The cultural reality following 1989 in the former Yugoslavia was framed by constant social, economic, and political crises that persist to the present day. The crises culminated with the Yugoslav war of disintegration, but also continued through the socio-economic transition from socialism to liberal capitalism. The process of transition, described also as a process of failed democratization, was marked by strict regulation of the public domain, including the sphere of arts and culture. Through the control of cultural production, the post-Yugoslav political establishments of the 1990s transformed museums and other cultural institutions into tools of ideological warfare, where sanctioned nationalist visual culture was deployed in overwriting the supranational Yugoslav identity. However, the alternative scene that developed in parallel with this responded with various initiatives in an attempt to preserve pluralist thinking and counter the militaristic and chauvinistic narratives that were proliferating. These initiatives included artist and curatorial collectives, projects, NGOs, and other platforms for critical engagement and knowledge production, including artist-run spaces and museums created by artists. While existing in exile, or outside of the main cultural grid, these museums grew their collections from personal and found objects, public symbols, stories, and actions, mixing them in an effort to create productive strategies for critical engagement with the dominant cultural and political discourse.

Taken as the starting point for this article is the exhibition held in the ruined building of the Belgrade City Museum in 2016, Upside-Down: Hosting the Critique, where many of the museums of relevance to this article were showcased in the form of textual placards and images, including Homuseum (Škart group), Yugomuseum (Mrđan Bajić), Inner Museum (Dragan Papić), Metaphysical Museum (Nenad Bračić), and Rabbit Museum (Nikola Džafo). These museums challenge the restrictive definition of the term ‘museum’ through the social, activist, and performative practices of their authors. Although materially heterogeneous, these museums correspond organizationally with the classical institution and use its structure and name as a critical point in their conceptual explorations. Some of them have also used official institutions as their temporary display location, complicating the understanding of art activism and alternative art practices.

This article addresses the relationship between official and alternative institutions, art projects, and initiatives in times of crisis, with a focus on post-socialist society and artist-created museums. The aim is to broaden the scope of understanding of meaningful art engagement with oppressive systems and those in crisis, marked by “historic revisionism, nationalism and rampant capitalism”. [1] Through a close reading of the selected museums, their role within a wide range of alternative practices will be elucidated, and a new theoretical framing for their understanding will be proposed. Being artworks, but also institutions in their own terms, the selected museums become spaces of exiled artefacts, memory, and actions that gain agency through institutionalization.

The Collapse of Yugoslavia and the Crisis of Cultural Institutions

The collapse of socialist Yugoslavia, resulting in the first armed conflict in Europe since the Second World War, was put in motion decades earlier than is usually understood. Although Yugoslavia’s disintegration formally began when its republics, first Slovenia and soon after Croatia, declared independence in 1991, the political and, more importantly, economic changes that would lead to disintegration started in the early 1960s. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was established in 1945 with six republics (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia) as its constitutive parts, and its people deemed equal under the banner of brotherhood and unity. A Yugoslav identity that transcended the ethnonational one then stood as the unifying principle upon which Yugoslav national culture and politics were built. The country was governed on the principles of equal opportunity, free medical care, free education, a planned economy, self-management of workers, antifascism, and non-alignment. The system of self-management contributed to the development of the socialist production model while centralized economic organization served to consolidate balanced regional development. [2] However, the changes from 1961 onward, with the technocracy pushing for a decentralized system of investments and foreign trade in place of a centralized and controlled one, led to the disarticulation of the Yugoslav economy, with the westernmost republics being better prepared for this change. [3]

The decentralization of the economy and opening up to foreign markets — which included a devaluation of the national currency and deregulation of prices in order to make Yugoslav industry more competitive — are the staples of market socialism that was developing in this period. A new Constitution in force from 1974 furthered the processes of economic disarticulation, with the republics gaining more independence in decision making regarding economic issues, and increasingly acting as individual players on foreign markets. This process of partial capitalist restoration and a slow liberalization of the market also saw a rise in internal conflicts, with each republic fighting for economic dominance over the others. [4] The republican bureaucracies consolidated their influence by assuming the role of national protectors, in what was predominantly an economic struggle, thus moving the conflict to an ideological field of national identities instead of dealing with structural problems. [5] As political economist Dimitrije Birač concludes in his elaboration on the processes of privatization in Croatia, it was possible to achieve capitalist restoration in Yugoslavia only through the mechanism of national states. [6] Coupled with further economic decline during the 1980s, this created a background from which the latter conflict and Yugoslav disintegration ensued. The collapse of Yugoslavia, although prompted by economic decline and the internal struggles for economic domination, was played out in the field of identity politics. The negation of Yugoslav identity, and assertion of the national one, happened in all the republics simultaneously. Nationalist rhetoric worked to actively erase any ideas about cultural continuation between Yugoslavia and the newly formed states, and proposed a different framing of national identification, one going beyond and excluding Yugoslav history and its values. [7] In Serbia, for example, this meant a return to the distant Middle Ages and the first Serbian medieval kingdom as the national signposts. The changes reflected a broader climate of re-traditionalization, where nationalist, patriarchal, and militaristic values became the markers of a new cultural climate, present in media, publications, public talks, and other forms of public engagement. [8] In the field of the arts, the described changes led during the 1990s to the disintegration of the Yugoslav art space as well as the enforcement of national identity and divisions in this sphere too. [9]

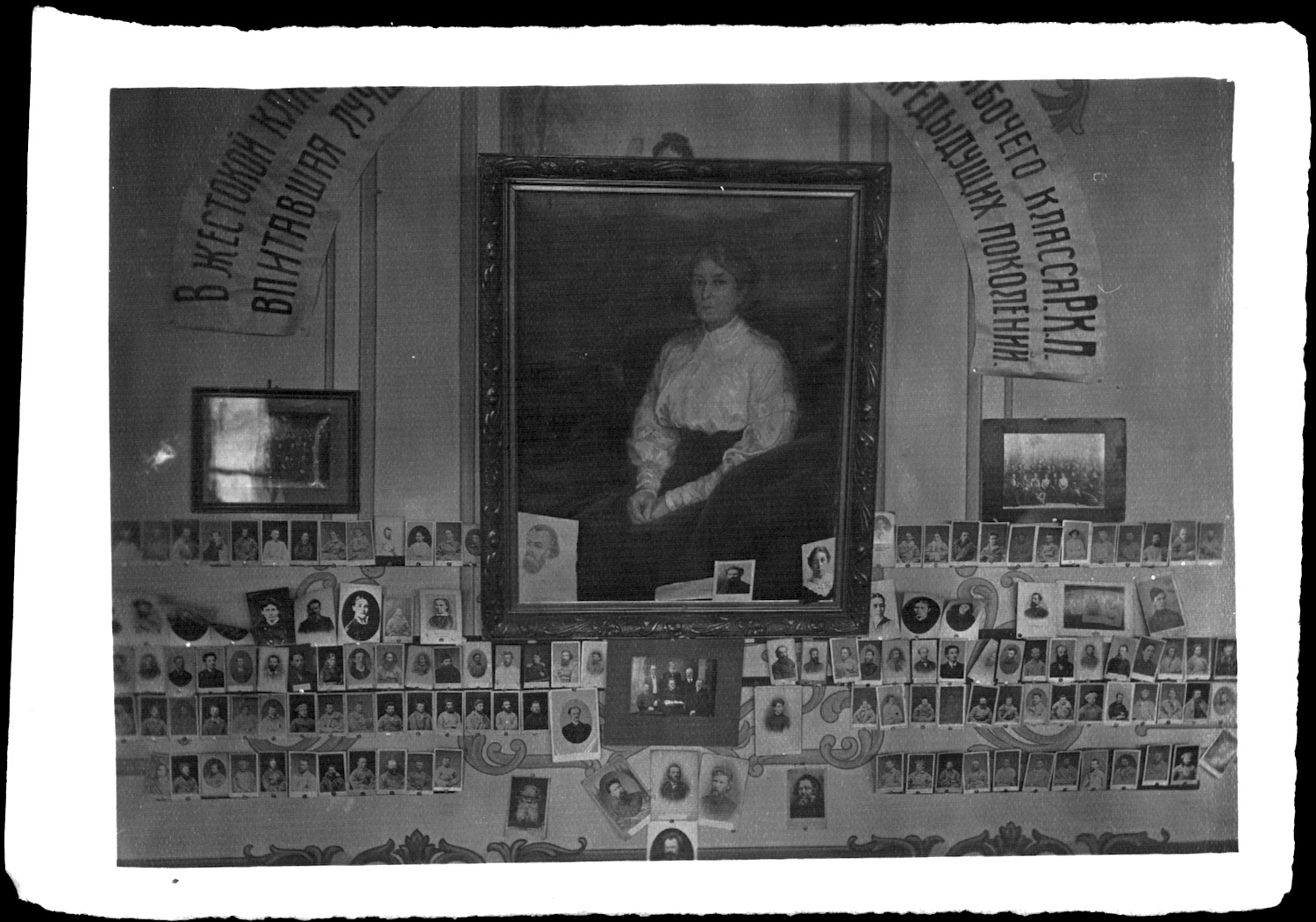

Major shifts in the museum practices of the dominant cultural institutions also happened along the lines of a search for national identity and culture that would overcome and relegate to history the Yugoslav past. One telling example is that of a group exhibition held in the National Museum in Belgrade in 1994, named Balkan Sources in Serbian Painting of the 20th Century, which was critically described as a sum of ethnic, national, and Christian symbols and myths that corresponded with official cultural politics steeped in nationalist and conservative values. [10] Belgrade’s Museum of Contemporary Art, although not directly invested in the new cultural politics through exhibition practices, nevertheless participated in the process by its self-marginalization, with minimal production and participation in cultural life throughout this period. [11]

With a lack of critical institutional response to the changing reality, alternative cultural initiatives started to appear in all former Yugoslav republics. They provided platforms for alternative voices, anti-war and anti-militaristic, to be heard, albeit within a limiting circle of activists, artists, and the informed public. Some of them went through the institutionalization processes themselves, such as the Center for Cultural Decontamination in Belgrade, founded in 1995, the Metelkova centre in Ljubljana, Konkordija in Vršac, Barutana in Osijek, and the Rex centre and Remont gallery in Belgrade, among others. [12]

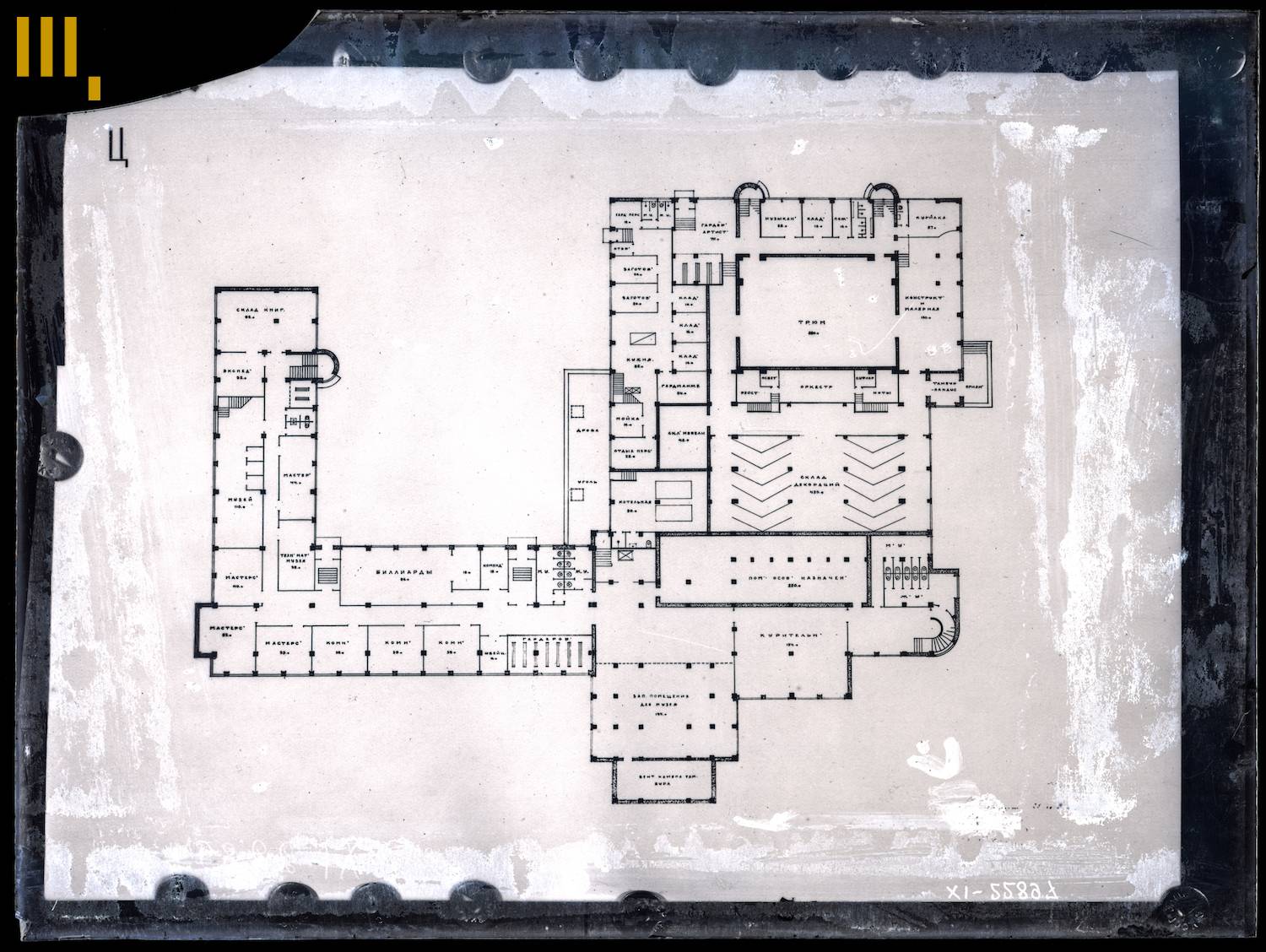

Following the war, the art scene during the early 2000s was affected by the closing of two major museums in Belgrade, the National Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art, due to reconstruction. For over a decade the doors of these museums remained closed, and large-scale exhibitions and retrospectives had to be either postponed, downsized to fit smaller gallery spaces, or moved to institutions with a different primary focus. At the same time, other institutions and galleries, such as the Museum of Yugoslav History, gained prominence with their shows, and even dilapidated buildings such as that of the Belgrade City Museum became new art hubs. Alternative spaces also proliferated, one of them being Inex Film, based on the premises of a former import-export company that closed in the 1990s. This building was transformed into a squat place for young artists, and contained several art studios and an exhibition space. [13]

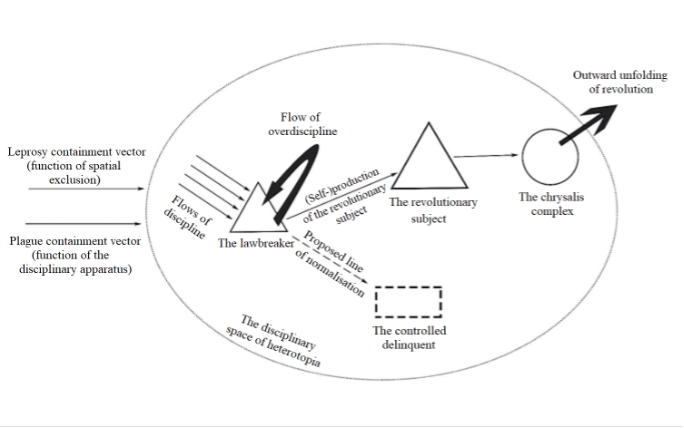

Alternative institutions did not just include those with a fixed location or structural organization resembling an institution, but also initiatives which used the terminology, structure, or other elements of an institution to engage in critical work, but which did not operate as classical institutions per se. [14] They represent one of the many forms of critical engagement with art institutions that proliferated in the former Yugoslavia and the broader region of Central and Eastern Europe following the collapse of communist regimes. Initiated by art professionals, these practices searched for alternative possibilities of functioning within the system; of being present but changing the spaces of display on an ongoing basis.

Hosting the Critique

Among the first systematic presentations and analysis of the relationship between the official museum institution and its alternative, artist-created museums and practices in the former Yugoslavia, were the exhibitions held in Ljubljana and Serbia titled Inside Out – Not So White Cube (2015) and Upside Down: Hosting the Critique (2016). The latter, held in the Belgrade City Museum, presented a continuing exploration in three sections of the theme started in Ljubljana’s show – the position and role of alternative, artist-run spaces and institutions, projects, and initiatives in contemporary times of crisis. The three sections corresponded with important questions the exhibitions raised regarding the significance of such projects and initiatives within the institutional art networks, the position of official museums in periods of transition, and the functioning of artists’ museums and their raison d’être.

The first section was initially created for the Ljubljana show. It took the form of a research archive of different artistic practices, exhibitions, and projects created as a response to official practices and institutions. The analysis continued in the second section, dedicated to the complex position of the Museum of Modern Art in Belgrade within the political changes and economic circumstances of a Serbia in transition. At the time of the exhibition, the museum had been closed for several years due to renovations, and the projects commented on this situation. The third section showcased artists’ museums — the alternative spaces for exhibiting artworks, but also for questioning and reflecting on the complex socio-political, cultural, and institutional contexts of art production, collection, and presentation. This section was a showpiece of practices which, created in times of crisis and transition, attempted to disturb the status of the official institutions and memory, and to offer new modalities of thinking about, and acting upon the institutional structures and processes of remembrance. The institutionalization of artist’s initiatives — through naming and organization, but also through presentation within official institutions of culture — constitutes a critical point for interpretation of these works within a broader spectrum of political possibilities.

Museums, being never neutral spaces for displaying art, produce narratives, histories, and values, and “frame our most basic assumptions about the past and about ourselves”. [15] They are, like any other institution, conditioned by socio-political, cultural, and economic circumstances. The institutional importance and prestige of museums have often been (mis)used in support of various different political and cultural agendas, with their seemingly neutral position being a fruitful ground for establishing normative narratives on culture and identity.

As an alternative, a more transparent and power-sharing museum institution has been theorized in recent decades. The new institution should unpack the assumptions about a museum’s neutrality and become a site of “discourse and critical reflection that is committed to examining unsettling histories with sensitivity to all parties”. [16] The idea of a critical museum in the context of Central and Eastern Europe has been proposed and analysed on the example of the National Museum in Warsaw by art historian Piotr Piotrowski. [17] His definition of a critical museum as a museum-forum, open for public debate on important issues from the past and present, emphasizes a self-critical stance as crucial in its functioning. [18] Institutional critique developed from within an institution is an important aspect in the restructuring of museums into democratizing, dialogical tools; a position that is particularly significant for the former socialist states.

However, the position of museums as normative institutions in the context of the historical reframings and nationalist discourses of the post-socialist countries limited the scope of possibilities for critical interventions. The status of these institutions as public and being funded by the state, influenced the development of different modalities of institutional critique than those created in the liberal capitalist societies. [19] While in the West institutional critique was ‘institutionalized’ from the 1960s onward, in the post-Yugoslav context such interventions were manifested primarily through artistic works and actions that were marginalized in art discourse, or downright ignored. [20] Art historian Maja Ćirić makes a distinction between art practices that were ignored by the art system and therefore failed to broaden the scope of the art field, and those that were presented at review shows, such as Upside-Down, or supported by institutions themselves. [21] These practices enter official institutions, but their critical potential is deemed appropriated and subdued in the creation of postmodern plurality.

Institutional critique as a radical protest against the established art norms and structures of circulation and presentation of art — enacted through art practices but also in the form of pickets, boycotts, blockades and occupations of institutions, and other forms of public dissent — is often institutionalized, such as in the symposium “Institutional Critique and After” that took place at the LA County Museum of Art in 2005. [22] The critique of such practices is aimed at their political potential, which seems to have been co-opted by the institutions these practices reacted against, and thus rendered ineffective. Agency is attributed to the formats that stay outside of the institution, which, when co-opted, lose their political efficacy. However, the art institution, when understood as a broader concept including the “entire field of art as a social universe” [23] widens the scope and effectiveness of critique, and provides a more generous framework for a reading of art’s political and cultural significance.

As artist Andrea Fraser proceeds to analyse, the institution of art is established not just through institutions and practices, but also through the modes of perception and other competencies that allow each individual to recognize art as art. Therefore, the outside of the institution cannot be achieved either through physical removal from it, or through conceptual and theoretical existence outside of it. It is internalized, and therefore institutional critique can only come from inside of the institution itself. [24] This, however, should not devalue institutional critique. Instead, the institutionalization of the institution of critique, as explained in the example of the failure of the project of historical avant-gardes, is a site of political action. As Fraser explains: “Recognizing that failure and its consequences, institutional critique turned from the increasingly bad-faith efforts of neo-avant-gardes at dismantling or escaping the institution of art and aimed instead to defend the very institution that the institutionalization of the avant-garde’s ‘self-criticism’ had created the potential for: an institution of critique. And it may be this very institutionalization that allows institutional critique to judge the institution of art against the critical claims of its legitimizing discourses, against its self-representation as a site of resistance and contestation, and against its mythologies of radicality and symbolic revolution.” [25]

Thus understood, the potential of ‘institutionalized’ institutional critique provides a highly productive framework for the interpretation of self-institutionalizing practices of artists from the former Yugoslav space. Their practice can be broadly defined as emerging “from a belief in organizing new programmes and activities to combat constraining political, social, economic and cultural conditions” — a definition of self-institutionalizing as proposed by art historian Izabel Galliera. [26] Talking about the different context of Central and Eastern Europe, particularly of Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, she analyses the political agency of the dominant initiatives and models of self-historicizing in this region. Although her focus is on initiatives other than artists’ museums, such as the artistic initiatives DINAMO and IMPEX from Budapest, 0GMS project from Sofia, and the organization Department for Art in Public Space in Bucharest, there are broad similarities in purpose and engagement with the museums discussed here. The mentioned initiatives worked as alternative and discursive places that questioned “the rewriting of recent past … and engaged in self-reflexive and sustained forms of critical discussion on the recent socialist past, on what ‘leftist’ thinking could mean in a post-socialist context and on the role of local institutions dedicated to contemporary art”. [27]

Artists’ museums also engaged, in their own particular way, with aspects Galliera describes, specifically those relating to the re-examination of the past and self-reflective positioning within the art system and its institutions, as the following close reading of the works will show. The Metaphysical Museum of Nenad Bračić archives and historicizes Bračić’s art practice, similarly to the practice of IMPEX that focused on the local alternative art scene. Satire as a strategy was deployed by 0GMS in institutional critique and is also a recurring theme in Yugomuseum by Mrđan Bajić, Rabbit Museum by Nikola Džafo, and the Inner Museum by Dragan Papić. In addition, talking about the past and questioning the politically sanctioned narratives about it constitute one of the dominant aspects of these initiatives and museums, and reflect a broader interest among the artists and art workers of Central and Eastern Europe. While the mentioned initiatives functioned more-or-less as community centres and platforms with various programmes, artists’ museums were focused on artworks and their creation as well as on display in virtual and real places. However, both models of engagement with art institutions and broader political issues positioned art at the centre of political struggle and emphasized various modalities of art’s political potentialities.

Yugomuseum (Mrđan Bajić)

This museum does not need halls and walls; you

do not need to purchase a ticket to gain admission.

You move about in it at no cost every day, whether

you want to or not… [28]

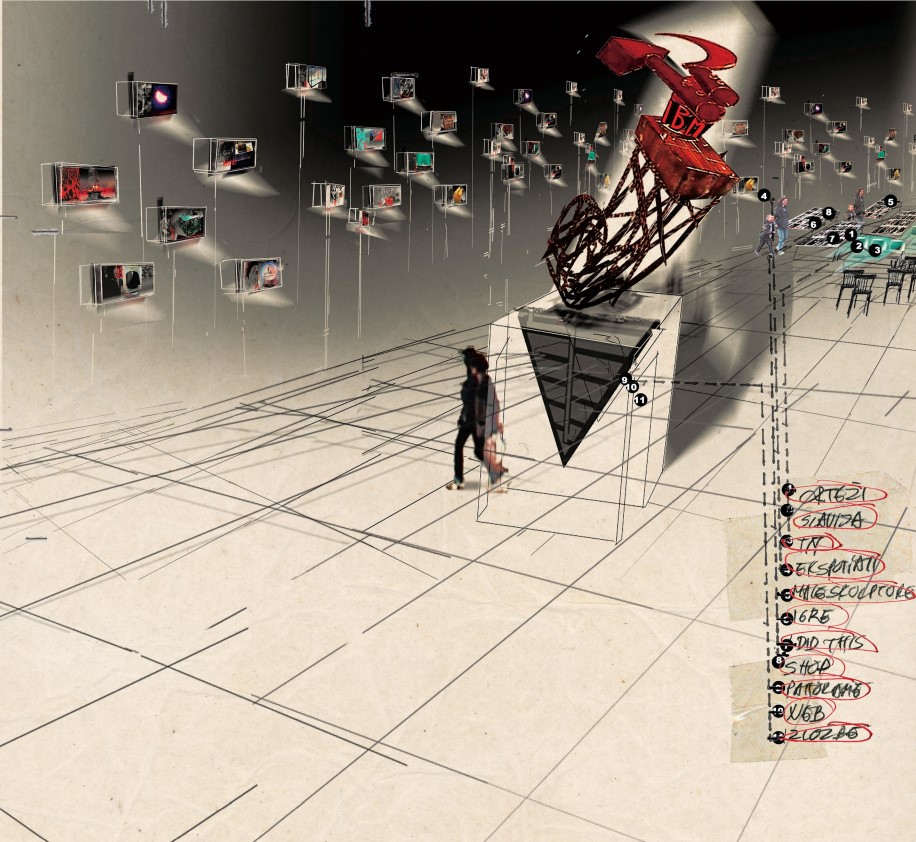

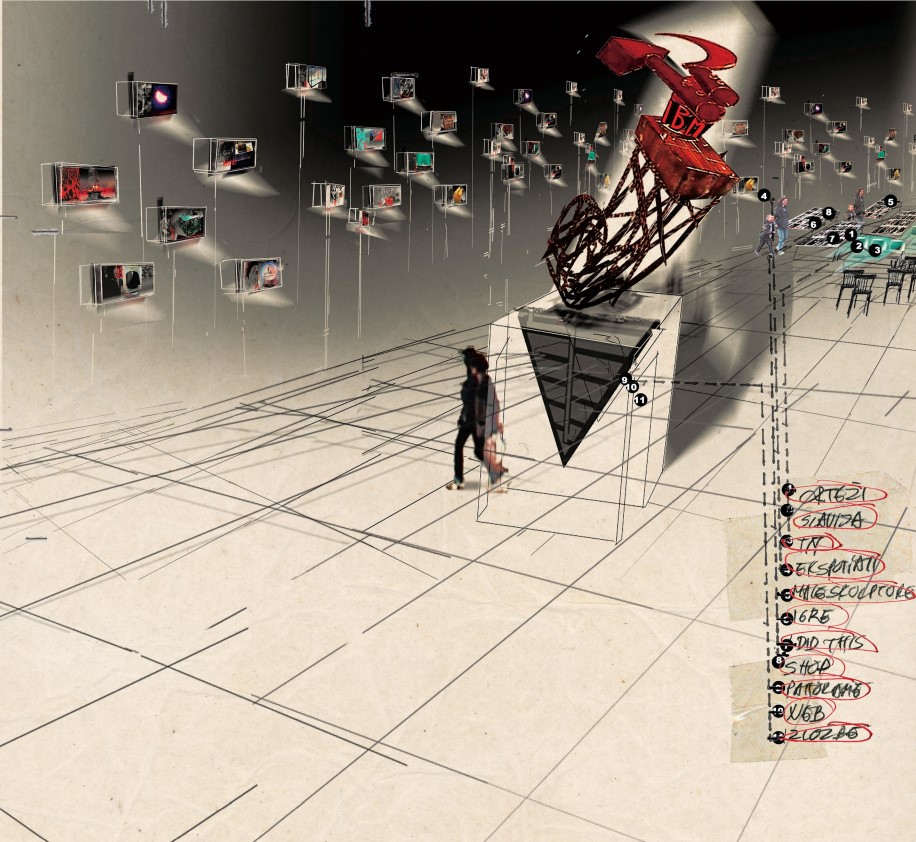

Yugomuseum, a multimedia project by sculptor Mrđan Bajić, developed over several years, starting from the initial ideas and experiments in 1998. The first international presentation of the project came in 2002 at the 25th São Paulo Biennial, and was later included in the exhibition Project Reset at the Venice Biennale in 2007, as part of the display in the Serbian Pavilion. [29] It was the first time that Serbia had appeared at the Biennale as an independent country, following the breakup of the Serbia and Montenegro union in 2006. Bajić had previously been selected to present his work at the Biennale in 1993, but due to the sanctions imposed on Yugoslavia by the international community, which included a ban on all cultural exchanges, his participation was cancelled. [30] The re-selection of the artist in 2007 symbolically marked the beginning of Serbia’s independent participation at the Venice show; a general attempt to reset its culture, and a personal resetting for Bajić himself. [31] Project Reset was a three-part display with sections named Yugomuseum, Back-Up, and Reset occupying the space both inside and outside of the Yugoslav Pavilion. [32] Yugomuseum, positioned at the entrance in the form of a time capsule with a sturdy, architectural form opening up towards the doorway, hosted a video presentation of the museum’s exhibits. This represented an archaeological excavation of memory, from the position of a disenfranchised subject that had lost its point of reference with the disintegration of Yugoslavia. The ironic, surreal, and emotionally charged works seem to be patched together from the uncertain and wavering memory of this subject; a memory that oscillates between contradictions of the Yugoslav past — of its praise, condemnation, and erasure. During the 1990s, Yugoslavia became throughout the region a symbol of a lost time when national identity could not be expressed and exercised fully, and therefore the national consciousness and culture had failed to come into being in its imaginary completeness. The lost time had to be compensated through rapid national mobilization in the 1990s, meaning that the past needed to be erased as a point of collective identification.

Fragments of the Yugoslav past — its symbols, objects, images, and other memorabilia — are mixed in Yugomuseum with the contemporary moment and its visuals, including fragments from the nationalist mobilization that resurface the uneasy memories of violence, hatred, and crimes committed. The Yugoslavia from which the memorabilia derived is thus not just the socialist, federative, post-Second-World-War Yugoslavia, but also its predecessor and successor — the Kingdom of Yugoslavia as its ideological antipode, and the Federal Yugoslavia created from the union of Serbia and Montenegro in 1992. [33] Although it references a concrete historical period, Yugomuseum goes beyond the representative historical framework, and instead transforms the history into an aesthetic experiment in Bajić’s “sculptotectural” manner.

Sculptotecture (skulptotektura in Serbian), a term used to describe the artist’s works, combines sculpture and architecture into one. [34] As a hybrid form of expression that draws from both models of creative production but subscribes to neither, it is characterized by the tension between their different principles, such as “reduction and construction, imagination and rationalization”. [35] Developed over the years, starting from the artist’s early experiments in the 1980s, sculptotecture finds its expression in the Yugomuseum as well, as one aspect of this complex work. Yugomuseum had evolved over the years, from materials gathered through email correspondence and the construction of artefacts, into a unifying model at Venice, where the museum is present through virtual display and the concrete form that hosts it.

Yugomusem passed through four phases of artistic explorations, starting with the early email correspondence between the artist and his friends, acquaintances, and collectors. The artist sent images, digital works, and collages of the objects he had designed, and gathered comments, photo contributions, essays, and reactions, developing his ideas further through this practice. The second phase included a presentation of the museum through public talks in several cities. At these talks, Bajić described the museum and its exhibits, and included images as well, to complete the illusion of the museum as a real and physically existing place. In the third and fourth phase, the artifacts were created and shown in several exhibitions, followed by a web presentation of the museum at www.yugomuzej.com. [36] The full scope of the museum includes a shop, library, an archive, and a children’s corner in its virtual space. [37] The final project consists of 52 artefacts (although new artefacts could be added) that are described in detail by the artist. These descriptions add detail and help in understanding. For example, the text for one of the artefacts reads as follows:

*040: Parade. 900×600×1200cm, 2001.Wood; cardboard; youth, workers and the honest intelligentsia; a hammer and sickle, woven from red carnations; the inscription: ‘Brotherhood and Unity’; the coat of arms of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and its republics on a movable platform which was a part of the 1st May Parade in 1957. Donated by Bagat. [38]

Such descriptions help those less versed in Yugoslav history and its symbols to understand the complexity of the works, the museum as a whole, and also the great mass of historical material that has been put through various interpretations. As the artist stated, the museum developed over time and was literally developed by the time in which was created. [39] It seemed like a good idea, as he stated further, that the time of lies and false historical memory might be reflected in an imaginary institution that would decentre the dominant narratives about the past, and include personal memories as a mockery of the “large and horrifying history”. [40]

The lines of interaction between the museum and its visitors are transposed onto the level of the artist’s impressions, memories, and aesthetic choices, where narratives, associations, and affective reactions derive both from personal recollections and from artistic choices in creating complex visual symbols. The important moment was the inclusion of supposed future visitors in the creation of the artefacts through email correspondence. In this way, the artist created Yugomuseum as an art space of personal and collective transformation, where past truths, events, and symbols could be revisited, questioned, and problematized. By showing the historical material through the prism of personal experience and personal artistic practice, the museum’s existence as a normative site of knowledge, a site the institution of the museum has held throughout history, is abandoned and the status of its supposed historical neutrality is reviled as a fallacy. The aesthetic component, of being a personal vision of history to which it belongs, made of fragments brought together in sculptotectures, further visually and conceptually decentres the museum from the position of a historical narrator. It shows instead the personal truths of an individual, caught up in the makings and unmakings of various Yugoslavias, who seeks to find their own space of understanding and meaning.

The Inner Museum (Dragan Papić)

Dragan Papić, an artist of diverse and prolific output, began collecting various everyday objects in 1976, and over the years his collection grew significantly to the point that he decided to present it in the form of a museum, named the Inner Museum. As he explains, work on the museum started in late 1993, and he named it the Inner Museum as a concluding point in its development. [41] The decision to name the collection a museum represents a play on the meaning of this institution and its significance regarding collective knowledge and processes of remembering. The collected objects are arranged in unusual, surreal, and awkward ways, aesthetically resembling a contemporary cabinet of curiosities and “an archaeology of the rubbish dump”, through which personal and collective memory is contrasted, analysed, and communicated. [42] The meaning of the objects is decided by the artist, as is the logic of the arrangement, but it remains almost impossible to decipher them without the artist’s explanations.

The museum is located in the artist’s flat in Belgrade, and therefore — in contrast to other museums of interest here that do not have a permanent location or were temporary — has a physical location that can be visited. Over the years, the collection grew to the extent of hundreds of objects, seeped out of Papić’s flat, and took possession of the communal spaces in the building, including entrance halls and staircases. This led to a dispute with one of the residents in 2007 and a collective action by other artists to preserve and protect the museum. [43] Although present on the cultural scene for many years, the museum was officially recognized as a site of cultural significance in Belgrade only in 2010. [44] It was open to visitors by appointment until 2007, and today it occasionally opens its doors to researchers. A selection of exhibits from the museum was displayed at the 44th October Salon in Belgrade in 2003, under the title Fragments of the Inner Museum, for which the artist won the Salon’s award. The museum was also included in the selection of the Salon in 2006 by the curator René Block. [45] For the 2006 exhibition, the museum was open to visitors at its location, turning a private flat into a public space for five weeks.

Collected over time, the objects in the museum acquire meaning as carriers of memory about the socialist Yugoslav past and broader global events. They resemble a mausoleum of the visual memory of Yugoslavia and its aftermath — an undesirable recollection during the processes of nationalist mobilization. Various porcelain figurines, dolls, toys, decorative plates, Yugoslav souvenirs, Yugoslav symbolic objects, kitsch paintings, and other memorabilia were collected from the streets, dumpsters, and flea markets, testifying to the marginalization of narratives and the memories they represented. Their significance is reestablished through the context of the display, but outside of the museum as their cohesive element, these objects would probably find their way back to the marginal places from which they were collected. The action of bringing them to the centre of attention in a museum-like setting is a critical gesture of rethinking the value of art and more generally of what can be art in the context of the past and present. Memories, through artistic intervention, are collected and collated to create a network of often confusing visual artefacts which, through the process of naming, gain their critical potential and artistic value. The absurdity and confusion of their arrangements combined with their sheer number punctuate the surplus of memory left unacknowledged by the official memory politics. Although many of the artefacts stand for events and people that were present in public narratives, the artistic intervention puts them in relations that clarify and accentuate the problematic aspects of their past that have been removed from public discourse.

For example, one of the artefacts named Storm after the military operation in Croatia during the Yugoslav War consists of toys in the form of an elephant, dog, and a human figure. These toys are named Stjepan Mesić (the human figurine dressed in Austrian/German folk costume), Ratko Mladić as the dog, and a collateral victim as the elephant. Mesić, the last holder of the Yugoslav Presidency and later Croatian president, next to Ratko Mladić, a war criminal and a leader of the Republika Srpska army during the conflict, stand over the toppled victim, creating a grotesque tableau vivant. [46] Drawing on memories about these persons, the tableau puts uncomfortable histories together, which, through the level of association, open a space for dialogue and critical examination of the past events. The Inner Museum of the artist works also as his inner space; his metaphorical body that is reflected also through self-portraits he concocted with the help of kitsch paintings of a crying boy that were once widespread in Yugoslav households. He transforms them with the addition of reading glasses inserted into the painting, creating a combination of painting and sculpture. These artefacts, created during the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, testify to the affective level of the museum, where histories and memories are not just cognitively dissected, but are also addressed through the visceral, emotional level and transposed into objects of symbolic value. The Inner Museum, working both on the individual and collective level, stands also for the inner, invisible part of an institution; an unacknowledged depository of rejected visual materials, removed to the margins of recollections.

A dialogue between visitors and the artist inside the museum is a crucial element of its function, as the inner vision of the artist and the associations, histories, and stories he creates come in contact with others who experienced the same period and can elucidate its various aspects. Thus, the museum, as the artist’s home and a reflection of his inner self and the memories he carries, is contaminated with other memories and visions, in a performative act of past reevaluations, dialogue, and critique, with points of ideological and political contacts between the past and the present materialized through artefacts as “symbolic guides”. [47] The museum forms a “performative archive” where names given to objects, the compositions they make, and the interaction with visitors create a “multidimensional field of memory”. [48] Visitors encounter fragments from their own past, rejected from the official institutions of memory, and can engage with them, discuss with the artist, and remember. The unusual collation of objets trouvés, and their metamorphosis into art reverses the role of artefacts as ideological signifiers into objects of critique, satire, and unexpected encounters, reflective of the complex positioning of local histories, narratives, and ideologies within the global context.

Metaphysical Museum (Nenad Bračić)

Metaphysical Museum was founded in 1995 by Nenad Bračić, and it consists of the artist’s works and projects he has realized over the years, including: Photographs 1980–1985, The Tale of Kremzar’s Finds (1988), Sacrifice (1993–1994), The Objects of Unknown Usage (1989), Contributions to the Metaphysical Museum (1995–ongoing), Metaphysical Library, Photo-Cine Equipment (1998–2004), Do You Remember Me (2007), and Chopping Boards. The museum is not dedicated to a certain theme, or the artist’s recollections and memories, as in some of the other museums analysed here. Instead of showcasing a particular set of artefacts within a dedicated space, virtual or real, the museum is comprised of all the works and projects the artist has created, and is a unifying trademark for his diverse output. As Bračić explains: “Since I work with a variety of media, and since this scene generally requires a particular kind of recognition, I institutionalized my whole opus under the term ‘the Metaphysical Museum’.” [49] Created on the level of language, the museum is a marketing tool that is envisioned to help Bračić and his work gain broader recognisability and currency. [50]

Bračić has created a brand for himself and his work that would be recognizable but that would also legitimize his urge to collect, which, as he asserts, is an urge widely present among contemporary artists. [51] Metaphysical Museum, as a brand and also an imaginary institution not linked to a material location, is present wherever and whenever the artist and his work are present as well. A lack of physical space did not prevent Bračić from conceiving a museum with all the institutional perquisites, including a secretary, a spokesperson, a seal, and even a photograph of the building. [52] The museum can exist virtually, as an Internet presentation or website, but also in the artist’s studio, or any other location containing Bračić’s works.

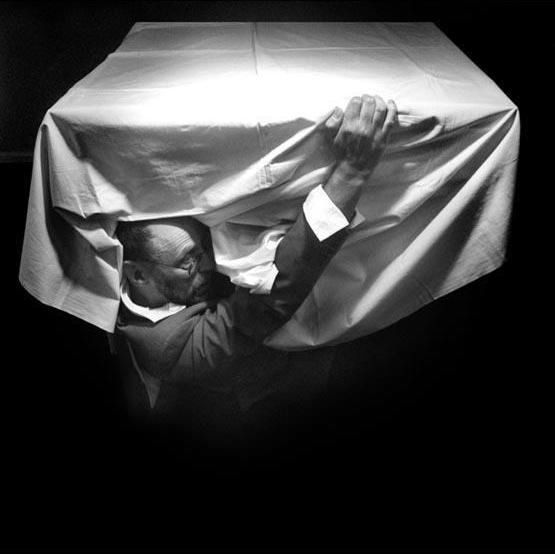

The metaphysical nature of the museum corresponds not just with its immaterial, imaginary form, but also with the artist’s sentiment in creating works; a sentiment of “seeking dreams and constantly creating illusions”. [53] Bračić’s opus is diverse and spans several decades – decades that saw changes in the materials he uses, such as the shift from bricks to wood, and a change in forms, from experiments in photography to interventions with ready-made objects, and the creation of pre-devices as a play with existing forms. These pre-devices, or pre-apparatuses (preaparati in Serbian) as the artist named them, feature in the cycle Photo-Cine Equipment, and resemble in form other already-existing devices, but are fashioned from much more widely available and cheaper materials. The series of pre-apparatuses named Sory includes the rendition of different photo and video cameras in non-standard materials such as bricks, wires, and old wheel frames, giving them a rustic and archaic character. The referential play is emphasized through name tags attached to objects with the name Sory (resembling Sony) embossed on them. A thread clearly visible in Bračić’s work is his interest in cheap found materials and everyday objects, which position his opus in the traditions of Arte Povera and the ready-made.

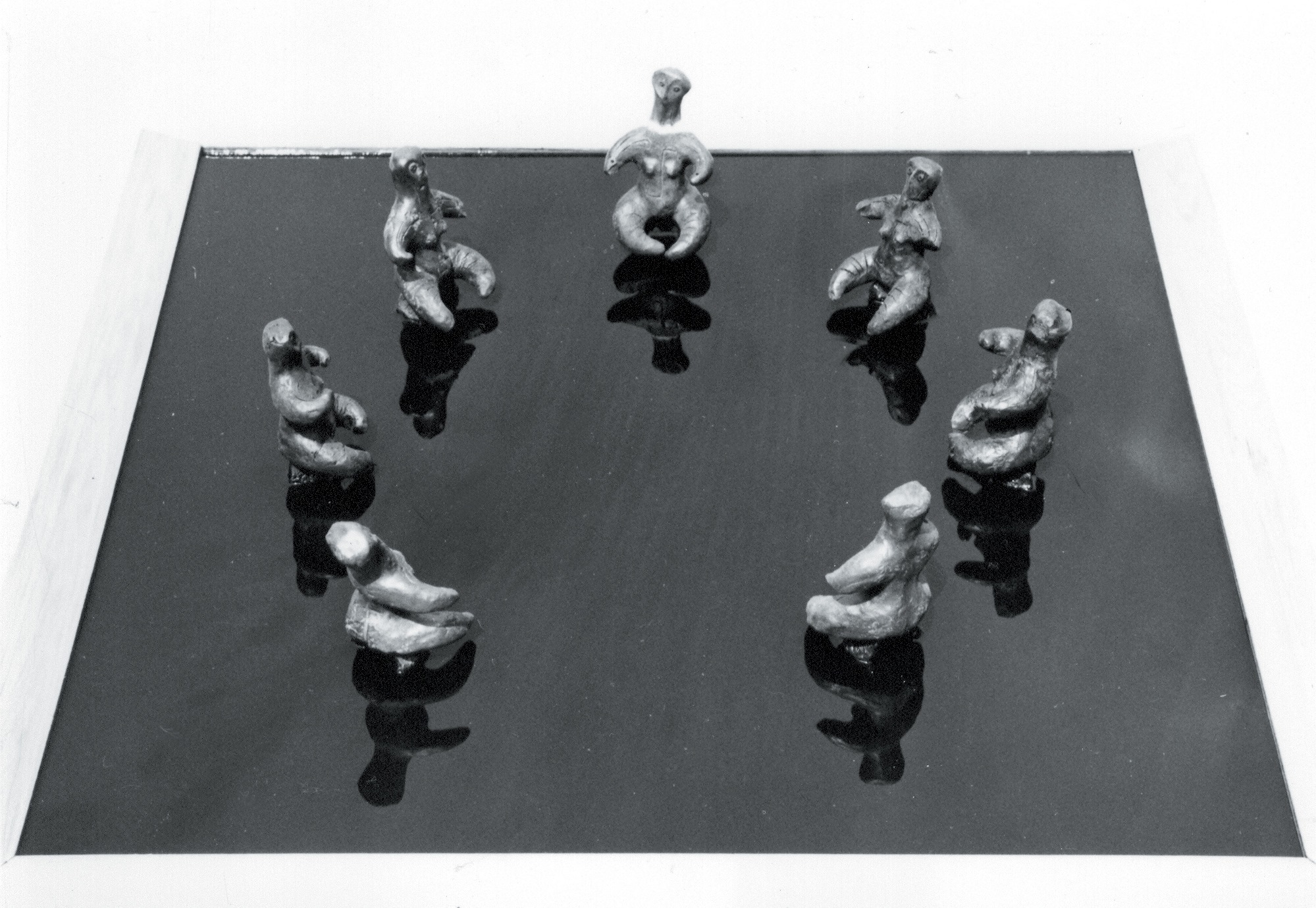

While experimenting with forms and objects has been one of the artist’s defining marks, his other projects show a broader take on the role of art in ‘creating illusions’ and include the use of various art forms in a single work, such as text, photography, and sculpture, in achieving Gesamtkunstwerk. In The Tale of Kremzar’s Finds from 1988, Bračić came up with a story about an archaeological discovery, through which artworks he had created were presented as ancient artefacts and long-lost objects. A similar artistic project exploded on the global art scene with Damien Hirst’s Venice exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable in 2017. Described as the art for the post-truth world, Hirst’s exhibition was a super-show of tremendous dimensions that raises questions about the value and purpose of art in a highly commercialized art market. [54] Decades prior to Hirst, Bračić had created a narrative of lost objects and forgotten past that he helped bring to light. He conceived the imaginary archaeological site of Kremzar, a neolithic settlement with a dubious history, and created artefacts with strong historical and art historical referential importance. The Kremzar excavations, as he narrates, were started in the 1960s by his amateur archaeologist grandfather. Among the discoveries were a swastika-shaped object with horns from the Bronze Age named Clothing Hook (1990), along with phallus-shaped bronzes, some of them with a rotating swastika or horns on top. [55] The Clothing Hook was created later than Kremzar’s other finds, but is included in the project that evolved over the years. The location of the discoveries was presented via an aerial image of the excavation site, its layout forming a Greek cross whose endpoints are four tombs with phallus-shaped tombstones, creating once again the outline of a swastika. [56] Other objects from Kremzar included Venus figurines and various idols. The finds were accompanied with archaeological documentation, drawings, photos, personal correspondence, news clippings, and even a portrait of the grandfather, all invented by Bračić. [57] While Hirst used famous figures and symbols from mythology and popular culture (including Mickey Mouse), Bračić restrains his imagination to familiar forms that resemble true archaeological finds, avoiding any spectacularization of his work, but engaging in problems of historical interpretation and creation.

Bračić’s museum, as the verbalized idea of collating all of his work under one banner, functions as a permanent retrospective that is constantly being enriched with new works. It is at the same time both constantly present and absent, as it cannot be visited in one place, though its objects are nevertheless displayed within its metaphysical space and therefore form part of a permanent collection. The relationship between the visitor and the museum is actualized whenever a visitor observes Bračić’s works. The location is not particularly important; it can be a gallery, a museum, or the artist’s studio. It is everywhere where Bračić’s work is present, expanding on the idea of a museum as a spatially fixed location. Just as history cannot be contained within one dominant narrative about the past, but can have many iterations, so can a museum be an imaginary site of personal choices and preferences, where musealization happens in cognition only.

The Rabbit Museum (Nikola Džafo)

One of the most perplexing museums created by an artist is Nikola Džafo’s Rabbit Museum. Exhibited for the first time in 2006 under the title The Rabbit Who Ate a Museum, the collection consists of artworks, various objects, and toys that repeat the motif of a rabbit, which the artist has collected or created over the years. The museum also has an opera piece and a book that accompany the collection. Rabbit Museum, still without a permanent exhibition space, reflects the absurdity, destruction, and excess of the times in which it was created.

Nikola Džafo was one of the leaders of the protest and activist art in Serbia during the 1990s and early 2000s, and one of the founders of the Center for Cultural Decontamination in Belgrade, Led Art collective, Art Clinic project, and Shock Cooperative. His career developed from early provocative paintings, showing the decaying life of social margins and the ubiquity of erotic stimuli in popular culture, shifting towards activist art and use of ice, garbage, hair, and finally white paint as his material. The rabbit, as a motif, sneaked into Džafo’s work while he was part of the art collective Led Art, featuring as an individualistic expression developed in parallel with Džafo’s participation in collaborative actions. Over the years the rabbit motif multiplied to give the considerable number of exhibits from which the museum was finally formed.

The first appearance of a rabbit, a living one displayed in a cage, was at the Art Garden exhibition in Belgrade in 1994, and it became a constant theme present in his subsequent shows and actions, such as In Which Bush Does the Rabbit Lie? (1997), Departure into Whiteness (1999), Public Haircutting (1995–1998), Kunstlager (2000), The Rabbit Who Ate a Museum (2006), Lepus in Fabula (2011), and The Garden of Solstice Secrets (2018). As part of the Departure into Whiteness exhibition, the artist asked his friends and visitors to contribute to the show with their works on the theme of a rabbit. [58] His call to the public and friends led to the accumulation of toys, collages, graphics, drawings, and objects that formed the Rabbit Who Ate a Museum collection, first presented in 2006. [59] Described as a rabbit Wunderkammer, the collection consisting of around 2000 objects is divided into several sections: Ceramic, Wood, Miscellaneous, Velvet, Rubber, Small Plastic, Fabric, Artworks, Metal, and Paper/Book. [60] The collection is enriched with a musical piece, Rabbit Opera, and a book from 2000 – The Rabbit Who Ate a Museum. [61] The rabbit is not just a museum prop, but becomes an active participant in political and social life through actions such as White Rabbit for a Mayor (2004), and has been cast in multiple roles; from intellectual and critic, to cultural worker. [62]

The exhibition Departure into Whiteness is considered a transformative point in the artist’s career, due to his making a symbolic break with the past by overpainting a selection of his works in white. The interpretation of this gesture can lead in multiple directions, considering the personal and collective moment, the socio-cultural circumstances, and aesthetics. It marks Džafo’s break with his previous work, and is also an exception from the current circumstances and institutions, with disappearance into white being the ultimate liberation from objectivity and form. Džafo’s motto in this period — “ethics before aesthetics” — seems to reach a final visual expression through this erasure. [63] At a time when Yugoslavia was being bombed by NATO, Džafo removed traces of the past, his personal past but also the collective past, and decided on a radical gesture reminiscent of Kazimir Malevich’s suprematist ideas. Malevich described in 1915 how he had reached creativity by transforming himself “in the zero of form”; this annulment of objectivity meant a new beginning in his artistic explorations. [64] The disappearance of Džafo’s paintings and the appearance of a rabbit as the dominant motif is a nucleus through which the Rabbit Museum can be approached and interpreted. “Permanent questions and dilemmas I have been posing about my creative work: How should one confront destruction and senselessness? In evil times to abandon artwork or to react polemically? Ethics or aesthetics? How should one free him/herself from the produced works, collected objects, how to get rid of the ‘garbage’? … [these,] and many others, placed the RABBIT as a metaphor for all the problems and illnesses of our society, local community, but also joys, successes and pleasures” — states Džafo in his explanation of why a rabbit and why a rabbit museum. [65]

The rabbit appeared when it was impossible to continue as things were; ethical dilemmas led to a questioning of artistic practice and its political potential in times of crisis. By moving his past into a whiteness from which a rabbit appeared as a motif, Džafo searched for an alternative set of symbols that would encapsulate the complexities of the times, without reaching for its visual manifestations. Neutral, but also charged with historical, ethical, social, and cultural significance, the rabbit outgrows any attempt to be restrained with a single coherent theory. It is a rabbit from childhood stories and rooms, from historical paintings and modern performances (Albrecht Dürer’s Hare comes to mind as well as Joseph Beuys’ How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare), but also from folk beliefs and traditions about life and death, from satires about its sexual libido, and many more. [66] It is finally Džafo’s rabbit who ate a museum; a series of exhibitions, actions, and finally a museum, whose historical, political, and cultural significance is eaten by a rabbit. The rabbit clears the museum of its normative and hegemonic deposits of meaning; they are gobbled up, and leave a space for new inscriptions and art. It is a clear space where one can inscribe and search for meaning through the personal coordinates of experience. It is a play that shows that museums and their meaning come from art and our relation to it; we can decide what art is and what forms a museum, even if it is eaten by a rabbit. It is a field of children’s play, of irony and satire, and a stern political critique as well. It is also ambivalent and undecided, recalling the lack of clear and direct institutional opposition to the official politics of the 1990s. Each visitor can find her/his own rabbit in it and contribute to building the museum’s meaning.

Homuseum (Škart group)

The only museum in this group that had a timespan, physical location, and initially no exhibits (virtual or otherwise) is Homuseum (Domuzej) by Škart group. This museum ‘happened’ in 2012, in the form of an occupy action, when Škart group together with other artists, activists, and students took over the Legacy-Gallery of Milica Zorić and Rodoljub Čolaković. The gallery is an external exhibition space of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, and was turned into a space for living and creating art for the period of the Homuseum’s existence. The museum had no exhibits upon its founding, but the artists created art while staying in the gallery. However, the goal in creating this museum lay not in hosting a group of works, but in questioning the inaccessibility of cultural institutions to the public and artists, and an expansion of the understanding of the role of institutions through performative action.

Škart group, present on the Yugoslav and Serbian art scene since the 1990s, developed its practice through combining various artistic expressions, including architecture, music, poetry, fine and applied arts. [67] The group’s early works were experiments in graphics, but soon after the group members started engaging with people — on the streets, in open markets, carnivals, and other spaces of public circulation and gathering. The core of the group is made up of Dragan Protić (Prota) and Đorđe Balmazović (Žole), with the number of other participants changing, depending on the project. The group, or collective as they are also referred to, was founded at the Faculty of Architecture in Belgrade in 1990 with the name Škart (literally ‘scrap, rejects’), taking inspiration from the mistakes they had made in their early graphic works. [68] These mistakes, instead of being seen as negative occurrences, were accepted as markers of a “new system of value” on which the group based its practice. [69]

The new system includes the rejection of divisions between the high and popular or mass art — instead of being observed from a distance, in galleries, museums, or other dedicated public spaces, art is given to the public in forms of leaflets and coupons or involves active participation of the public in the creation and use of art. The actions such as Sadness (1992/1993) or Coupons (1995) happened in markets and streets where the artist duo gave out small-format works to passers-by. Created with modest materials such as cardboard, rope, and paper, these works contained verses and texts that provoked thinking about the current situation in the country and its social implications. Coupons for sadness, love, fear, Sadness of Potential Genealogy, and Sadness of Potential Friendship are some of the works given away, creating an affective community of shared experience that would define Škart’s work over coming years. “All these separated countries, divisions of nationality and ethnicity, are very retrograde … We wanted to form an open, unframed form of collaboration; for resistance requires diversity,” stated Protić in one of his interviews. [70] By sharing their work freely, the artists addressed the issue of social decay, devaluation, and retrograde narratives that framed society in Serbia and much of the Yugoslav region during the war years, as well as the devastating social consequences of such politics. They also problematized the idea that art is to be praised only in spaces prescribed by an art institution.

The group democratized art and made it available and accessible to the widest audiences; the premise that art should be, and is technically perfect was also questioned and abandoned, together with the idea of the artist as an author. Instead, mistakes were accepted as an integral part of art, shifting the consideration of its value beyond aesthetic judgment. Other aspects, such as social engagement, solidarity, and empathic action, gained in primacy, and have been further explored in the group’s later works, such as Embroideries, Horkeškart (a combination of ‘choir’ and the name Škart in Serbian), the installation at the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale, and Poetree (Pesničenje). Housewives, students, and the general public actively participated in a creative process with Škart group. Art thus takes the form of creative action and becomes the property of everyone who participates in it. By including people from various backgrounds in the process of art production, Škart substitutes the idea of the artist as author with that of the artist as communicator; art is not an individual creative expression but a collective action — a format that proliferates in times of crisis. [71]

While eclectic in the choice of art forms and materials, Škart’s poetics also combines various concepts such as “waste, humour, and individual freedom”. [72] This freedom is likewise reflected in the group’s lack of interest in belonging to any institution of art. [73] Instead, the artist duo have engaged broader communities in the artmaking process, and through their works and art actions tried to build a space of alternative existence, values, and understanding. The creation of alternative spaces has been theoretically framed as social production of space, an idea that has been further developed but also criticized over the years. Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space, later accepted by many theorists including art theorists, contributed to the framings of collective art actions. [74] Art thereby becomes a conveyor of meaning beyond the established frames and creates a space for social interaction beyond the formal norms and ideas, often through affirmative social actions as an integral part of an artwork. Škart’s projects could be seen in this light — as a collective action that overcomes divisions and particular interests, and as a specific “architecture of the human relationships”, in Škart’s own words. [75]

Following similar aspirations, Homuseum happened in 2012 from the 28th March to the 9th April. During this period, a group of around thirty participants lived in the gallery space of Legacy-Gallery Zorić Čolaković. In a time when the two major museums in Belgrade — the National Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art — were not functioning due to reconstruction work, Škart group organized a performative action of living and creating inside an art institution. The action included various engagements, from participation at a conference (the action itself was part of a conference on graphic design in Belgrade), to workshops, debates, concerts, and other forms of creative expressions.

The idea, as formulated by Škart group, was to rethink the use of public infrastructure and institutions in times of their passive existence, with no public events or exhibitions happening at the time. The questions of who owns the institutions as a public good, and how they can be reused for creative actions outside of the formal institutional framework, were raised during the action. [76] Instead of waiting for a formal invitation, artists and activists entered the space and turned it into a creative hub, demonstrating that creative action cannot be contained within structural and infrastructural norms. As a home and a museum, the action blurred the lines between artistic and everyday practice, as the artists exhibited at home/museum, and lived in a museum/home. The relationships created between the participants and the institution showed the interconnectedness of the two, and highlighted the art/social action as a model pointing towards the democratization of art institutions.

Musealization of Alternative

The museums presented here are the repository of alternative histories, visual stories, and actions, in contrast to, and created against the practices propagated by the official institutions. Ideated and created on the margins of the dominant cultural course of the time, these projects provide a mirror to the post-socialist restructuring of memory and the visual symbols linked to it. Some of the museums are created as an encompassing concept around artistic practice, such as the Metaphysical Museum. Others are museums of activist engagement, musealized as the activism was happening. Again, the semantic decision infuses the artistic one, creating a museum on the level of language, but also in a concrete space of artistic action. Some of the museums compile objects, photos, and other memorabilia pertinent to the Yugoslav past, and combine them in unexpected ways, transforming ready-made objects into artistic forms. Such objects become the main artefacts of the museums created by artists. They contrast the cultural politics of the time and provide alternative spaces for artistic investigations of forbidden, neglected, or marginalized topics. They are a response by artists to the systemic misuse of culture and cultural institutions in everyday politics and nationalist rhetoric, and the politics of forgetting which was then dominating public discourse.

The Rabbit Museum, Yugomuseum, and the Inner Museum often combine artistic creativity with found objects, re-purposing them or just displaying them in new, and unusual combinations. The urge to collect among artists is not new, and has been present over different times and meridians. One such example is a work by Edson Chagas. He uses found objects in his Found Not Taken project (started in 2008 and ongoing), and creates new narratives by relocating and photographing them in different public situations than those in which they were found. [77] His work emphasizes both personal and collective issues; the urban environment discards and abandons objects and the artist brings the focus back to them, criticizing the economy of mass waste production but also obliteration and marginalization of all kinds. At the same time, he addresses his position as a migrant, first in London and later in Newport, Wales, where he is similarly marginalized and displaced from a familiar context. [78] The examined artists’ museums also reference both personal and collective issues in looking at discarded objects and memories, and find a new location for them inside unofficial museums. These spaces, created aside from any institutional framework, are repositories of not just a past that has been discarded and abandoned, but also of private recollections and examinations. The stories artists create reflect both the collective experience of being in-between two systems, those of socialism and liberal capitalism, and between versions of history. They also reflect the artists’ position as critical observers and internal migrants, who relocate their work from official institutions to private museums.

However, these museums are unique as their material is a combination of found and personal objects, and the artistic intervention is based on either combination of these elements or on the very process of naming. The political in these museums is located both in the artefacts and their location, but also in language. Museums that escaped an official stamp and which exist often only in the artists’ private places or temporarily in galleries and other exhibition spaces, communicate alternative history that is sidelined in order for a new, nationalistic narrative to take the central stage. Being named “museums” through the artists’ decisions, these projects disrupt hierarchies of cultural institutions. By showing that different types of museum can exist outside of the institutional circuit and can be created through personal initiatives, they add to alternative practices by widening the scope of their engagement. Going beyond individual artworks, they engage a wider cultural field and establish different points for the examination of memories and histories.

Artists name their practice, decide which artefact to include, and institutionalize their work in frames reminiscent of traditional institutions but also different from them. The gap between the two positions is a site of activism, critique, and political potential. Being a museum and at the same time not being, having the power to name it a museum, and still be on the margins of cultural events — and even sometimes being included and represented within an official institution — presents the complex position these museums have in relation to art institutions. In his analysis of social and political activism in the Balkans, political and cultural theorist and author Igor Štiks asserts that the examined forms of activist aesthetics could provide “a strong taste of emancipation” for those who participate in them, and challenge the scope of “what can be said, seen, heard and, finally, done”. [79] Similarly, the museums analysed here create a different framework for engaging with institutions and the past, which can provide an emancipatory framework for the future.

The museums are spaces of exiled artefacts and memory which gain agency through institutionalization. By showing that an understanding of the past, and one’s place in it, can still be thought from an alternative position, which can transform itself into an agent through personal decision, and that, following this line of thinking, a personal decision is still one of importance and can create new institutions, these museums present a site of hope. The practices involved did not seek to engage wider communities — in the context of Homuseum, the action only included a limited group of participants — but worked from the domain of individual reflections that invited participation. The illusory nature of authority and sanctioned histories is exposed, and a possible means of how to usurp and resist it is shown. Institutionalization did not overwrite the political potential of these projects. Instead, individual visions and artistic choices gain collective importance through a familiar institutional framework, with shared experiences and memories forging a new site of resistance.

Conclusion

The list of museums created by artists presented in this article is not exhaustive in any sense. While the focus was on the several museums created during the 1990s and early 2000s, there are other examples from this and earlier periods that formed museum-like repositories which could be included for consideration when discussing artistic reflections on sanctioned histories, stories, national ideas, and personal reflections during the Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav eras. These museums expanded on the topics of Yugoslav symbolic heritage, memory politics, art history, and the role of institutions, as is the case with Tadej Pogačar’s P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum, Anti-Museum by Vladimir Dodig Trokut, Kunsthistorisches Mausoleum by Goran Đorđević, and the Museum of Childhood by Vladimir and Milica Perić. There are also artistic projects that reference the institution of the museum in regional art practices, with one of the most well-known examples being Lia Perjovschi’s Knowledge Museum. However, the timeframe for investigation and the limits imposed by the current situation of world pandemic influenced the choices and strategies guiding this article.

The aesthetics of museums addressed here verges on surplus; a surplus of memories, of stories, and politics; a surplus that cannot be contained within the discourse of the everyday and politics as performed by the official institutions and individuals. The residues of the past and present intertwine, mingle, and react, creating a specific world of personal phantasmagorias intersected with public symbols. Some of the museums worked as museums; they had an exhibition space, working hours, and guided tours. Others were created in the domain of language, imagination, and performance, without a fixed space or any other elements of an institution. However, the appropriation of the term museum for these projects creatively positions them in dialogue with the meanings of a museum, its function as a repository of artefacts, and an active participant in the creation of national narratives and culture. These museums investigate and criticize through creative acts; they disclose stories and ideas; show what was erased or forgotten, and engage with the realities we live in. They also serve as private reflections on identity and artistic practice.

It is important, regarding the contemporary moment with its increased calls for the democratization and decolonization of knowledge and higher education, of institutions, and other domains responsible for creation of collective narratives and mythologies, to look back at these museums as individual responses to restrictions of all kinds, political and cultural oppression, and conflicts. They contribute to the plurality of practices, ideas, and positions, but also stand for exemplary forms of artistic action against limiting institutional possibilities. They deploy institutional and artistic elements which prevent their reading as pure artworks, art institutions, or performances. They do not belong fully to either of these categories, so to understand them it is necessary to go beyond the established definitions, and to look for the spaces of their interaction, as sites of political potential.

Nor should the ethical aspect of these museums be missed. In times of turmoil and the devaluation of institutions, artists took it on themselves to show the democratic potential and critical capacity the institution of a museum can have, if it dares to. The past cannot be erased, and it will resurface one way or another, perhaps in the forms of complex sculptural works or surreal combinations of found objects. It will remain present, even if only in art. Combining individual and collective experience, the museums took over the role official museums could not bear, due to political pressures and compromised institutional freedom. Irony, parody, cynical reflection on national myths, activism, and other forms of critical engagement mark these museums. Being museums but also artworks, they broaden the scope of understanding of creative limits and institutional borders, leaving neither undisturbed.

Literature

– Anđelković B., Dimitrijević B. Poslednja decenija: umetnost, društvo, trauma i normalnost // Anđelković B., Dimitrijević B., Sretenović D. (eds.) O normalnosti: umetnost u Srbiji 1989–2001. Belgrade: Publikum, 2005. P. 9–130.

– Bajić M. Yugomuseum: Memory, Nostalgia, Irony // Borić D. (ed.) Archaeology and Memory. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2010. P. 195–203.

– Bajić M. Backup. Belgrade: Cicero, 2006.

– Birač D. Politička ekonomija hrvatske: obnova kapitalizma kao “pretvorba” i “privatizacija” // Politička misao, № 57 (3), 2020. P. 63–98.

– Bogdanović A. Mrđan Bajić: Skulptotektura. Belgrade: Fondacija Vujić kolekcija, 2013.

– Božović Z. Škart // Božović Z. (ed.) Likovna umetnost u Srbiji ‘80-tih i ‘90-tih u Beogradu. Belgrade: Remont — Independent Art Association 2001. P. 76–85.

– Bračić N. The Metaphysical Museum // Placard from the exhibition Upside-Down: Hosting the Critique (Belgrade City Museum, 2016).

– Bugarinović N. Vajar Mrđan Bajić na Bijenalu u Veneciji // Radio Slobodna Evropa, 2007, https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/704685.html.

– Ćirić M. Podsetnik Na Istoriju Institucionalne Kritike U Srbiji (Verzija Druga) // DeMaterijalizacija Umetnosti, http://dematerijalizacijaumetnosti.com/podsetnik-na-istoriju-institucionalne-kritike-u-srbiji/.

– Cumming L. Damien Hirst: Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable Review — Beautiful and Monstrous // The Guardian, April 16, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/apr/16/damien-hirst-treasures-from-the-wreck-of-the-unbelievable-review-venice.

– Dedić N. Jugoslavija u post-jugoslovenskim umetničkim praksama // Sarajevske sveske, № 51, 2017.

– Dimitrijević B. Koraci i raskoraci: kratak pregled institucionalne koncepcije i izlagačke delatnosti Muzeja savremene umetnosti 2001–2007 // Sretenović D. (ed.) Prilozi za istoriju Muzeja savremene umetnosti. Belgrade: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2016. P. 315–346.

– Dragićević Šešić M. Counter-Monument: Artivism against Official Memory Practices // Култура/Culture, № 6 (13), 2016. P. 7–19.

– Dragićević Šešić M. Umetnost i kultura otpora. Belgrade: Clio, 2018.

– Dražić S. U kom grmu leži zec? // Grginčević V. (ed.) Džafo. Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina, 2011. P. 141–149.

– Džafo N. The Rabbit Who Ate a Museum // Placard from the exhibition Upside-Down: Hosting the Critique (Belgrade City Museum, 2016).

– Enwezor O. The Production of Social Space as Artwork: Protocols of Community in the Work of Le Groupe Amos and Huit Facettes // Stimson B., Sholette G. (eds.) Collectivism after Modernism, the Art of Social Imagination after 1945. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. P. 223–251.

– Fraser A. From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique // Artforum, № 44 (1), 2005. P. 100–106.

– Galliera I. Socially Engaged Art after Socialism: Art and Civil Society in Central and Eastern Europe. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2017.

– Ganglbauer G. Artifacts of Unknown Usage // Gangan Lit-Mag (blog), December 2005, https://www.gangan.at/36/nenad-bracic/.

– Gregorič A. Interdependence // Glossary of Common Knowledge, https://glossary.mg-lj.si/referentialfields/historicisation/interdependence.

– Gregorič A, Milevska S. Critical Art Practices That Challenge the Art System and Its Institutions // Gregorič A., Milevska S. (eds.) Inside Out. Critical Discourses Concerning Institutions. Ljubljana: Mestna galerija Ljubljana, Muzej in galerije mesta Ljubljane, 2017. P. 8–34.

– Jovanović S. Umetnički kolektiv grupa ‘Škart’ // Jovanović S. (ed.) Škart: poluvreme. Belgrade: Museum of Applied Arts, 2012. P. 12–19.

– Lazar А. The Inner Museum // Placard from the exhibition Upside-Down: Hosting the Critique (Belgrade City Museum, 2016).

– Lazar A. Od Oblika K Zaboravu: Akumulirana Praznina Unutrašnjeg Muzeja Dragana Papića // Život umjetnosti: Časopis za suvremena likovna zbivanja, № 95 (2), 2014. P. 126–131.

– Lefebvre H. The Production of Space. Wiley, 1992.

– Malevich K. From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism [1915] // Bowlt J.E. (ed.) Russian Art of the Avant Garde: Theory and Criticism 1902–1934. New York: The Viking Press, 1976. P. 116–135.

– Marstine J. Introduction // Marstine J. (ed.) New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Malden, Oxford, Carlton: Blackwell Publishing, 2008. P. 1–37.

– Matović D.B. Balkanizacijom U Svet // Novosti, October 11, 2003, https://www.novosti.rs/vesti/kultura.71.html:151011-Balkanizacijom-u-svet.

– Merenik L. Mrđan Bajić, ili godine insomnije // Veličković V. et al. (eds.) Mrdjan Bajić : Reset : Srpski paviljon = Padiglione Serbo = Serbian Pavilion. Belgrade: Cicero, 2007. P. 24–37.

– Mmb Metaphysical Museum Beograd // October 25, 2013, http://hasselbaker.blogspot.com/2013/10/mmb.html.

– Oliveira A.B. The Ethics, Politics, and Aesthetics of Migration in Contemporary Art from Angola and Its Diaspora // African Arts, № 53 (3), 2020. P. 8–15.

– Pantić R. Jugoslavija v mednarodni delitvi dela: od periferije k socializmu in nazaj k periferiji // Borec: revija za zgodovino, antropologijo in književnost, № 73, 2021. P. 787–789.

– Papić Ž. Europe after 1989: Ethnic Wars, the Fascisation of Social Life and Body Politics in Serbia // Filozofski vestnik, № 23 (2), 2002. P. 191–204.

– Piotrowski P. Kritički Muzej. Kruševac: Sigraf, 2013.

– Purić B. In Praise of Deserters // Journal of Curatorial Studies, № 3 (2+3), 2014. P. 388–390.

– Radisavljević D. Od individualnog u kolektivno i nazad // Grginčević V. (ed.) Džafo. Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina, 2011. P. 7–42.

– Samary C. The Social Stakes of the Great Capitalist Transformation in the East // Debatte, № 17 (1), 2009. P. 5–39.

– Škart // http://www.skart.rs/.

– Štiks I. Activist Aesthetics in the Post-Socialist Balkans // Third Text, № 24 (4–5), 2020. P. 461–479.

– Stokić J. Pejzaž Mrđanna Bajića (ili: kako prevazići provincijalizam malih nacija) // Veličković V. et al. (eds.) Mrdjan Bajić : Reset : Srpski paviljon = Padiglione Serbo = Serbian Pavilion. Belgrade: Cicero, 2007. P. 38–49.

– Szreder K. Productive Withdrawals: Art Strikes, Art Worlds, and Art as a Practice of Freedom // e-flux Journal, № 87, 2017, https://www.eflux.com/journal/87/168899/productive-withdrawals-artstrikes-art-worlds-and-art-as-a-practice-of-freedom/.

– Timotijević S. Muzej u senci / Shadow Museum // Art magazin, October 14, 2008, http://www.artmagazin.info/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=808&Itemid=35.

– Vukadinović D. Nenad Bračić — Kremzarski nalaz, izgubljeni svetovi 4001 p.n.e. // Moment: časopis za vizuelne medije, № 19, 1990. P. 81–88.

– Yildiz S. The Evolution of Škart, the Serbian Art Collective Forging Communities through War and Peace // Calvert Journal, July 7, 2020, https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/11936/skart-artcollective-serbia-community-war-and-peace.

– Izbacivanje Radova Dragana Papića // Marka Žvaka video, 4:43, 2007, https://markazvaka.net/izbacivanje-radova-draganapapica/.

– Unutrašnji muzej Dragana Papića // Marka Žvaka video, 6:00, 2007, https://markazvaka.net/unutrasnji-muzej-draganapapica/.