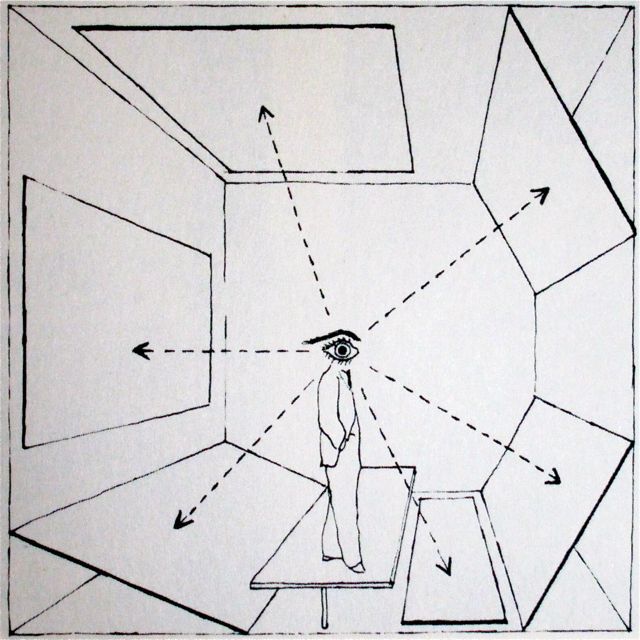

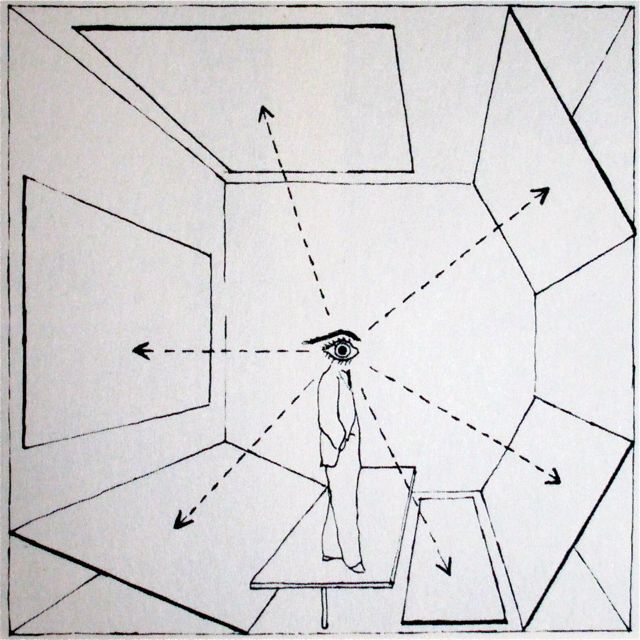

“Bauhaus” means literally “building house”, but architecture was not the chief discipline of the school, which we know by that name. What the Bauhaus developed was a metadiscipline around the principle of the “Gesamtkunstwerk” – a total, holistic approach to the creation of art and its perception as an organic part of the World. Herbert Bayer, a Bauhaus student (1921–1925) and teacher (1925–1928), framed a theory of the “extended field of vision”, which reflects this totality and sets new coordinates for the design of space in a museum exhibition. The scheme, by which he proposes to be guided in such design, [1] depicts a person surrounded by expositional surfaces located in different planes.

The viewer, placed at the centre of the space constructed by the artist, has the ambition to capture an immense “extended” field of 360°, and is thus a new version of the Renaissance man who tests potentially limitless possibilities. On the one hand, such an exhibition system serves as an auxiliary mechanism, activating the gaze, provoking its movement, widening the angle of vision, sometimes raising the level of the eyes beyond what is natural.[2] On the other hand, Bayer writes of “improved” human vision, evoking the idea of special powers and resonating not only with the Renaissance idea of the physically perfect polymath, but also with the early 20th-century idea of the Superman/Übermensch.

***

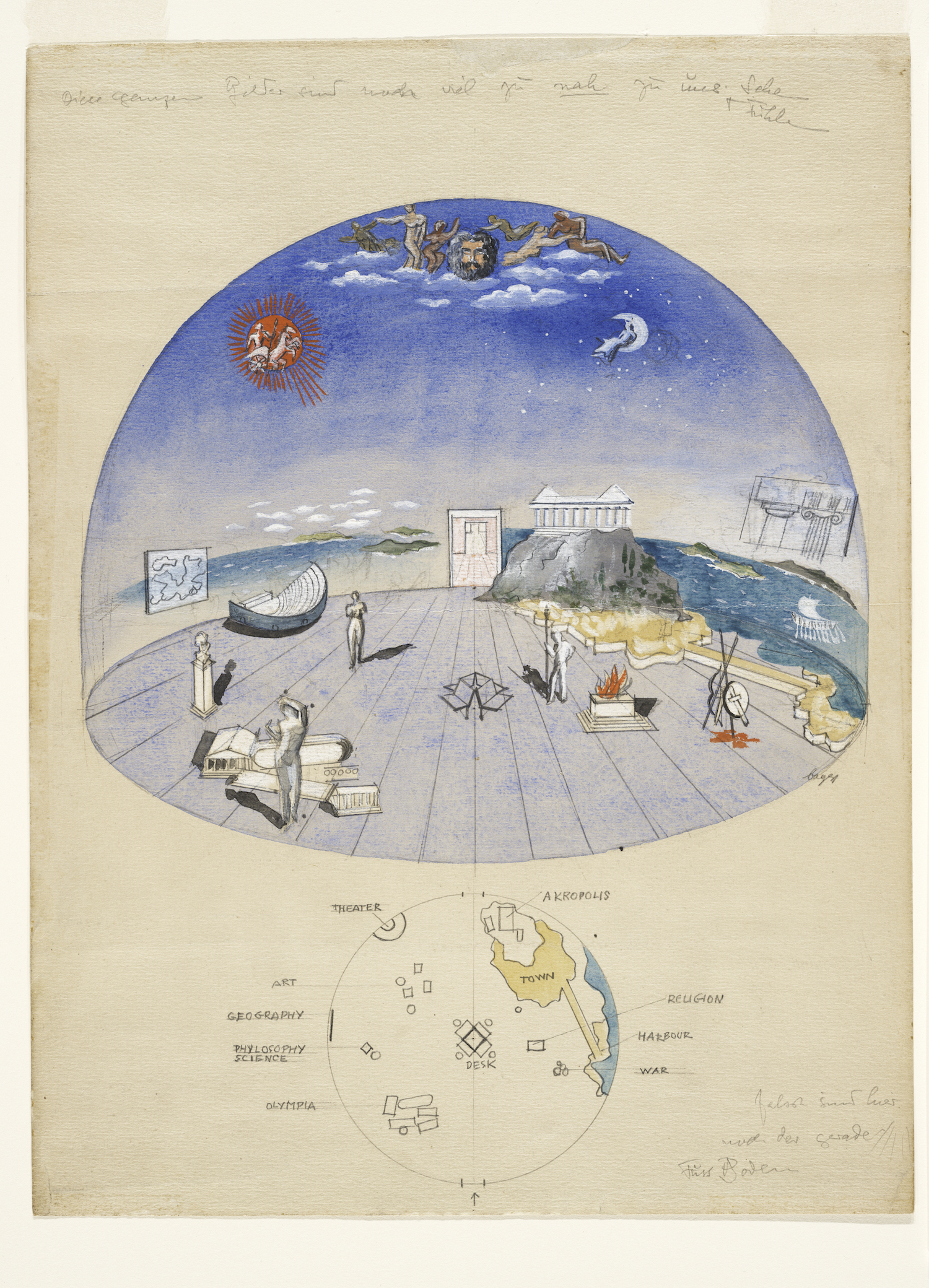

The social aspect of the Bauhaus construction is obvious, but its multidirectional time vectors, characteristic particularly of Bayer, which led to the idea of a “new man”, should also interest us. [3] The first vector travels into the past, to the Renaissance and beyond, to antiquity. Despite the strong biocentric tendencies of the Bauhaus, “man as the measure of all things” was a key principle of the school, as seen in texts by Oskar Schlemmer, where he quotes Protagoras. [4] Schlemmer was the author of the Bauhaus course “Der Mensch” (“The Human Being”) and the architect Hans Fischli recalls how Schlemmer made students look at ancient sculpture, taught them ancient Greek philosophy and expounded the principles of harmony on the example of human anatomy. [5] Laszlo Moholy-Nagy refers to the figure of Leonardo da Vinci who with his “gigantic plans and achievements” is “a great example of the integration of art, science and technology”. [6] Reminiscences of antiquity have special power for Herbert Bayer. This can be seen in the antique imagery that runs through his paintings, photomontage and graphic art, but also in his unconditional reliance on geometry, which for him was synonymous with clarity [7] and could therefore open the way to universals. This constructive principle, which was the foundation of his practice, is akin to the architectural principles of the era of humanism, described by Rudolf Wittkover – a mathematical interpretation of the world and an unshakeable belief in the mathematical community of macro- and microcosm, which is the legacy of the ancient Greeks. [8] Also in Bayer’s work we find a longing for the Greeks’ universalism, for their ability to form a comprehensive picture of the world and a wholeness of feeling. Bayer’s sketches for museum installations, made in 1947, show self-sufficient universal spaces, where there is place for acropolis, altar, amphitheatre, ancient sculpture and other elements defining Greek civilisation, ordered by a superimposed perspective grid. Bayer attaches a note to one of these sketches: “All these images are still much too close [emphasised] to us. See / + Feel.” [9] Not being intended for any specific exhibition, these sketches can be seen as a crystallisation of Bayer’s ideas about the space of a museum exhibition in general. They appear to have been made during a visit to Colorado (where Bayer lived) by Alexander Dorner, who was then working on the book The Way Beyond “Art “: The Work of Herbert Bayer (1947), and they remained in Dorner’s archive together with the notes. [10]

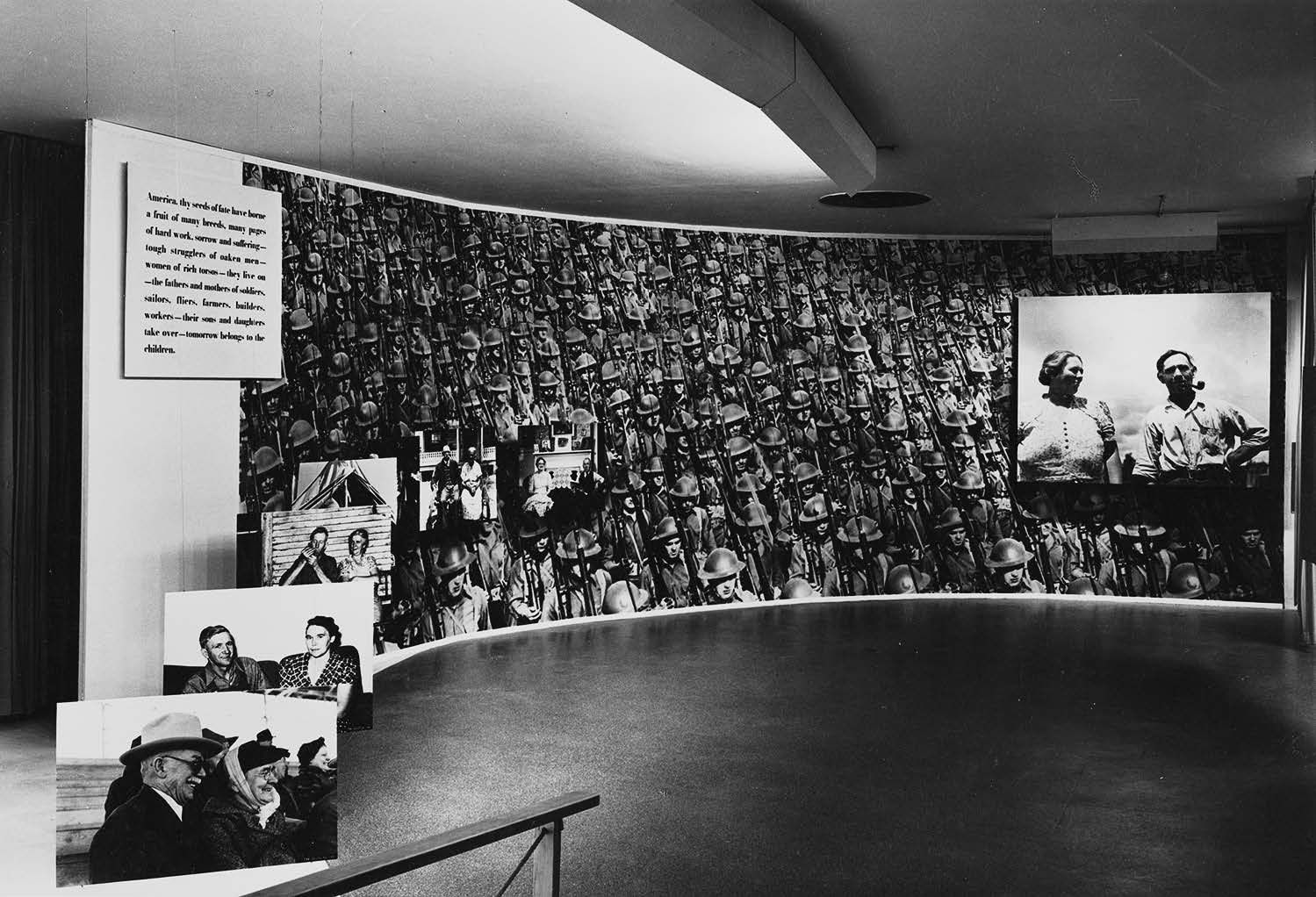

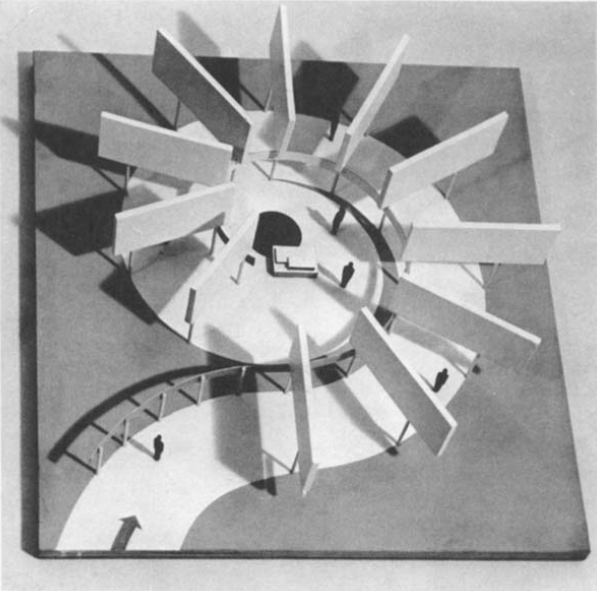

Bayer gives the viewer a place exactly in the middle, unfolding a panorama before the viewer’s gaze. He finds the spherical form to be most appropriate: his “extended field of vision” evolves from the 1930 version, where the panels roll over the viewer like a wave, to the version of 1935, where the viewer is at the centre. In the 1942 MoMA exhibition, Road to Victory, Bayer constructed a hemisphere of photographic panels in the entrance zone, dispensing with walls. [11] A year later, in the sequel exhibition Airways to Peace, Bayer installed a huge globe, which the viewer could go inside and see “how Europe, Asia and North America are clustered about the North Pole.” [12] This globe and the dome over an antique museum landscape in the 1947 sketch by Bayer echo one another.

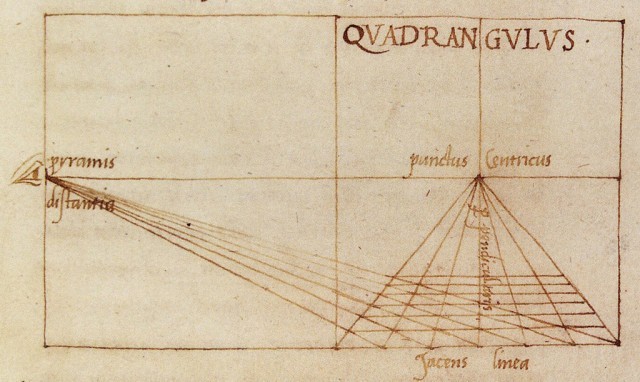

For both Bayer and Dorner the central positioning of the viewer and the preference for spheres are steps towards the Gesamtkunstwerk. But for Dorner, the Gesamtkunstwerk as a concept remains within romantic limits: in his view, it was romanticism that gave rise to a new type of space, provided a plurality of viewpoints, introduced a fourth dimension – that of time – into art, and allowed the artist to move away from the limited Renaissance perspective towards what he called “super-perspective”. [13] For Bayer, by contrast, the romantic concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk is no more than a bridge to the ancient source, which remains of paramount importance. Bayer’s “extended field of vision” takes up the visual code of Renaissance researchers into perspective: the rays of vision and the single eye from which they emanate. The eye is, in essence, isolated from the rest of the body and is more of a symbol – precisely what it was for Leon Battista Alberti. Vision for Bayer is an indispensable and key tool, and this sets him apart from other theorists of art, including Dorner, for whom the optical and haptic methods of perception are unstable and always culturally determined. However, the monocularity of his scheme, which Bayer carries into the future as part of an ideal, antique “core”, becomes a checkpoint, a mark of that which, in Bayer’s theory, is in fact anachronism and a nostalgic remnant that runs counter to his practice.

***

According to Jonathan Crary, monocularity, together with perspective and geometric optics, was the basis of the Renaissance vision, where the world was constructed on the basis of constants that had been brought into the system, while all contradictions and irregularities were eliminated. [14] This world is primarily static, while the chief mark of the new world, which the Bauhaus glimpsed, was dynamism. Theses about this new world and new vision are contained in the texts of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, New Vision (1932) and Vision in Motion (1947): “The renaissance constructed the scene to be painted from an unchangeable, fixed point following the rules of the vanishing point perspective. But speeding on the roads and circling in the skies has given modern man the opportunity to see more than his renaissance predecessor. The man at the wheel sees persons and objects in quick succession, in permanent motion.” [15] Precisely this perception, Moholy-Nagy believes, is what enables simultaneous comprehension of the world. It is a creative act where a person sees, thinks and feels, not a sequence of phenomena, but the world as an integrated, coordinated whole, [16] an act that bridges the divide between the ancient Greeks and us, a divide that was formulated by Matthew Arnold: “They regarded the whole; we regard the parts.” [17]

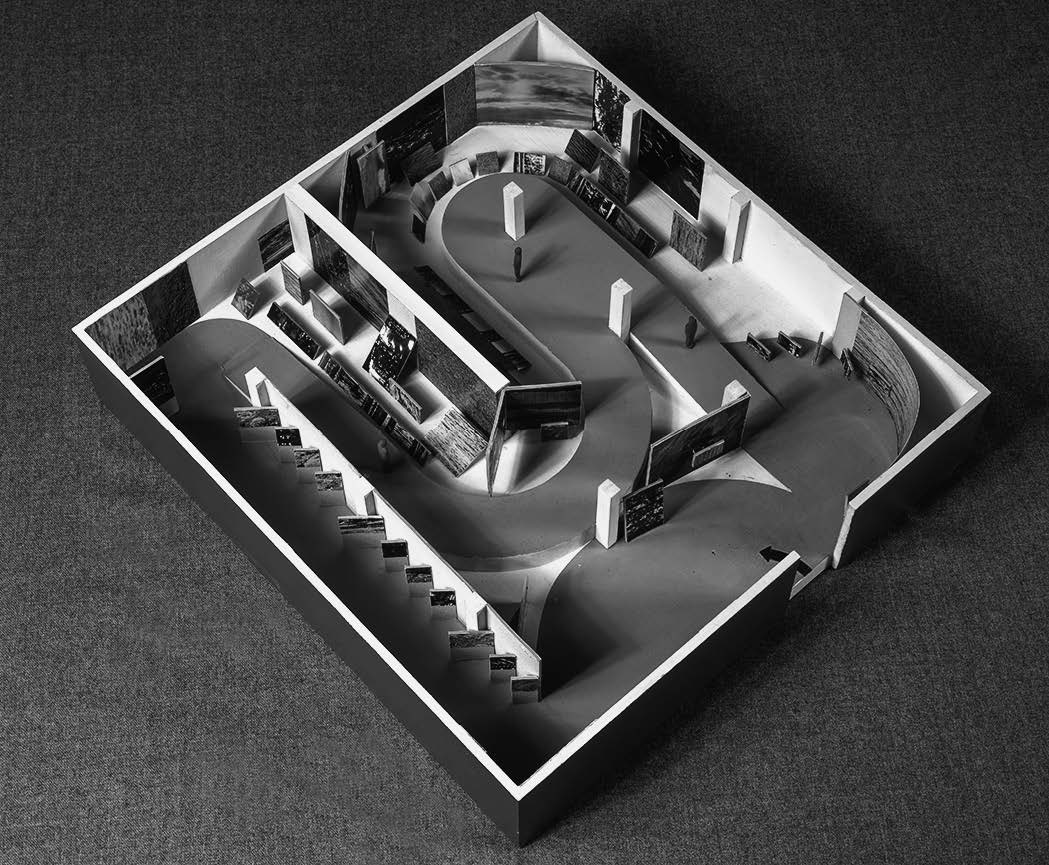

bayer strives to achieve the most complete optical perception of objects by the use of expositional techniques, but this goal becomes secondary when the objects – like signs – are revealed only within the framework of a general system.

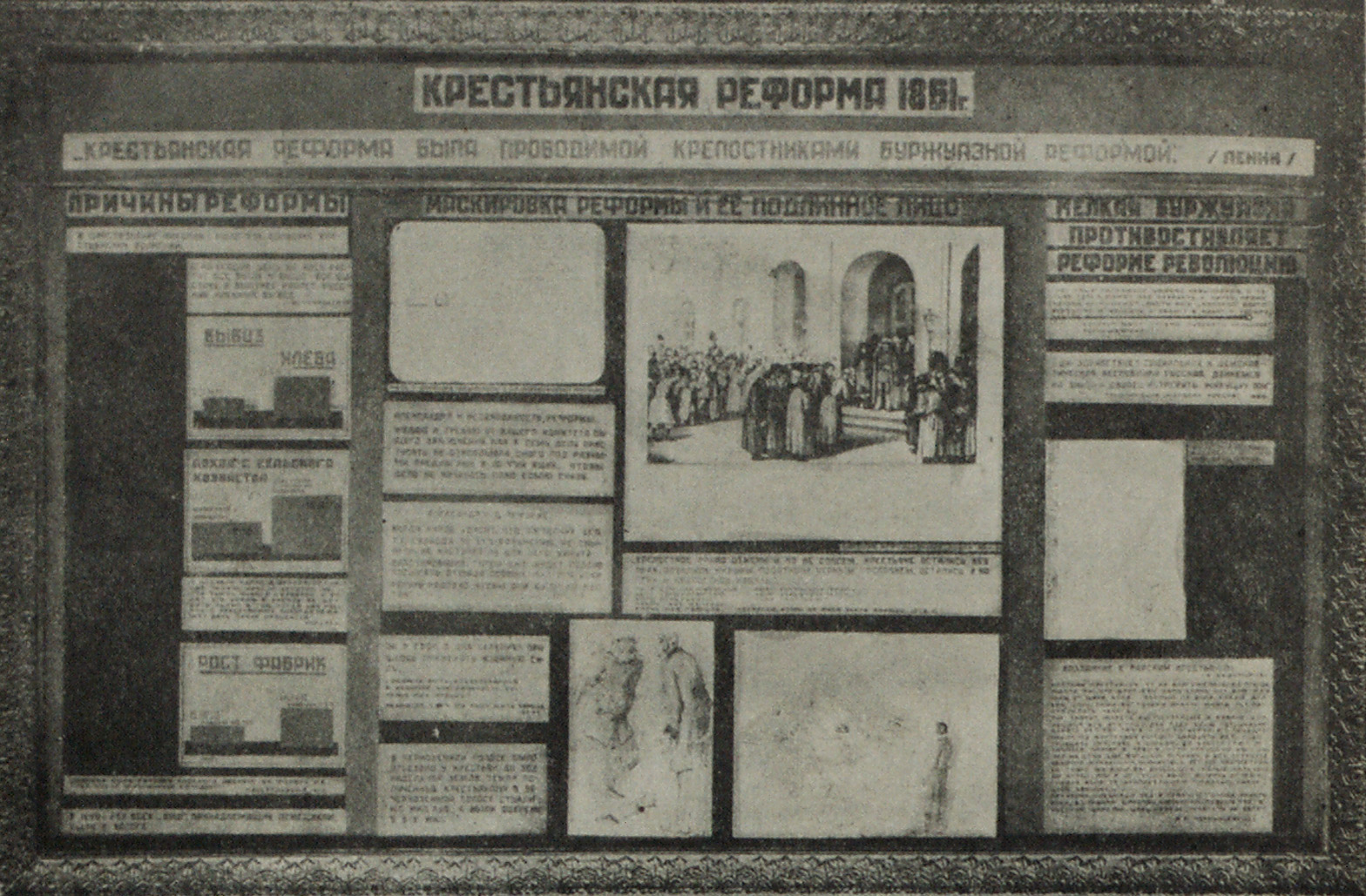

The principles of the “new vision” were materialised at the so-called Werkbund exhibition (the German section of a decorative arts salon held at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1930). The display was designed by Herbert Bayer together with Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, so that it was essentially a Bauhaus exhibition, or at least a forerunner of the landmark exhibition of the school, which took place in 1938 at MoMA in New York. [18] The printed materials for the Werkbund exhibition, prepared by Bayer, describe a first version of the “scheme for an extended field of vision”.

The scheme was implemented with complications and intensifications from that exhibition onwards. Bayer’s devices, in addition to the dynamic arrangement of photographic panels at different levels and at different angles, included the use of ramps, giving the viewer a choice of viewpoint, and the scaling of photographs and montages, in which Bayer acknowledged the influence of El Lissitzky and his Soviet pavilion at the Pressa exhibition in Cologne (1928). [19] Bayer also worked to deconstruct the pictorial plane even further, as at the exhibition of the Construction Workers’ Trade Union in Berlin in 1931, where a series of vertical uprights bearing photographs on their left, right and in the intervals in between, presented the viewer with three different scenes, which he/she saw one after another when moving past the slats.

The world that Bayer tries to build with architectural and visual means is radically different from what is represented through the visual pyramid. Assembled from many unreconciled pictures from different viewpoints, it is marked by uncertainty and instability, which, in the words of Ernst Gombrich, “is likely to arouse not only scepticism, but even resistance. […] For it must be granted that our aim will always be to see a stable world, since we know the physical world to be stable. Where this stability fails us, as in an earthquake, we may easily panic.” [20] Gombrich refers to a world characterised by such instability as “slightly elastic at the edges.” [21]

20th-century man had the benefit of a hybrid visual apparatus, acquiring new capabilities and new, non-renaissance perspectives thanks to the advent of photography and film. Photography was the most important and advanced art form for the Bauhaus and for Bayer, and from the end of the 1920s, the cine camera was more than a means of expression or reproduction – it was a tool of vision that freed the viewer from linear perspective and opened the high road to a mobile, multidirectional perception of space. [22] As Gyorgy Kepes wrote in his book The New Landscape in Art and Science, science and technology showed us “things that were previously too big or too small, too opaque or too fast for the unaided eye to see.” [23] Aerial photography brought a fundamental shift in the awareness and projection of space by making it possible to capture the curvature of the horizon, which traditional representation on the plane had ignored. Bayer pointed out the distortions that arose from this shortcoming in his commentary to Airways to Peace, which made use of hemispheres in order to “produce a true vision”. [24] According to him, many “strategic errors” were made in wartime as a result of “consulting distorted maps, instead of globes”. [25]

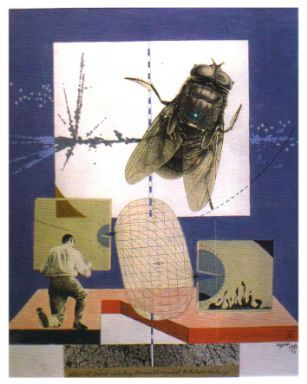

Bayer’s relationship with space is summed up in a short text that he wrote late in life, In Honor of Albrecht Dürer: an Interpretation of Adjusting the Vanishing Point”, [26] the title of which refers to his collage Albrecht Dürer Adjusting the Vanishing Point to Future History. Bayer explains that in this work he brings together conflicting, but mutually enriching approaches – the rational-constructive and the romantic-instinctive – whose rivalry is also evident in his own practice. The composition has the appearance of an allegory: Bayer does not offer direct interpretations, but says that the kneeling figure suggests analogies with the introduction of perspective and with Dürer, who might serve as a symbol of the new perception of space. So the special temporal logic of Bayer’s theory is emphasised once again. Curves and other features characteristic of his architecture are justified by the “new” vision and perception that was being discovered at the time. They are entirely consistent with what El Lissitzky, who also studied the geometry of space, called, in his essay A and Pangeometry, the destruction of immovable Euclidean space by Lobachevsky, Gauss and Riemann. Nevertheless, the Renaissance is affirmed by Bayer as a certain “return point”, imposing a loop that cannot be overcome.

***

A way of overcoming it can be glimpsed if, once again, we recognise a dehiscence between Bayer’s theory and practice and admit that the principles, by which he constructs space are not, in fact, based on optical perceptual experience and that that such experience only seems to be the determining factor. What operates instead is the experience of reading a map. Ernst Gombrich drew the distinction between these two types of representation in his essay Mirror and Map. The map does not give optical distortions, illusions and omissions, because reading the map, like reading letters from the page of a book, does not depend on the distortions of perspective, on the angle and viewpoint from which the map is seen. [27]

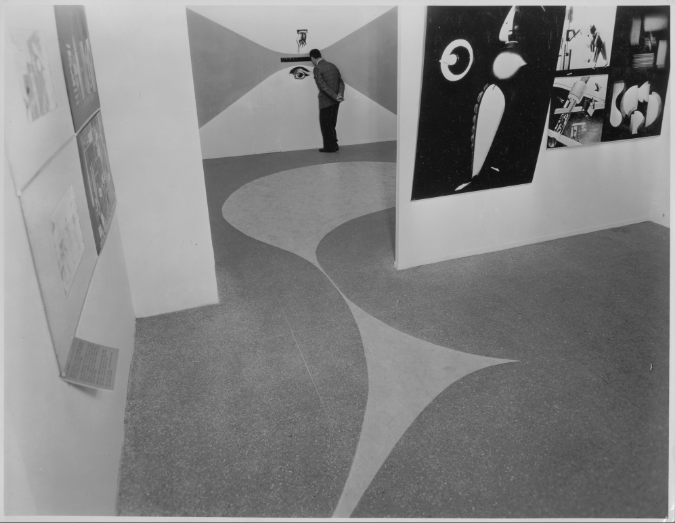

Bayer strives to achieve the most complete optical perception of objects by the use of expositional techniques, but this goal becomes secondary when the objects – like signs – are revealed only within the framework of a general system. Bayer sees the exhibition space as a sort of map; his concern from the outset is with issues of navigation and route. And while, in the German section at the Paris Grand Palais in 1930, Bayer’s solutions were largely subordinated to the old architecture of the building, at the New York exhibition of 1936 he proposed a genuinely innovative model of space. The exhibits were placed on giant panels under which the viewer had to pass in order to reach the centre. [28] In MoMA’s Bauhaus: 1919–1928 exhibition of 1938 Bayer used abstract decorative forms and other signpost elements to intimate the direction of movement through the exhibition.

In Road to Victory (subtitled “A procession of photographs of the nation at war”) and Airways to Peace, the path through the exhibition is thematically installed in the name. In the case of the first exhibition, the psychological culmination and turning point of the story – the attack on Pearl Harbor – coincides with the spatial culmination: the visitor ascends a ramp and, at the top, makes a 180 degree turn to see two photographs of the historic moment. [29]

This approach, however, can turn out to be – and in Bayer’s case often does turn out to be – a manipulation of the viewer, paradoxically at odds with the artist’s desire to endow that viewer with a new vision and new relationships with his/her environment.

Translation: Ben Hooson