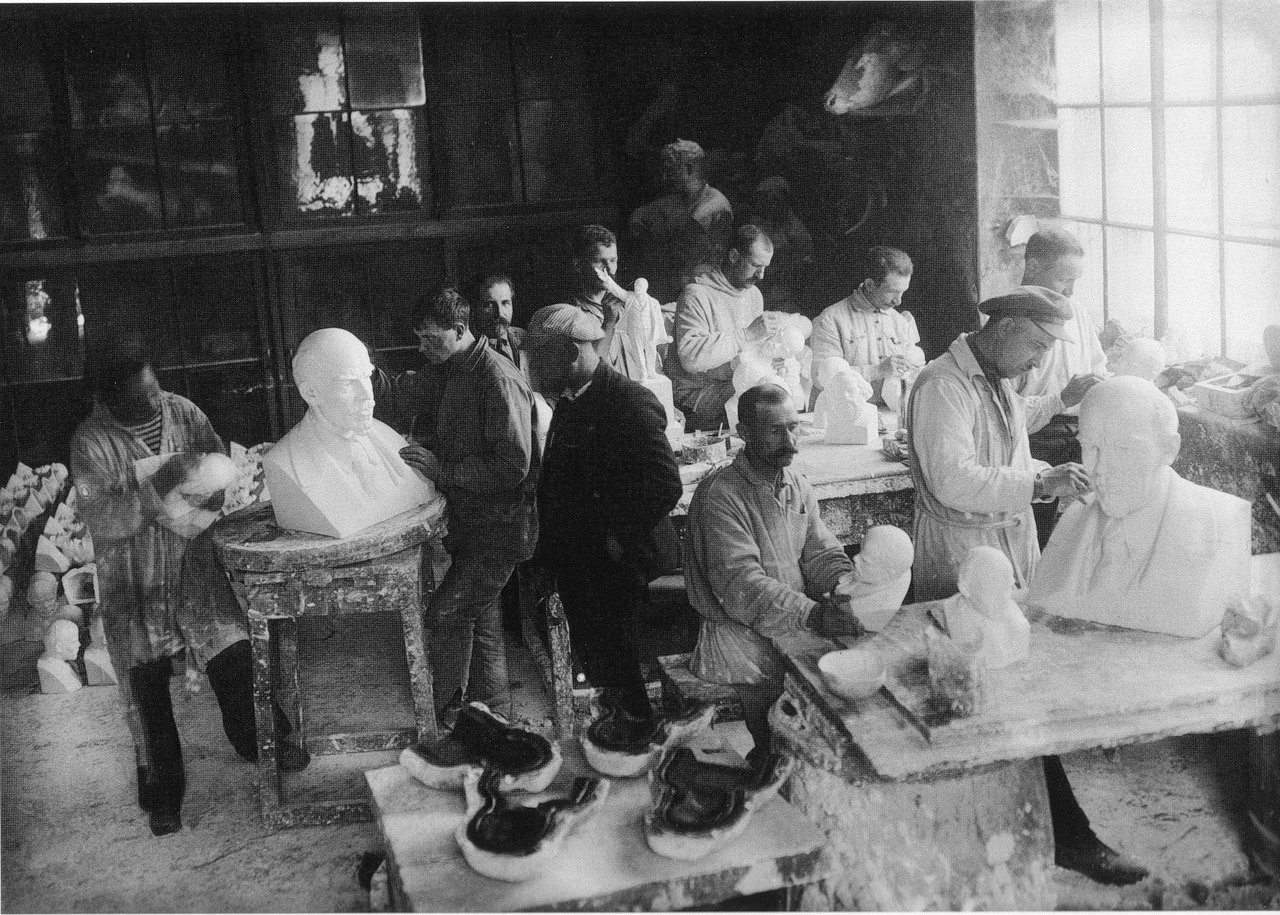

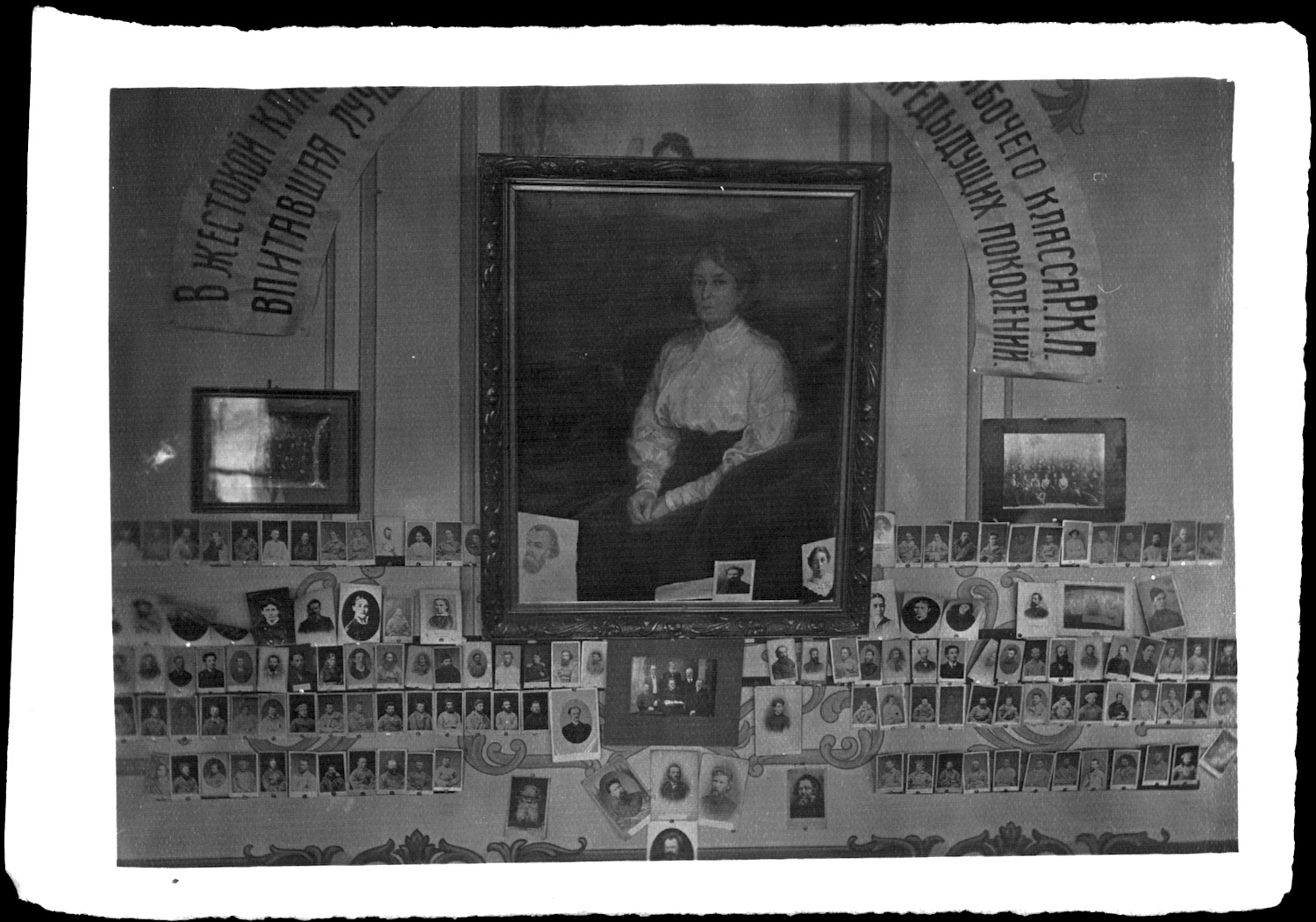

The Museum of Penal Servitude and Exile was similarly intended to materialise and affirm the narrative of the significance of penal servitude to the 1917 Revolution. The idea of opening such a museum was already being discussed among the OPK’s founders as early as 1921, and a museum commission was formed in October 1924, made up of Anna Yakimova-Dikovskaya, Yelizaveta Kovalskaya, L.A. Star, Iosif Zhukovsky-Zhuk, Revekka Gryunshtein, David Pigit, Golfarb and Baum. [31] Collection of material for the future museum was undertaken by regional associations with the support of OPK branches and other institutions, including the Museum of the Revolution. A central “Penal Servitude and Exile Museum” was founded in 1925 under the auspices of the Moscow branch of the OPK. “The museum possessed a remarkable collection of photographs and paintings, as well as textual testimony—manuscripts, investigation files, sentences, prison journals, identity cards, etc. Ultimately, by 1927, the Moscow Museum of the OPK ended up in possession of a better collection of works on the history of the revolutionary movement than the Museum of the Revolution in Moscow.” [32]

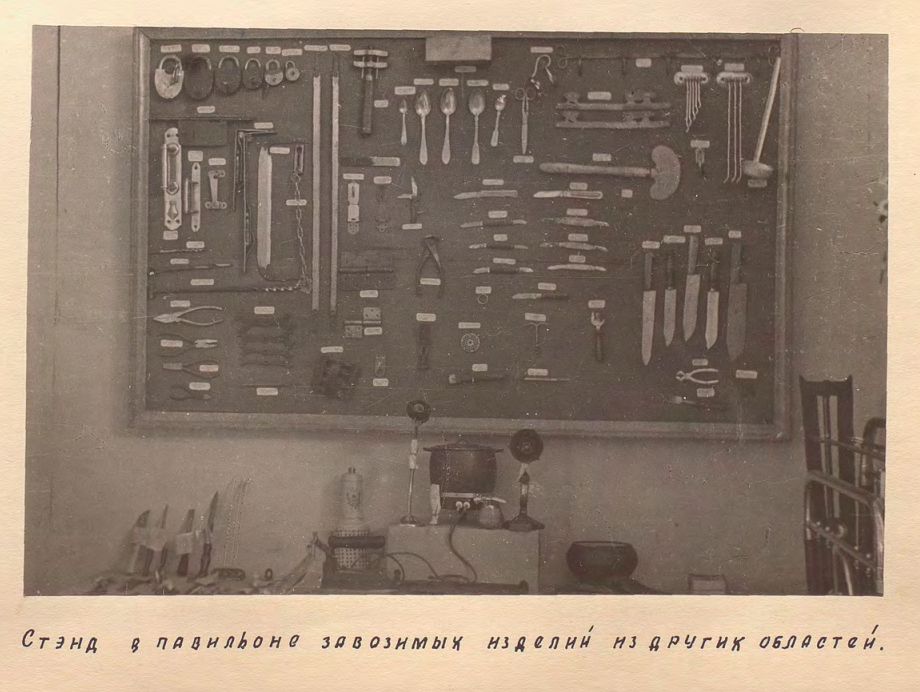

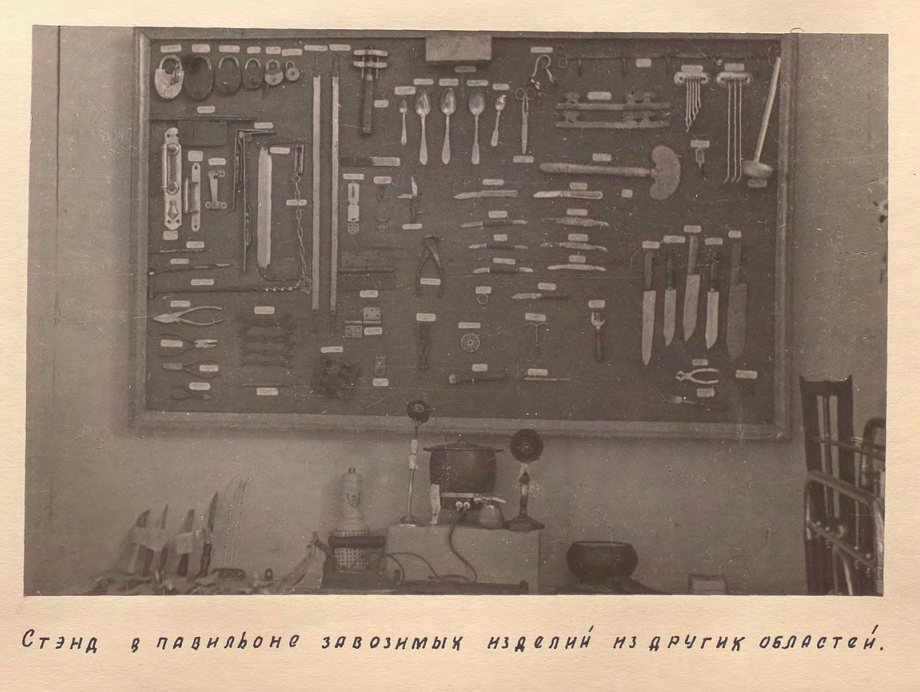

In 1927, according to a report by its director Vera Svetlova, the museum’s collection comprised up to 10,000 photographs, 61 large portraits (including 11 oil paintings), “documents, manuscripts, relics and prison artwork by political [prisoners]”. [33] They had also “processed 22 reference albums of photographs from individual sites of penal servitude and exile”, and hired a full-time photographer to reproduce old photographs, resulting in the amassing of a “carefully selected collection of 5,100 negatives”. [34] Based at the OPK Club, the museum gradually developed in line with a “monographic-topographical” logic, meaning its sections were dedicated to either a specific topic or location. Thus, in 1927, the museum had nine departments: “The Decembrists in Prison, Penal Servitude and Exile”, “Old Shlisselburg”, “New (Narodnaya Volya) Shlisselburg”, “Anniversary Exhibition in Memory of 1st March 1881”, “Prison, Penal Servitude and Exile in 1905—1917”, “Lenin’s Life in Prison and Exile”, “Exile in Yakutia”, “Alexandrovsky Central [Prison]” and “The History of the Emergence and Work of the Society of Political Prisoners”. The exhibition in one of these sections was described as follows: “11 posters, 7 large portraits, and up to 15 large glass display cases of documents and leaflets, a reconstructed ‘Shackling’ [of prisoners] scene (a group of 4 life-size figures), and 3 coats of arms with mottos.” [35]

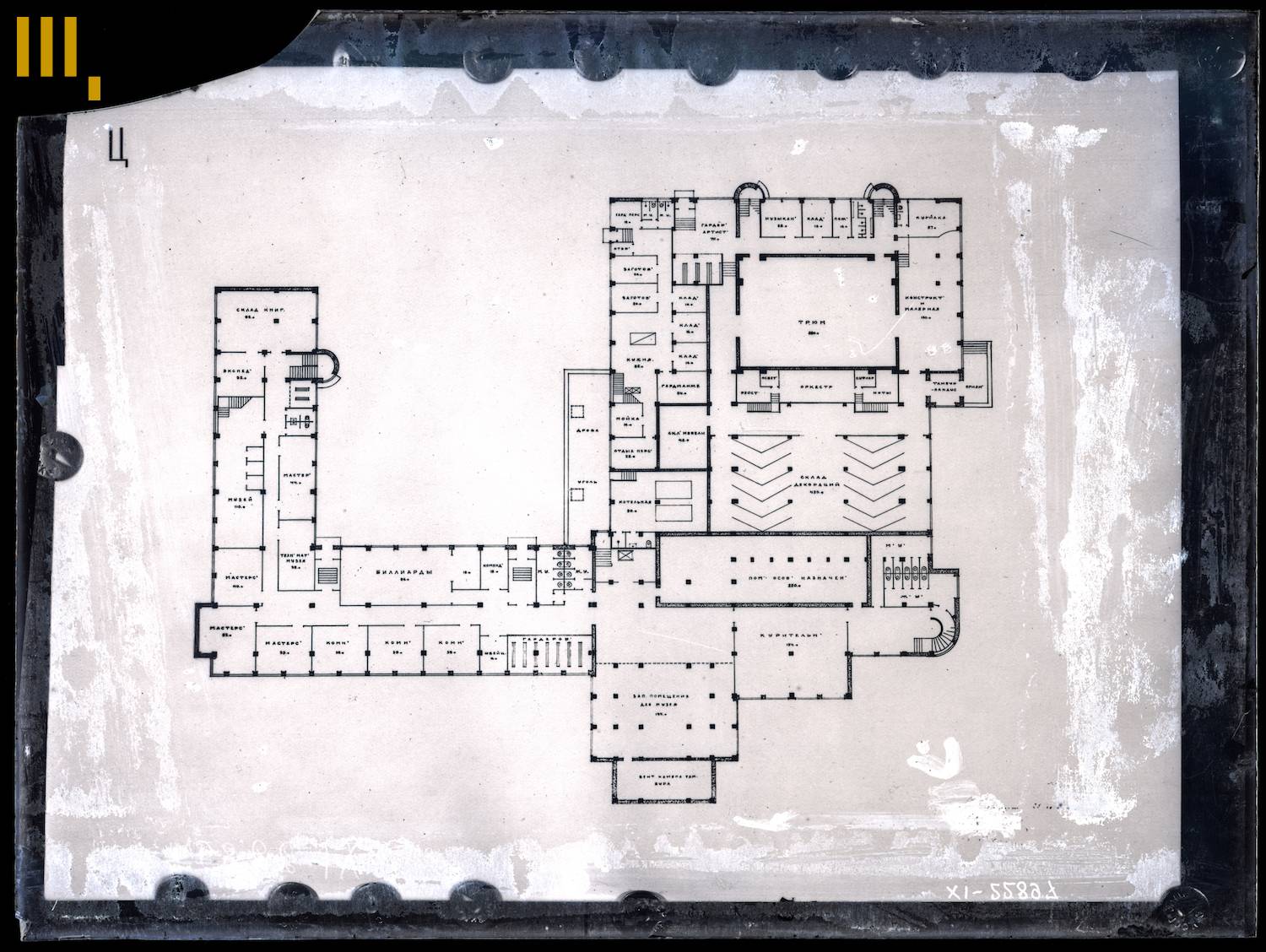

In the early 1930s, the OPK museum collection was criticised for the predominance of portraits and its museum activities were labelled unscientific. A reorganisation then followed, accompanied by the introduction of innovative methods in exhibiting and conducting museum work: the production of infographic materials, the organisation of travelling exhibitions and museum courses, and a focus on research. Centralisation and an increasing emphasis on the role of the Bolsheviks also continued: the museum’s director, former SR Vera Svetlova, was removed from her post and then sent into exile. [36] Overall, the OPK museum’s activities expanded steadily. As early as 1927, the Vesnin brothers designed the “House of Penal Servitude and Exile”—a constructivist building intended to house an archive, a museum and a club, equipped with a large auditorium. In 1930, the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR allocated the funds, and building work began. However, by 1934, only the club section had been built, while the museum section remained only on paper. Many people voiced their dissatisfaction with the architecture of the Vesnins’ constructivist building, with a 1935 wall newspaper for political prisoners describing it as a “pigeon loft on stilts”, [37] and the OPK itself was liquidated the same year. The Central Museum of Penal Servitude and Exile was renamed “Museum of the Bolsheviks in Tsarist Penal Servitude and Exile”, where the main theme of the exhibition was “Stalin’s Escape”. [38] The reconfigured museum was headed by Grigory Kramarov, one of the OPK’s leading “hawks” and the founder and former chairman of the Society for the Study of Interplanetary Travel. Thus, in the shift from the principle of non-partisanship to “Stalin’s Escape”—the heterotopia within the OPK collapsed.

Revolutionary ethics in the museum: Eternal return

The concept of revolutionary ethics is directly related to both the second mode of (self-)production of the revolutionary subject and Groys’ proposal for the reconstruction of the avant-garde cultural imagination in the museum. The development and defence of the principle of revolutionary ethics in the OPK was primarily associated with the anarchists. Thus, the prominent anarcho-syndicalist theorist Daniil Novomirsky (Yakov Kirillovsky), who had stood alongside Pyotr Maslov at the founding of the OPK, drafted a charter back in 1920 that declared the society’s main task to be “to ensure the ‘correct’ use of its members in the ‘interests of the revolution’.” [39] Novomirsky believed that the political situation boiled down to a division of actors into two broad camps: supporters of the revolution and its opponents. The guiding principle for the first camp was a special implied revolutionary ethic that had developed during the revolutionary struggle and against which everything that transpired since—including Soviet power—must now be tested. For Novomirsky, this in no way precluded the possibility of controversy and disagreement.

Novomirsky had come to the conclusion in 1920 that the Bolshevik Party had consolidated the supporters of the revolution and that being with the Bolsheviks now effectively meant adhering to this revolutionary ethic. He joined the RKP(b) and, through the pages of Pravda, called on other anarchists to do the same. By 1922, however, in his book P.L. Lavrov on the Path to Anarchism, he was accusing the Bolsheviks of building state capitalism in conjunction with an unprecedented degree of suppression of dissent: “The socialist state is the greatest property owner and the greatest exploiter on earth.” [40] This did not signify any renunciation of the revolutionary ethic on his part—on the contrary, it was precisely his loyalty to it that enabled him to criticise the Bolsheviks. Taking such an approach, any political force could move closer or further away from the revolutionary ethic, which remained the “measure of things” and an abstract, immutable principle, constantly changing its specific real-life embodiments as the historical process unfolded.

Another founding member of the OPK, the theorist of individualist anarchism Andrei Andreyev (Chernov), resigned vocally from the society in 1924, when the communist faction seized control and the charter banned membership for those with criminal records under Soviet law. For Andreyev, this was unacceptable, as it placed state institutions and their codex of laws above the “penal-revolutionary ethic”. His ideal, expressed in the concept of neo-nihilism, envisioned formal laws being replaced with revolutionary ethics, as practised by the only legitimate authority—the anarchist “ego”: “Organisation is the enemy of the individual and the revolution; organisation is the water of death poured on the living flame of rebellion.” [41] According to Andreyev, “the world is a vast penal colony” from which salvation can be won “not through rebellion, but through the fiery breath of permanent revolution”. Moreover, revolution comes not from without, but from within, for “freedom is within us”. [42] And, partly anticipating Deleuze and Guattari: “Anarchy is life, it is not an ideal nor is it a goal; I would say that there is no anarchism—there is the anarchist, the bearer of anarchy. In this case, Mikhail Bakunin is vindicated in boldly spitting in the faces of ALL counter-revolutionaries: ‘We understand revolution to mean the unbridling of what are now called evil passions and the destruction of what in the same language is called “public order”.’” [43]

At the same time, the anarcho-communists Olga Taratuta and Anastasia Stepanova (Galayeva) demonstratively left the society. In their manifesto, they spoke of the coming revolution as follows: “Like a distant but bright star, sometimes dimmed behind clouds, sometimes reappearing, the great revolution is coming towards us, and it will arrive victorious. The idea of a society of political prisoners and exiled settlers, suffocated once more in the grip of partisanship, will be resurrected in all its original glory and life.” [44]

Thus, according to the apologists of revolutionary ethics, the OPK ceased to be a bearer of these ethics after 1924. However, the main initiator of the communisation of the society, Vladimir Vilensky-Sibiryakov, would later inadvertently reconstruct revolutionary ethics within the OPK when developing his theory on the central role of penal servitude in the Revolution. By making broad generalisations based on the shared prison experience of the society’s members, Vilensky aimed to conceptualise a revolutionary mechanism that would be suitable, among other things, for export to other countries within the framework of the International Organisation for Assistance to Fighters for Revolution (MOPR, also known in English as International Red Aid). He discussed the “germ cells” of the revolution and the special role that the penal prison had played in their development.

Vilensky’s theory recreated a heterotopic optic in the discursive field, and here the work of the revolutionary machine for the production of difference becomes even more evident. The model discursive heterotopia is a “certain Chinese encyclopaedia” mentioned by Borges, which Foucault cites in the preface to his work The Order of Things. This “encyclopaedia” comprises a small classification, dividing animals into groups according to completely different characteristics, for example, “(a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, … (f) fabulous, … (j) innumerable”, [45] and so on. Point “h” covers those animals “included in the present classification”. [46] According to Foucault, this is “the limitation of our own [thinking], the stark impossibility of thinking that…” [47] What is it that constitutes this limitation? Foucault believes that the juxtaposition of all points apart from “h” indicates “a worse kind of disorder than that of the incongruous, the linking together of things that are inappropriate”. Despite the absurdity of the classification, these points share a common place, a common “table” on which they can be juxtaposed—the space of language. But point “h” destroys the “stable relation of contained to container between each of these categories and that which includes them all: if all the animals divided up here can be placed without exception in one of the divisions of this list, then aren’t all the other divisions to be found in that one division too?” [48] The “and of enumeration” is thereby destroyed, and with it, “the in where the things enumerated would be divided up”—language and its syntax. According to Foucault, “h” represents a heterotopia; it is this point that calls into question the very possibility of classification—not at the level of the content of categories, but at the meta-level of its logical possibility. Heterotopias “destroy ‘syntax’ in advance, and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things”. They produce a genuine other, a pure difference in relation to the existing order, a difference that is revolution—at once an Event, the Singularity, and the return of the most essential—the very logic of revolution.

Heterotopia should therefore be spoken of as a logical operation, an optic, a “concrete technology” and a “rhetorical machine”. [49] It is in this sense that Edward Soja speaks of “Thirdspace” as the abolition of the dualist antagonism of the first and second spaces—the physical and the imaginary. This is not a dual Other, but a perspective of “and/both, and also”, which implies a first, a second and a something else. It is a part that is greater than the whole, a collapse of conventional logic, or category “h” in the Chinese encyclopaedia. While conventional logic asserts a view of reality spied through the prism of the historical narrative, heterotopian logic implies a spatial turn that clashes head on against history. And if space is customarily perceived as either imaginary or physical, then heterotopia removes this duality. Foucault gives the example of how his parents’ double bed is a real physical space for a child at play, but also an ocean where he floats among the bedspreads, and a forest where he hides beneath its wooden frame. This place is simultaneously imaginary and physical (and something else entirely), where a different imagination is produced, overturning the usual logic of “either-or”, according to which a quilt cannot be an ocean, nor an imaginary space be physical.

Into this heterotopian logic of uniting the physical and the imaginary, we must combine Foucault’s discursive understanding of heterotopia, outlined in The Order of Things, with its physico-spatial understanding from his Of Other Spaces. Heterotopia will then arise in all its glory—as a device combining object and method; as an exception that does not fit into any taxonomy, as a queering machine that smashes through and undermines any categorisation or cartography. This is the establishment of a certain visible spatial difference to the existing order of words and things, which presupposes a rupture of the language / causality / continuity of the spatial basis to this order. This is the limit of the established; schizophrenia or a door in the wall that keeps the desert at bay; [50] “Eusthenes’ saliva”, teeming with all these unseen “creatures redolent of decay and slime” and the syllables by which they are named; [51] an impossible common place of their impossible assemblage—impossible because it abolishes the coordinates within which assemblage was perceived as possible or impossible.

The penal prison only became such a revolutionary philosophical heterotopia when it began to produce a discourse rejecting tsarism: at that moment, it became not simply a disciplinary exception but an indication of the possibility of another order of things. Groys makes the same point when he writes that a marginal position in society, such as that formed by bearing an alien cultural identity, cannot in itself provide a metaposition—being a product of the same circumstances, it is not truly “other”. [52] The journal Penal Servitude and Exile and the museum of the same name did constitute heterotopias under the Bolshevik dictatorship because they brought together disparate elements whose very existence pointed to the potential for another socialist imagination. And not so much any particular other, but one in which all of them could coexist without suppression, from members of Narodnaya Volya to the God-men, the Bundists, the Vertepniks, and neo-nihilism… Each of these individually, plus all of them together, plus something else too. The “Chinese encyclopaedia” and “Eusthenes’ saliva”, undermining the Bolshevik hegemony. The revolutionary ethic strives to constantly reassemble the established order and social code. Heterotopia is its spatialisation and its “grounding”.

We may now more fully explore the process of reconstructing the revolutionary cultural imagination in the museum. This process implements the procedure of defunctionalisation or “cutting away” from the existing order/syntax in four modes. Firstly, the museum possesses a special space with its own mode, which entails the physical exclusion of the viewer from the everyday spatial fabric—this is cutting away No. 1, the “physical” mode. By analogy with the exclusion of a political opponent from everyday space in the heterotopia of the penitentiary system, this mode can be termed “the exiling of the viewer”. According to Foucault’s classification scheme, the museum is a classic “heterotopia of time”, combining heterotopia with heterochronia and performing a cutting away or “découpage of time” (découpages du temps). Of significance here for our purposes is not so much the specificity of the museum heterotopia, but the very fact that the museum is a different space. Secondly, museum objects are decontextualised objects, torn from the logic of utility and, more often than not, stripped of their original functions. The chief method of the museum is to “exile” objects, thereby producing potential demonic relics that have come to us from other spaces and times—cutting away No. 2, the “methodical”, “museum-specific” mode, or the “exile of objects”. Thirdly, as a result of following its own method, the museum functions as a vast assemblage of heterogeneous objects belonging to completely different discourses, cultures, traditions contexts, and circumstances. Any museum is already a “Chinese encyclopaedia”, containing a whole list of point “h”s. By combining the uncombinable, the museum inadvertently points not only to the possibility of a whole panoply of alternative logics but also to the breaking up of the very foundations of conventional logic, as in Edward Soja’s “Thirdspace”. Rather than simply “either… or… or” (a mass of alternatives furled up inside demonic relics), it is also “and this… and this… and both of them together… and something else too”. Trying to somehow cope with the schizophrenic plundering of its own material, the museum frames and coordinates it within the framework of museum narratives, pointing the viewer only to strictly defined chains of code within the artefacts—but ever perched on the brink of defeat at the hands of the demonic power of its objects, which shake and smash these narratives and the museum’s logic from within. This is cutting away No. 3, the anti-museum or “maximally-linguistic” mode. Finally, the series of objects—including, for example, the avant-garde art which Groys invites us to examine—are documents of the conscious defunctionalisation of art. They belong to the revolutionary tradition in art; their code is the logic of revolutionary procedure per se. The implication is that, by hanging the code of their logic onto the hooks of their own thought patterns, the viewer can attempt to create within themselves a machine of revolutionary art, capable of carrying out the same procedure in a new historical context. Cutting away No. 4, the “art-revolutionary” mode, recapitulates the previous three and applies them to the field of art.

Prior to all this, however, a machine for the (self-)creation of the revolutionary subject must be built, consisting of a museum heterotopia, a demonic avant-garde relic, and a willing viewer. This machine creates a situation of hermetic alchemy [53]—a flow of overdiscipline that produces the revolutionary subject. The task of the willing viewer is therefore to create within the disciplinary space a situation of their own revolutionary individuation. Presence in the museum, understanding the logic of museification as the creation of potential demonic relics, and reconstructing the logic of the avant-garde through its documents—these are the three processes that stimulate the production of the revolutionary ethic in relation to art.

However, it must always be borne in mind that the machine of (self-)creation of the revolutionary subject has two modes of operation. The flow of overdiscipline generates a new law, which emerges alongside the revolutionary ethic and immediately enters into conflict with it. The penal colonies gave birth not only to a revolutionary ethic but also to a new despotic state. This duality of modes is reflected in the second thesis of Deleuze and Guattari’s schizoanalysis: in social investments, the unconscious investment of desire must be distinguished from the investment of class or interest. The latter can be markedly revolutionary in character, but is primarily defined by the task of propagating a new society, “carrying new aims, as a form of power or a formation of sovereignty that subordinates desiring-production under new conditions”, [54] and can thereby become repressive in relation to revolutionary ethics as such. Therefore, “betrayals don’t wait their turn, but are there from the very start” [55] and revolutionary groups are always ready to assume the role of repressive scriptor, guarantor, and executor of the new Law. For “what revolution is not tempted to turn against its subject-groups, stigmatized as anarchistic or irresponsible, and to liquidate them?” [56] Clearly, this is precisely what happened to revolutionary ethics in the USSR. A similar duality may be observed in how revolution in art has always been presented to us—simultaneously as a new artistic hegemon and as a revolutionary ethic, that is, the pure logic of revolution, realising its eternal return.

In conclusion, I propose we imagine a museum that does not seek to tame the cacophony of its artefacts by imposing upon them the codex of a single historical narrative. What might a museum be like that strives to act truly heterotopically? That strives to be a reformatory of the revolutionary subject, that is, to facilitate the production of both concrete revolutionary differences and revolutionary ethics? It seems that such a museum ought to contain gaps in narratives, to emphasise the incoherence of objects (inheriting the absurd logic of the “Chinese encyclopaedia”), to highlight evidence of how avant-garde defunctionalisation occurs, to explore how certain objects cancel/reassemble narratives (reconstructing applicable cases from art history), and to speculatively model similar situations, confronting coherent discourse with a heterotopia that undermines it, presented via this or that demonic relic. Accentuating the points of cancellation of existing discursive and spatial law, producing differences to it at the level of syntax, and a commitment to revolutionary ethics as such—this is what should stand at the centre of heterotopological museology.

Translation: Ben McGarr