Arseny Zhilyaev: There’s no point pretending that the topic of our discussion (“Zero Viewer” or “Other Viewer”) wasn’t inspired by Covid and quarantine. The idea of thinking about radically different approaches to exhibitions and art institutions came to me when I was reading news about the problems that London museums are experiencing during lockdown. Closed museums are actually a magnet for crowds, but for non-human crowds. As a British museum worker said: “We used to have to worry about objects being damaged by visitors, now we’re worried because they’re not here to ward off the pests.” Lockdown coupled with climate change is leaving museums unable to cope with insects, for which cultural consumption means actual consumption of exhibits for food. Webbing Clothes Moths and Carpet Beetles are usually the main danger to collections. But a relatively new species – Grey Silverfish – are now the main threat.

The lockdown situation makes us look differently at many seemingly familiar things, and human cultural heritage is no exception. You might even say that the virus has become a kind of avant-garde artist for us. Like the most successful avant-garde artists, the virus has estranged everyday life for millions and even billions of people. But it has also trespassed on cultural heritage by opening access to those who had previously been denied access. Direct parallels with events of the 20th century would probably be too provocative, but we can at least use the Covid situation to rethink the boundaries of the human, as well as the boundaries of what we consider to be part of the culture we cultivate.

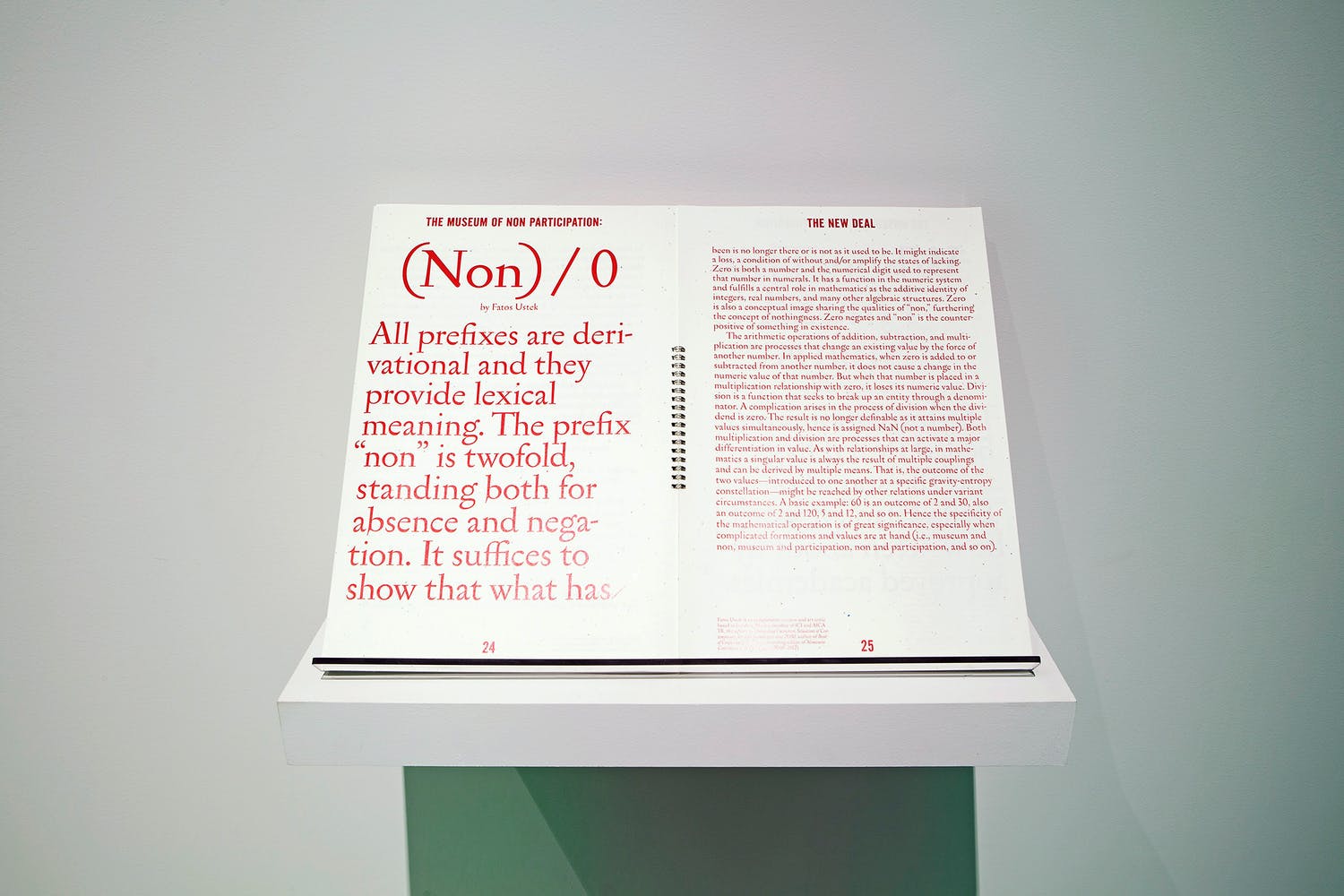

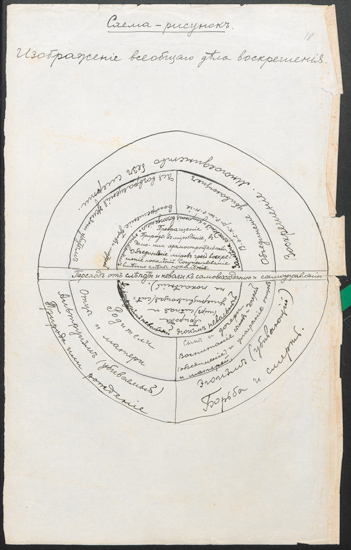

I began to reflect with my colleague at CEM, Olga Shpilko, about how viewing of museum expositions has changed due to their forced closure and about the viewers who were often excluded from museums in past centuries. We realized that this problematic leads to the idea of some kind of zero, empty viewer – a spectator who exists when it seems to us that there are no spectators at all. And it turns out that there is almost always a viewer, at least since the appearance of proto-RNA, capable of distinguishing between the presence or absence of light, heat, etc., which the mysterious Belgrade researcher Gregor Moebius tells us about. At the same time, the zero viewer can be understood as a standard – as a certain ideal or most typical spectator. And this leads us to the problems of museums after social revolutions, in particular, to the avant-garde experiments with radical museum openness in Soviet Russia in the 1920s–30s. Or postcolonial problematics, which work directly with the concept of otherness and its direct embodiment in the logic of museum activities, from collecting to display, research, etc., etc.

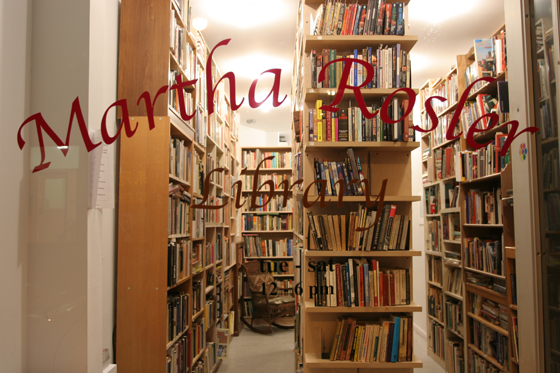

One of the first things that came to my mind in this context was the story of American minimalists like Robert Riemann, who worked as a security guard at MoMA for 7 years, where he met other technical workers of the museum, Dan Flavin and Sol LeWitt. Under lockdown, the gaze of the security guard, the gaze of the technical worker, passed through the eyepiece of the security camera, has become the basis of optics in closed expositions. This thread leads to speculations about the museum trade union movement, about criticism of the museum as an enterprise. Critics, so to speak, are an engaged viewer, drawn into the exhibition by virtue of their everyday work, which is often not recognized as equal in value to the work of a professional from art – a curator or an artist. If we go towards the camera eyepiece and media mediation, we come to virtual museums, virtual museum tours, zoom conferences of museum workers, etc. But we also come to data archives and the Internet in general as a special zone of cultural accumulation and display. I know that the Moscow Garage Museum was the most active institution in Russia (and perhaps internationally) in this respect: Garage Digital was a major event in the first quarantine months. There is a trend worth mentioning here whereby curators use social networks to create virtual projects that would be impossible in the physical world.

Coming back to the virus and insects, I was reminded of Soviet museum projects in the permafrost and even the case of a virus museum – something, about which we have been trying to obtain materials for a very long time, but so far to no avail, and which shows how the “museification” of a virus can work differently from what is happening in London museums under lockdown. The human body is also a refuge where a virus can live, although, really, the virus exists between life and death. To paraphrase the British museum worker I began from, the human body (indeed, any body) could be a “museum” for other bodies, other forms of life. Think also of projects such as “new arks”, which aim to preserve biological diversity or, in general, life after a potential disaster – protected “bunkers” with specimens of fauna, etc. Or the diametric opposite: the entombment of nuclear waste that will take thousands and tens of thousands of years to decay and that calls for the creation of a label system, designed to inspire terror in anyone who has the idea of visiting such sites. A whole science of death signs – nuclear semiotics – has arisen out of this.

Obviously, these are only some possible developments of the theme. So we have invited our colleagues to offer their thoughts about zero viewers and other viewers in their practice. Let me introduce our interlocutors: Maria Lind, a curator whose name is associated, in particular, with many years of innovative work at Stockholm Tensta konsthall and currently counsellor for culture at the Swedish Embassy in Moscow, where the issue of inclusiveness and radical openness is a central methodological tool; Valentin Dyakonov, curator at the Garage Museum, one of the curators of the 2nd Museum Triennial of Russian Art and one of the first people in Russia to start working consistently with postcolonial issues; Katerina Chuchalina, curator at VAC Foundation, co-founder of CEM and a member of the group now officially called “cultural mediators” of the Manifesta 13 Biennale, which opened at the end of summer 2020 despite Covid, raising questions of new forms of solidarity with almost no international or at least professional audience. Colleagues, who would like to be the first to share their thoughts on the topic?

Valentin Dyakonov: I got interested in postcolonial theory because it presented a dynamic that is quite different from the progressivist understanding of art, that was so much the mainstream when I started working as an art critic in the late-1990s in Moscow. The rhetoric of progress and the rhetoric of making something to fit squarely into European Western mainstream looked quite uncanny from the start, because the 1990s was not a great time to even dream of a white cube, let alone to construct it. But as money poured in and as white cubes started springing up it became even more uncanny than it was in the 1990s. And this uncanniness was absolutely inexplicable to me – I felt it but I never could understand why there is such a kind of horror in the striving for a well-worn, clean scenario. Postcolonial theory let me look at this striving for the white cube, striving for normalcy, and striving for cleanness in a new way…

AZ: Sorry, are you talking about the Russian context?

VD: Yes, and specifically the Russian art world. I’m not trying to speak on behalf of other communities and complex objects of the postcolonial inquiry. I’m using this only to understand the context of this misguided progressivism that felt so uncanny to me from the start in the 1990s and which I couldn’t understand. But from there it’s quite understandable that a lot of what’s going on in today’s museums, a lot of what’s going on in today’s art world, in Russia, is also part of the very interesting dynamic that was already underwritten by several generations of postcolonial thinkers from all over the world. Dipesh Chakrabarty makes a distinction in his “Museums in Late Democracies”, between pedagogical and performative forms of cultural knowledge. The idea is that there exists an inclusive pedagogy that is meant to help the viewer to discern between high culture and low culture. And there exists a performative democracy, something that he relates to postcolonial and decolonizing sentiment. Performative democracy means that no museum object – especially no museum object that is stored in a museum, that exists in a metropolitan context – no museum object that once belonged to a different culture can be hidden away from the representatives of this culture. So, for example, if you have the Ethnographic Museum in Belgium you should provide wide-open access to the representatives of the Congolese community, both living in Belgium and elsewhere. In the Russian context there is a very interesting development of this distinction. I once asked an artist, Mikhail Tolmachev, who was influenced by Clémentine Deliss whether the deaccessioning of the monasteries and churches in revolutionary Russia after 1917 constitutes a colonizing effort. Whether it could be described in the same terms as the destruction of certain communities by appropriating art from its original context into the context of the museum. And Mikhail posed quite an interesting setup: some museums that hold specific important collections of Russian icons have to deal with Orthodox believers who come and try to engage in religious ritual there in the museum. So the Tretyakov Gallery has a process whereby it loans very important icons by Andrei Rublev to a church for a certain day, a certain feast. The State Gallery in Perm, a big city in the Urals, also has a special section dedicated to icons where priests, clergy, and believers gather for certain Orthodox rituals. We, with our very modernist, positivist, progressivist backgrounds, fail to see these situations as examples of performative democracy. We see them in the context of a certain conservative state pressure. So what we have here is not a postcolonial situation, nor it is a decolonial situation. But we see that there are some very varied scenarios occurring in Russian museums, which are very close to what decolonial critical theory would like to see happening in museums in Europe – certain principles, performative principles that are sought after by the proponents of this decolonial discourse.

Maria Lind: This is extremely interesting. Can you just elaborate on the differences between your case study and other things that are going on? And also, what would you call what is going on in Russia?

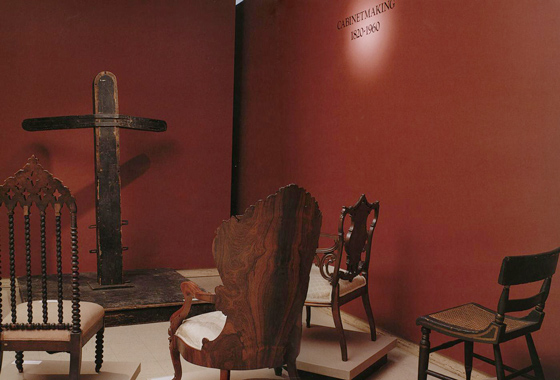

VD: That is a question that I have no answer to as yet. And that is why it’s so interesting to see the level of protection of certain works of art – and protection, I think, will be a huge topic for us here today. Because, ultimately, all the other viewers that you, Arseny, so eloquently enumerated in your introduction (most of them, at least) are viewed as threats to the specific condition of the artwork’s existence. In our case we have the communities whose artefacts were museified during the modernist push of revolutionary Russia. And then, while staying museified, they are very antagonistically, very slowly given back to those communities. But these communities, in their turn, become an argument in a culture war of the state with the liberal left, roughly speaking. So I think the most interesting thing here is addressing the question of performativity in museums for the communities that had those objects – that they have the right to engage with these objects – and this enlightenment impulse that makes us think of religion (and especially a religion that was so married to the state as Orthodox Christianity) as an enemy of those models of democracy that we strive to implement. And this is, I think, a paradox that has to have an explanation, has to have a certain name. But it’s very much connected to all those interesting developments in museology that Arseny knows so well. And the class and social developments in museology during the 20th century in revolutionary and avant-garde Russia are also part and parcel of this problem that we face now. Because while we usually think of avant-garde museology as something that is in many ways didactic and pedagogical, it’s also pedagogical in terms of a certain standard of performativity, a certain standard of behaviour that the former “other” viewer is supposed to have in the space of the museum. There was a very thorough exhibition in the Tretyakov Gallery on the Museum of Painting Culture, which was conceived as a kind of pedagogical museum for the new hegemon – the worker, – showing the development of European painting in all of its avant-gardes. But there was a beautiful document in this exhibition, a type-written document that laid out the rules of presence of your body, and first of all of your feet, because we have to remember that snow and dirt were the main features of a Soviet road in the 1920s. And so you had to watch your feet, you had to keep them clean in order to enter this pedagogical space. So this is, in a way, the invention of a new audience through transforming the level of threat which this audience posed to the integrity of the artwork and to the integrity of this enlightenment model of pedagogy.

ML: Which led to the use of tapochki in museums, which was a uniquely Soviet experience.

VD: It highlights something about the road that leads to the museum. It’s usually cleaner, it’s more…

ML: As well as noting that the behaviour of visitors unused to entering a palace-like setting to experience painting and sculpture is something that has concerned museum managers since the days of the first ever public museum, the Louvre, opened in 1792, I would like to ask something. According to your account, we must then be able then to imagine that a certain group is coming to some museums to venerate particular icons underpinned by a strong conservatism, which happens also to be supported here by the official powers. But we can also imagine groups from, let’s say, Congo or anywhere else in the world with objects in museums elsewhere also being reactionary, conservative, etc. It is not automatically linked to some kind of politically critical approach.

VD: Yes, of course, I’m not taking sides here. It just fascinates me, like a Mandelbrot fractal, the amount of different directions this notion of safety of an object could go in. So, we preserve something, and we preserve it, technically, better than the original location.

ML: You seem to underline that there is a difference between the Belgian Congolese example and the Russian Orthodox example in terms of political grounding and intention. That would be a major difference. You are right about some cases, but surely not for every case.

AZ: Could I add something here because I know some texts from the 1920s and 1930s related to this war against religion and the possible museification of religious objects. For instance, there was an important material by Pavel Florensky, who was a priest and a true believer, but who also worked at Vkhutemas. He was involved in the work of the Commission on Preservation of Art and History Monuments of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius (the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius – one of the most important monasteries of Russian Orthodoxy). Florensky wrote a strongly critical text against such museification. His main argument was that a church provides a very unique aesthetic experience based on a synthesis of the arts. It is kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. Religious ritual is not only icons, but a performative action, choreography, it has particular smells (a very unusual medium for high art), it has a special system of ethical, mystical relations with believers, etc. (in contemporary terms we could use word “happening” to describe this aspect). This is a very complex phenomenon and it’s not possible to repeat such complicity in the same way in a white cube or in any secular space, even if we are talking only about artistic features.

But the museologists were ready for this argument. Their answer was to elaborate an even more artistically effective entity, let’s say to make a bigger, more total installation than the church itself. And, within this frame, to provide ground for unification of believers and people who do not believe, and at the same time to provide critical distance. Lenin was not against admitting people of religion into the Party. There was the relatively infamous case of the Godbuilders group, organized by Alexander Bogdanov, Anatoly Lunacharsky and Maxim Gorky. They used religion as a metaphor for the real thing, where the proletariat became God, etc. There were a lot of problems after the revolution, and religion wasn’t the main one. However, at least in theory, the Bolsheviks wanted to preserve the cultural heritage of religion through critical museification. So, in a church-museum one might compare beautiful icons with the history of their production, sponsored by people involved in corruption or political crimes, or compare beautiful choreography with techniques of torture employed by Christians. It was a very aggressive approach to enlightenment, but very close to what we had in Lenin’s rhetoric and comparable with dada style or the ambitions of avant-garde artists.

And one more thing that I’d like to mention here, speaking about different communities in the 1920s; there was a community, called in Russian “Voinstvenniy bezbozhnik”, which means “the militant atheist” – a militant, anti-religious activist community that was very influential. It had several million members according to some sources. It was very big group of people and, on average, they were much more radical than museum workers. So by preserving icons within a museum museologists prevented their destruction, or their sale on the black market. However, they could also be sold by the state…

VD: Something I would add: this opens up two important questions about the history of veneration of objects. The first important question is a completely forgotten history of grassroots atheism that existed as a sect in the Russian Empire. It was regarded as a sect. There were sects that were militantly anti-God, anti-panpsychism, anti-everything. So there was this small group of people, maybe tens of thousands, who were practicing a sceptical atheism. And these weren’t professors of universities in Saint Petersburg – they were merchants, workers, and peasants, people who did not construct this worldview intellectually, through writing, but who adhered to it. This is one thing. And the second thing is, obviously, that this rescuing of religious objects in the 1920s and 1930s and display of religious objects later, in the 1950s and 1960s, was in many ways an act that was almost religious on the part of the museum worker, particularly for a type of slightly dissident museum worker in the Soviet Union. If you produced a display of icons, you most certainly tried to figure out how to talk about theology and belief systems. And the viewer was often, perhaps not Orthodox, for some political reason, not openly Orthodox at least, but was a pious person in many ways.

Katerina Chuchalina: Hi, I’m sorry, I’m late for this great gathering of people. I’m trying to imagine how you got to the point when I joined the conversation.

VD: Well, Maria asked me to start because I work in the only institution that is currently open. And I just went on a topic that might make our dialogue unpublishable in Russian, the topic of icons and the performative aspect of communities that are taking back religious displays in Russian museums.

KC: Okay. Makes sense.

AZ: So the other viewer as a true believer.

VD: Yes, the other viewer is not the disembodied eye of modernism, but a part of a community that venerates certain objects regardless of their level of safety or use.

ML: I’m thinking about the notion of the museum and the notion of the art institution, which we have already used several times. Let’s make an obvious distinction between museums with collections that display objects that are considered valuable in different ways, and non-collecting art institutions. It can also be useful to distinguish between public and private institutions, and between profit and non-profit. The conditions of each of those differ, sometimes radically, depending on the context and the economic, social and political conditions, and the borders between them are porous and fluctuating. This in turn affects how visitors behave in the space, both in terms of expectations and in terms of real, concrete behaviour.

The notion of the viewer is something I don’t use that often, but rather “visitor”, or “experiencer” to imply a broader experience than just vision. For example, at Tensta konsthall we would talk in terms of “visitors”, “partners” and “collaborators”, in the plural. Not rarely these are mixed. The idea of the disembodied viewer that relies so heavily on vision is quite limiting, similarly to what you described before about the comparison of the Gesamtkunstwerk/total installation/happening with the Orthodox church experience.

Many institutions had to close during the pandemic, both museums in the state-run sector and smaller, less formal ones, leading to a different kind of relationship with the objects and artworks in question. This different kind of relationship is potentially interesting, for example, in relation to the people working there. What does it mean to still be working and taking care of art in a museum that is closed for a longer period of time? What kind of relationship can you create, what kind of alliance can you forge, as an employee, to the art works? We have films like A Night at the Museum, which touch on this fantasy. I lived at the Kunstverein München for a couple of months at the end of my tenure there, when I had to give up my apartment. It was fantastic to be with the art works at off hours, barefoot and wearing pyjamas for example! And I once stayed overnight at Tensta konsthall with my son, which was exciting for both of us.

Maybe this is the beginning of a slightly different kind of relationship with art works. When institutions reopened, you had to book slots to visit an exhibition, making for a more solitary experience than usual, and attending openings with smaller groups – first come first serve – sometimes groups of six to ten people. I hear colleagues speak about a clearly different engagement between people and conversations arising from these smaller groups that they had not been experiencing for quite a while. This seems to be something to do with qualitative exchange that has come in the wake of the limits on access due to the pandemic. But then I was thinking about another thing, in relation to your text, Arseny, and what was said at the very beginning – what you mentioned, Valentin, about icons: that certain icons are lent out for a day, for a certain ritual or procession.

This ties up with cabinets of curiosities and other early examples of how paintings once went public. In Italy, for instance, during certain saints’ days particular paintings would be taken from churches and paraded through the city, and now we’re speaking of the 16th, 17th, and even the early 18th centuries. For me it is interesting to think how paintings get some fresh air by being part of a social context, making new and different acquaintances.

Something similar resonated with me when I saw documentation of Lina Bo Bardi’s presentation of the collection at the MASP museum in Sao Paolo for the first time – the absolutely incredible building that she designed. She was also responsible for how the collection was displayed – the famous concrete cubes, which act as feet in which a sheet of glass is placed, and then the paintings are placed on the glass. The scale of these screens is very human. This is reinforced by the fact that many of the paintings on the photographs I’ve seen are portraits. You have the head at about the height of the human head in that space, the paintings are like individuals spread out in the room. In this way, the artworks kind of “come alive”.

How art goes public is obviously at the core of this, which brings us back to the question of the white cube. But the white cube is only one way amongst so many. It is fascinating that the other ways have been so restrained for such a long time.

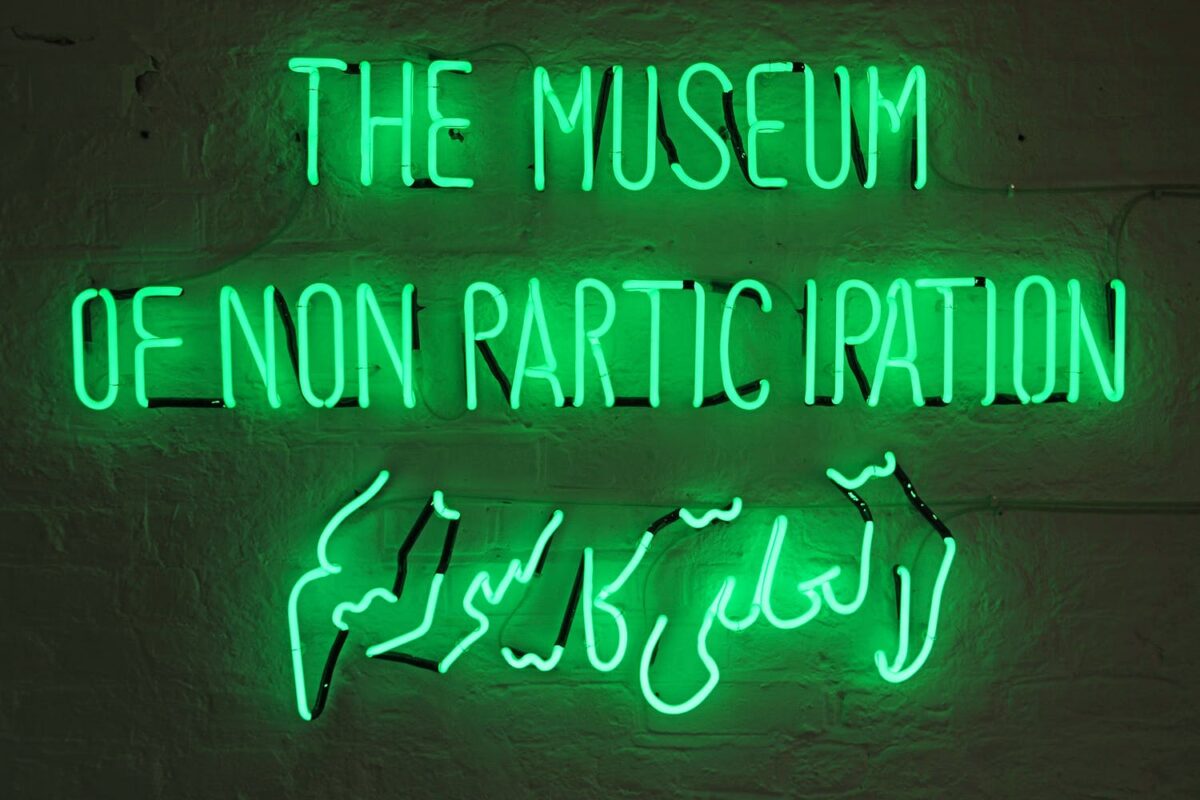

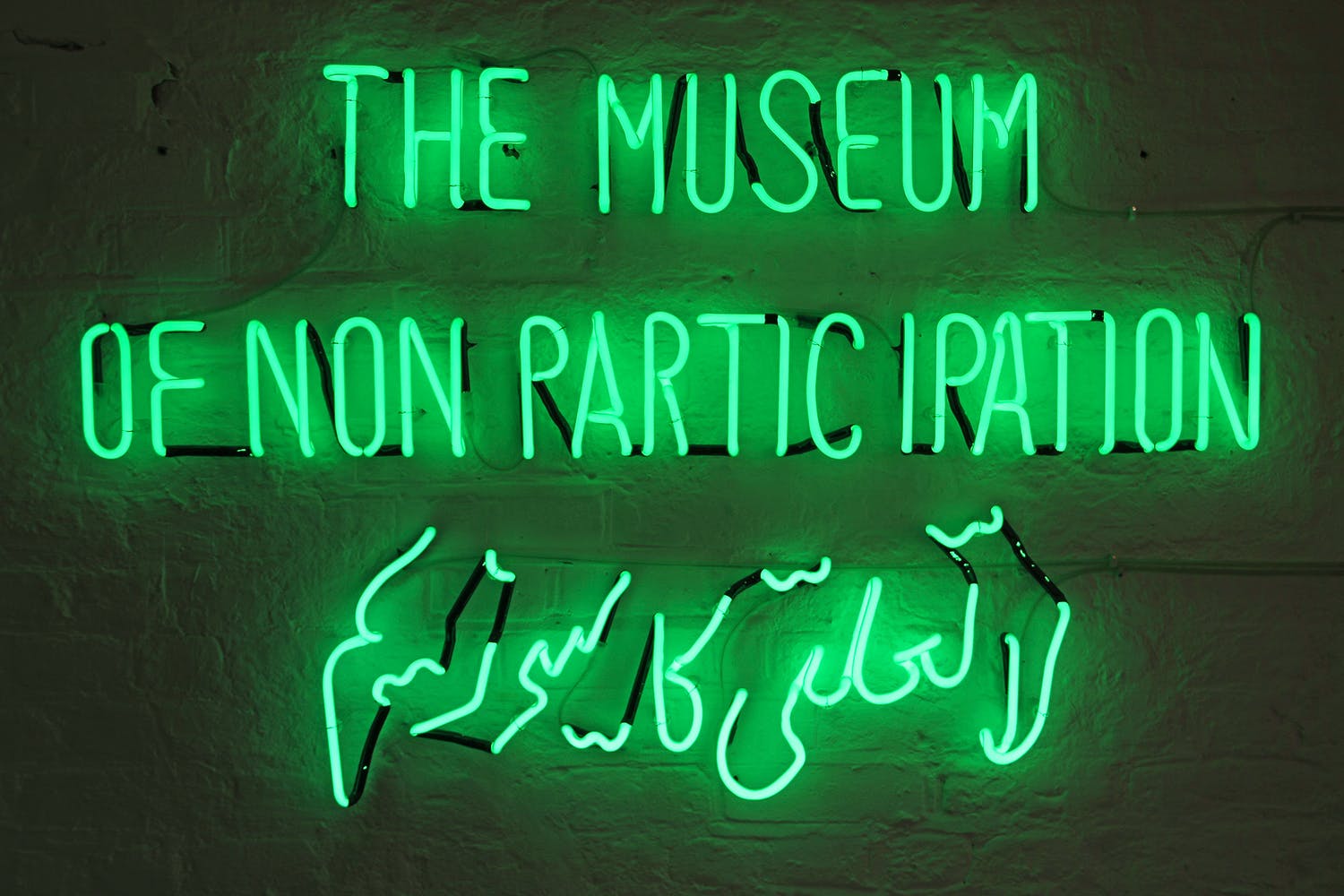

KC: Yeah, sure, the distinction between art institutions (which probably perceive their visitors more as collaborators and partners) and museums (which rely on the visibility of their objects) makes sense totally for me. Because I’ve also been thinking that what might happen is that they might swap these particular characteristics, which are part of their identity. Art institutions might swap this collaborative or inviting perception of their audience with museums, which in most cases lack it. And this is kind of the best scenario. But the most realistic scenario for me, at least what I’m seeing, is that the worst things in every institution are aggravated, it’s getting worse and more re-built. So it’s like, when you’re not prepared to look at your objects as part of a conversation, rather than an object in a storage, the pandemic will not make you more prepared to do it. It’s more likely that this characteristic will be even more apparent in what’s happening in your institution. But a distinction should be made. Definitely. It’s a core conversation for me, a kind of an illustration of today and today’s events. Because it’s literally three minutes till the moment when Manifesta is going to end and finish, because it was untimely, due to the second announcement of lockdown in France or Germany. And, I mean, we’ve been going through this period with the invisible, uncertain, very big figure of a viewer or visitor. And it’s also been said between us all the time that it’s going to be a ghost biennial. But a ghost biennial, a ghost phenomenon is something that lacks enough witnesses. Because a ghost is something that someone saw and someone not. And since Manifesta has been opening gradually, by slots, by different venues, one by one, some people saw part of it, some people liked it, some people didn’t see it. So there’s a lack of opinions, of the critical amount of opinion which is needed to prove that something exists. It lacks the figure of the witness, who verifies the existence of an art project and art institution (Manifesta is a project and an institution at the same time). And it’s interesting that this witnessing becomes a proof of the existence or non-existence of something. It’s happening all over the world. And it’s also happening with journalists: some people wrote to me from Oslo that a journalist there wrote a review of Manifesta and a colleague asked how it was possible, since he had never been to the venue. So there’s a kind of falsification. You rely on what you get indirectly. He didn’t mention that he hadn’t seen it, that he wrote the review using online information. He just writes as if has been there. And that’s also interesting. And, yes, a lot of things are ending immediately, because, of course, we saw this coming. I mean, everybody could see this coming, Emmanuel Macron was about to announce the second lockdown. And immediately the communication team approaches you with these 3D virtual tours mediated by the team of mediators. So I immediately jump from my physical experience to understanding what kind of virtuality can be produced at this point from what is still kind of alive. It’s not something which has been conceived initially as virtual, and the question is whether or not it can be transformed into virtual tours, into 3D tours. And apart from the fact that it looks kind of repulsive, I mean, as an instrument, it definitely changes the temporality, and your rhythm, and the perception, and everything. And it’s a question that is even more acute now, because Manifesta has only been open for three weeks instead of two months. So it’s a moment to face the question whether these 3D tours make sense. Or would it make any sense to suggest to people to enter the project, while the physical environment is closed. So, yes, apart from all the sentimental things here, these are things we practice now, I think. It’s not a theoretical conversation, not at all. What we are all exercising with is: what is a gaze now, where does it come from, how can it be transformed? That’s an interesting conversation, I think.

ML: More than anything we are familiar with the phenomenon of digital showrooms, exhibitions online, all of that, which is basically replicating something in physical space digitally. But I felt an urge, when the first wave came in the spring, to actually go out and look at art in the physical public sphere, from statues and monuments to art at the subway station and billboards by artists – whatever the city I happened to be in had on offer. Most cities in the Northern Hemisphere have something like this on offer. This is a good moment to look at these things anew. What does it mean to have access to art like this? Maybe we are spoilt, not caring too much about this, and certainly not all public art is great, but it’s an interesting category and there are definitely good examples to be found.

KC: Yes.

ML: We can think of it as “the witness game”. If one pushes that a little it’s the type of the tourist-visitor who goes to blockbuster shows. They went there to have witnessed the Picasso retrospective or Dali retrospective or whatever it is. Not to mention Mona Lisa. The question is, what kind of encounter is that if we are discussing the qualitative encounter with an artwork.

KC: Yes, definitely. I mean, for a biennial like Manifesta, which positioned itself as very site-specific, city-specific, it was a challenge. Because they were always saying we are for both local and international audiences. But life proves otherwise – you have to learn how to really get engaged with a local audience without an international one. And that was like the change of the whole mechanism. What is also interesting is the representation of the figure of the viewer, because we all know that there is this documentation of the opening, and the vernissage, and everything. And the viewers are supposed to be there in these photographs – engaged, enthusiastic, belonging to this. And Manifesta or any institution is desperately looking for this. I wasn’t at the opening of the Moscow Triennial, I don’t know how it was in Moscow. But in Marseille there was an absence of these faces, by protocol – any protocol said that people should be in masks. And it’s interesting how you’re going to compose and basically make up these photographs of the audience being present and in the same way enthusiastic. Because there is this inertia of representing a visitor, a crowd as happy and enthusiastic, and it’s not the same, it’s different. It’s different, for one thing, because there isn’t the same crowd, the international crowd – the international opening of the Biennial. The second thing – there is social distancing, people are in masks, people are anxious about being in the public space, so the faces are different. They look differently, people position themselves or behave differently. I don’t know how it was in Moscow. Valya?

VD: I’ll return to your question about how it was posing with masks for the press wall. It was quite a fun experience. At last, everybody noticed gloves. Previously nobody noticed how the art world looked, nobody knew the brands – the extremely expensive jackets and pants. But now with facial expression firmly under the mask, the brands can start to speak more voluminously… I’m joking, of course. But we have quite an experience in providing these 3D tours of our exhibitions. The first one was the 3D tour, this kind of 3D experience for the Atelier E.B: Passer-by show, which was closed during the pandemic because it was supposed to be up until June. We extended it to the end until August. In many ways, the scarcity of visitors makes the conversations in the exhibition space much louder, and probably more interesting. And at the same time, when you provide this super high-tech way of looking at an exhibition – as in the 3D presentation – you provide the existing audience of the show with a tool to make themselves acquainted with the content of the show. You draw a bit of a new audience too, because, if it’s done right, it’s a technical gimmick that shows off the effects of presence in this space. But once this new virtual visitor understands how it’s done – she or he – they just move on. And they’re not interested in the fact that it expands the audience. It’s something that informs the audience that the institution already had, the audience that already had the motivation to come.

ML: It is more about not losing the friends that you already have. You have to keep the plates spinning on top of the sticks, like at a fun fair. It can certainly be exhausting, even if it happens digitally.

VD: Absolutely.

ML: This is definitely fuelled by anxiety.

VD: Absolutely, absolutely. That was our motivation for all of the virtual endeavours we were pursuing in the spring of 2020. We didn’t want to lose the core audience. We didn’t want to lose the general audience, even. We wanted to keep it as it was before March 14, when we closed. And so we had to invent new ways of keeping in their feeds. The feed is what your cultural and even personal make-up looks like now. The feed is how it’s formalized. So we kind of doubled down on the Facebook feed, the Instagram feed. And that was – yeah, absolutely right – that was kind of a tool for preserving the existing audience.

But then again, there’s an interesting thing that I remember now. I’ve been to the museum when it was closed – we had meetings there, we had discussions there outside of the exhibition context – and I’ve noticed something that… I don’t know, maybe it will go, it is slowly going away now, but there was a very interesting development in relation to the migrant community here. And migrant labour in Moscow as a whole. I have a friend, Chinghiz Aidarov, who’s an artist from Kyrgyzstan. He works as a delivery man for a company that delivers food. And he told us that in the city that was empty, he became a romantic symbol of freedom for the passers-by. They were cheering him on, they were looking at him as a citizen of the city, not as a Gastarbeiter, so to speak. And I felt this effect in our staff too. We had the privilege of not laying off any essential workers during the quarantine. And I felt that they finally have this amazing privilege of, you know, having the museum to themselves. Mostly only curators have this privilege, because I can be in my exhibition or any exhibition in Garage at any time I like. I can take off after a round table and just, you know, wait for the night to fall and walk around the Triennial. And they had this feeling of owning the space for this period of time.

ML: It’s important to keep being reminded of the encounter with art and how that happens differently with different groups, and obviously the invigilators, the guards, the hostesses are the main people here. As so often, artists were there long before us! Think, for instance, of the work of Fred Wilson with African-American guards at the Whitney Museum, but also somebody like Mierle Laderman Ukeles who took on a job as cleaner, immediately entering a very different relationship to the institution. And, Arseny, I like how you bring up the virus, and the bugs, and the silverfish, etc. Again, think of artists who have done things like this. I am thinking of art works like Francis Alÿs’ surveillance video with a fox at a closed art museum, and Bojan Sarcevic’s video with dogs in a closed church.

AZ: I want to add something about this virtulality mode. In my opinion, forced virtualization of exhibitions today is mainly fuelled by huge commercial enterprises, like art fairs that organize viewing rooms, etc. Not all museums were prepared, not all museums had good, you know, virtual programs and money for organizing 3D scanning before Covid appeared, etc. But art fairs did have this. And when you talk about this new way of experiencing exhibitions under lockdown, we’re losing locality – along with materiality we’re losing locality. We have only… I wouldn’t say an international audience, but we have an audience without location. And this isn’t necessarily connected with the market-driven impulse. But it’s quite different for, as Valentina said, the core audience. So we are going to a kind of new universalization, which could possibly have good sides. But, on the other hand, this could exclude a lot of things.

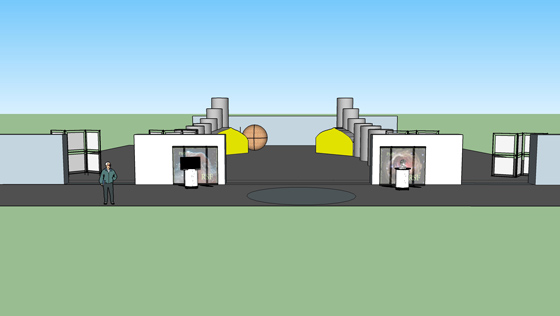

KC: I’m more kind of interested in the figure of an angry viewer. Like a viewer in a rage. Also because I’ve seen a lot of different situations, not only physically in Marseille, but virtually heard about different situations which evolved from the pandemic, which were accelerated, were caused and accelerated through the pandemic. And there are the two instances which happened in Marseille. One is what happened with the part of Arseny’s work that was vandalized there due to islamophobia, basically. And it’s not the only work for Manifesta that was vandalized – the wires were cut in a sound installation in the museum, by a museum worker, by an invigilator. That was interesting too. And I also witnessed the acts of political disobedience by museum invigilators to the new Mayor of Marseille – they basically just closed the doors to her when she came to see Manifesta, just closed the doors because they didn’t vote for her and didn’t want her to come. And another thing is that there was one venue in Manifesta which was affected, because the artist who was supposed to take over the whole venue couldn’t travel. That was Marc Camille Chaimowicz. So the venue was almost abandoned, and we didn’t make extra efforts to replace or to fill these gaps and to pretend that everything was going all right. We didn’t make efforts to change that a lot. We’ve added some works, but it basically stayed very empty with the nails on the walls – sad, a bit lonely, unlocked. And we had a huge book of complaints from viewers in rage, saying that they can’t bear the emptiness and that they had been queuing to see emptiness (because people are queuing now because of the limitations and the protocol). They had been waiting, because there was a first lockdown and everything was closed, and they were anticipating coming there, and what they saw was emptiness. Or not complete emptiness – there were just voids and lacunas. And something like emptiness was present as much as the artworks were present. So we had the whole visitors’ book of viewers in rage. I mean, I do realize of course that people, who were not in rage, didn’t leave those remarks or commentaries in the book. Yes, but it’s a very interesting document. I mean, this is anxiety about the museum being full, being packed, being ready, ready for the visitor. This kind of fear interests me. And it’s interesting in a good way – the figure of the angry viewer and how you deal with this and how it has been changed by the pandemic.

ML: Are you interested in the angry viewer regardless of motivation?

KC: No, motivation is what is most interesting. I mean, there are different motivations, I don’t limit them to one or two, I mean, there might be different motivations and different ways of expressing them. How are you as a viewer allowed to express anger? What is this borderline between vandalism and expressing your attitude? How do you define this edge?

ML: Arseny, let me answer your question about Tensta konsthall. The most important thing was to have a sophisticated program of contemporary art. And then – adjacent to it, close to it, in close proximity to it – activities that most of the time grew out of art projects, in one way or another. This meant that art would sit next to language classes within the framework of Ahmet Ögut’s art project, The Silent University, but also meetings of the local city administration, the annual assembly of a local association, or an activist group protesting against a nearby highway, etc. There would always be space for smaller gatherings within the walls of the institution, and it would be free of charge. This was extremely rewarding.

The core of what I do is dealing with “how art goes public” and how individuals and groups can have a qualitative encounter with art. This goes for professionals as well as for others. It’s not outreach in the sense that art is thrown in people’s faces. Art was on display and in other ways available to be experienced and brief introductions were available for those who were interested. But you could also just come to whatever you needed to do at the arts centre and not bother about the art. I find this proximity principle productive, to just get used to hanging around art, in a de-dramatized way, is often the first step towards what I called a qualitative encounter with art. Everything was apparently halted at Tensta konsthall during the pandemic, and then it was slowly picking up before it closed a second time. During the brief reopening the brilliant woman in charge of the language cafe which is part of The Silent University, Fahyma Alnablsi, who is also the receptionist at the konsthall, had initiated walks. Instead of meeting around a table indoors to have language classes, they actually go out and walk together. I’m sure they learned a bit of Swedish while doing that too, possibly even more.

VD: It’s interesting how the question of the angry viewer is connected to this zero viewer that Arseny introduced in his intro text. If you juxtapose the angry viewer with the zero viewer, you would almost see that the zero viewer is this cold blooded viewer, a viewer who is dispassionately going through the institution just because they have to be there – it’s a function of the institution, maybe something that we can all project our expectations onto. It’s very instructive to put all our projections into this disembodied figure. I don’t know the exact motivation of the people who vandalized Arseny’s artwork in Marseille. A similar scandal unfolded recently, thankfully without vandalization, in connection with the Tretyakov Gallery, where a label to a work by a Chechen artist Alexey Kallima was blown out of proportion by conservative websites and telegram channels. They said that the Tretyakov Gallery curators who wrote this label were basically Chechen apologists and were promoting terrorism – just by writing what they saw in the painting. The work is basically a variation of a European battle painting where the protagonists are Chechens. So they’re kind of this macho stereotype that he was playing with. These angry viewers were against what they deemed to be political betrayal by a national institution. I think that we either have to be ready for the angry viewer, for the viewer who feels betrayed by what is shown. And there is a plethora of motivations and worldviews to be betrayed in an exhibition space. Or we could just maybe try to kind of “zero” our displays, to achieve chilled-out displays, to get them closer to this zero visitor’s state. We could work around certain political topics or make them more inclusive.

ML: Would it be useful to distinguish among the angry viewers? The discussion around certain artworks in the US over the last couple of years, connected with the Black Lives Matter movement, also involves angry viewers. I was more of an annoyed viewer when I was a young critic, fed up with a certain kind of expressive modernism in various ways connected to masculinity that totally dominated the scene in Scandinavia. Today I am an annoyed viewer in relation to superficial, often commercially viable art, wherever it appears. So there are different motivations, and different expressions of this anger and annoyance. A significant aspect of what you are bringing up with the angry viewer is that we have somehow become accustomed to an affirmative paradigm in art. In general there is an agreement about what we’re showing – we might not love it or we have reservations, – but it’s an essential agreement that this is reasonable and relevant art. However, what we see more and more, also in the rest of society, is that that agreement is broken.

KC: Yes, but I do consider the anger to be an essential part of the visitor’s experience. What I’m saying is that it’s very important to see it as part of the rule. If you’re a visitor or on the curatorial team, you should consider that. I mean, this emotion is very palpable, it’s very physical, sometimes. That’s why I was also thinking a lot about virtual tours. Because if you go 3D, where is your angry viewer? Where is he? He just leaves. He does not exist. These emotions are cut out of the picture.

ML: What about chatrooms and comments? Female politicians and female public figures for instance often experience this in their feeds, directly and disgustingly.

KC: Yes.

VD: Yes, we have Facebook, which will alert us to any anger that is brewing in regards to the 3D display. But I don’t know if it’s really that widespread. Our strategy at the Garage Museum was always to have this safe strategy that sells a certain lifestyle, a certain fashionable presence above a substantial conversation about what the artwork could possibly dig up in the viewer. So that is the second consideration after the first consideration, which is to present it in ways that are not militant. It is something that relates more to the high-end experience of visiting a museum of contemporary art, where you’re supposed to be a little disoriented at times. Because that’s what the artworks are sold to you as being emotionally, that’s what their emotional effect should be. That’s kind of a safe thing to wrap any content in. And that usually works for Garage. But it doesn’t work in big projects and big site-specific projects like Manifesta. Manifesta is always surrounded by different types of angry viewer. And these types are also site-specific to the cities where Manifesta takes place. So you had one type of angry viewer in Saint Petersburg, you had a very different type of angry viewer in Zurich. You, Katya, have a new type of angry viewer who is culturally related to the situation in Marseille. Manifesta basically fishes for angry audience. And it’s like a film, a film that you put in a chemical compound. You see the portrait of a certain angry viewer in a certain European city slowly emerging. And it’s a very interesting work in progress. I don’t know about all Manifestas of the past, but in my experience they all had those political tensions. Saint Petersburg is a great example. It’s obviously a great example because it was an amalgam of angry viewers who were betrayed by the Hermitage showing contemporary art. It was also the angry viewer who was betrayed by Manifesta for showing contemporary art in a country that prohibits LGBTQ propaganda. The list goes on, and on, and on. But in Zurich there were also sections of the population that were betrayed by Manifesta. And so, obviously, when you take on the job of curating Manifesta you have to expect the angry viewer to show up at some point. And as Manifesta is so connected to questions of urbanism, questions of gentrification, questions of the positioning of certain cities – that creates a whole new class of angry viewers who might not even go to the exhibition, who might not be physically there, but who will be angered by Manifesta taking place. This is an interesting project in and of itself, which makes the angry viewer visible.

AZ: What is new today is that we have other types of otherness, different from what we usually consider as other. And this new otherness is questioning contemporary art in general. I listened recently an interesting presentation about Oscar Hansen’s heritage, made by Sebastian Cichocki, Tomek Fudala and Łukasz Ronduda from the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Oscar Hansen was a quite well-known architect and theoretician from Poland who worked in the 1960s. He elaborated the idea of open form applicable not only to architectural work, but also to museum activity as a public institution. He also proposed a special version of happening or literary public games based on the principles of this openness. For instance, we have two teams with opposite views, they go to a forest (visually, the practising of this game reminds me of performances by Russia’s Collective Actions) and there they represent “steps” towards resolving their antagonism. Each “step” should make their position more and more open. I am sorry for any possible misunderstanding in my retelling of Hanson’s approach. I hope my reconstruction is more or less right in general. The idea of open form influenced Grzegorz Kowalski who was Hanson’s student and an assistant in his studio. As we know, Kowalski later used open-form ideas for creating his didactic methods of common and individual space and “education in partnership”. He created an informal artistic group known as “Kowalski’s Workshop” (or “Kowalnia” / ”The Smithy”), which included many important Polish artists, like Paweł Althamer, Katarzyna Górna, Katarzyna Kozyra, Mariusz Maciejewski, Jacek Markiewicz, Monika Zielińska, and Artur Żmijewski.

We can trace Hanson’s influence among these artists and the ideas of games and work with antagonisms, particularly in Żmijewski’s practices. Although for Żmijewski this work becomes a head-on collision and loses its original nuances. In my opinion already in his works we see the emergence of these “new others” or “angry spectators / participants” of the artistic process, for example, when he confronts supporters of ultra-right political views and left-wing activists, offering to resolve their differences through art. No real resolution happens. But there is a birth of art about this impossibility.

So Polish curators decided to take this approach to the institutional level. In particular, they included works representing nationalist ideology in their exhibition halls by way of an experiment for the purpose of critical discussion. The irony of the situation, which returns us to the topic of this conversation, is that under current political circumstances a thing that started as a radical curatorial experiment tends to become a new norm. At least, the conservatism of cultural policy in Poland pushes art museums in this direction.

VD: Yes, basically, if we agree that the internationalist globalist project of contemporary art is over because it is no longer supported by us – even we, professionals, cannot support this globalism. Or we can say that this project fell victim to different nationalist agendas or separatist agendas, be they islamophobic (in the case of Marseille) or coming from other communities. Then we have to agree that there is no possible artwork to be made that could override this sectarianism. But I think there are artworks that could possibly go beyond that.

ML: Internationalism, collectivity, experiencing art, or having an encounter with art, is all morphing, just as it was always morphing: whether for some time there was a blossoming of apartment exhibitions in a particular context that you are very familiar with, or in other situations art moved outdoors, into forests, for example. The angry viewer is also the official whose job it is to limit you as an artist or curator, or to prevent your activities. But most importantly, things have changed continuously. This is really interesting, in and of itself. Coincidentally, on 1 January 2020, I started a project on Instagram called @52proposalsforthe20s, with fifty-two artists making weekly proposals for the new decade. It is now in its second year. Obviously, I did it not know what was going to happen with the corona virus, but the project turned out to be super timely. As someone who has travelled the world extensively as part of my work, I have rarely felt so intensively connected internationally as when I am working on this project. The artists come from many corners of the world, and people who are experiencing their work on Instagram are also dispersed on the planet. On the screen, on the device, in your pocket. All proposals and all viewers – here the term feels right (!) – are simultaneously particular and general, zero viewers and angry viewers.