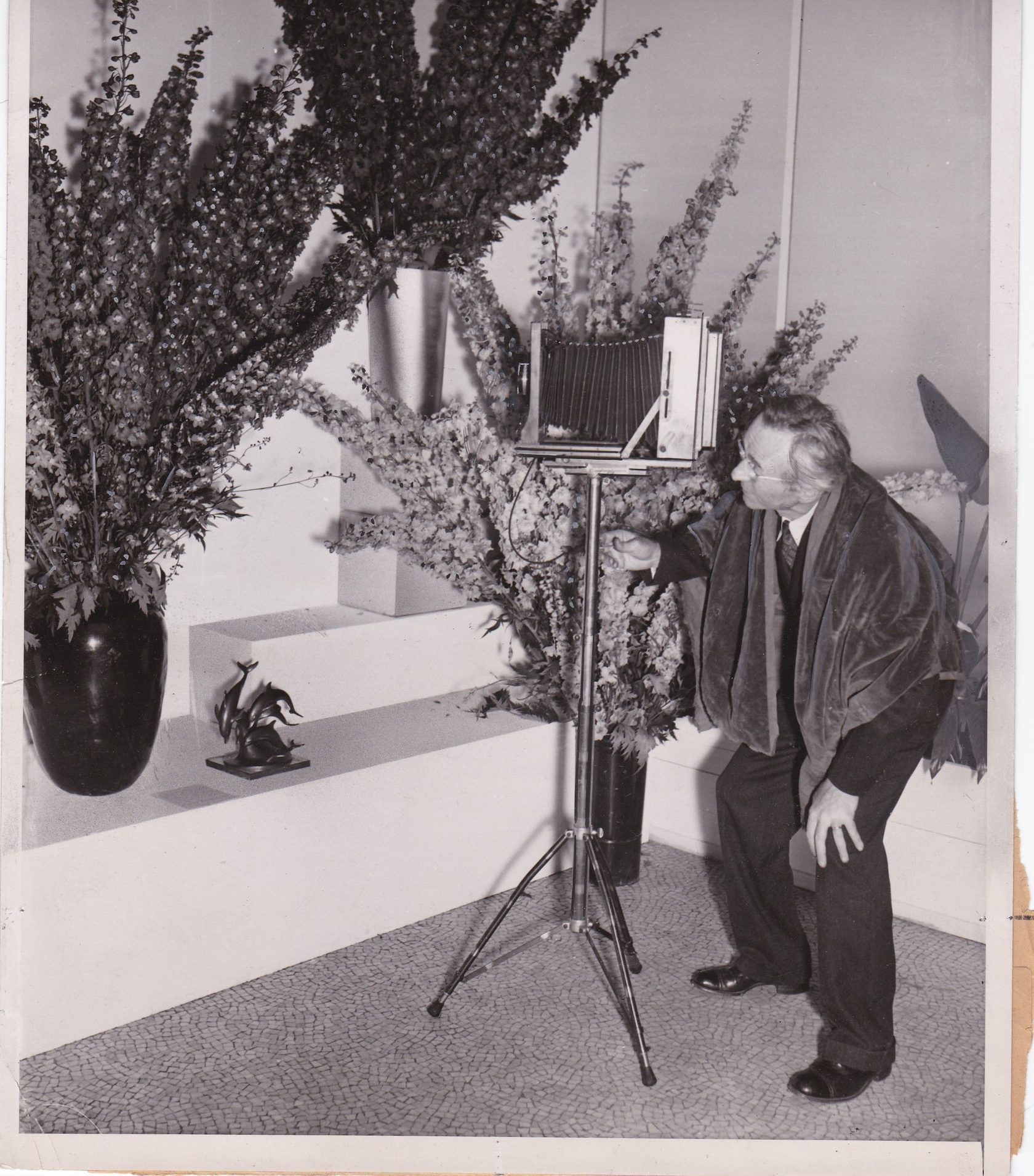

Alexander Dorner is acknowledged as the one of the most innovative curators of the pre-war era. Atmosphere rooms, a concept proposed by Dorner, were created by El Lissitzky in 1927 (Cabinet of Abstract, 1927) and designed but not realised by László Moholy-Nagy (Room of the Present, 1930) at the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover have been acclaimed as role models of the modernist museum. This book offers new insight into Dorner’s art philosophy, curatorial practice, his projects in the United States after his escape from Nazi Germany in 1937, as well as number of controversies surrounding his activities and legacy.

The first section is a collection of articles on Alexander Dorner’s activities at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design (RISD Museum), which he headed in 1938 — 1941. Dorner’s openness to an egalitarian educational curriculum and his concept of the museum as a powerhouse, discussed by Rebecca Uchill in Chapter 2 of the book, are concepts of much relevance for contemporary museums worldwide. Today Dorner’s impact on the RISD agenda is highlighted by the annual Dorner prize: “An award for a creative intervention in the museum’s spaces” (p. 108). The marriage between Dorner and RISD was, however, short-lived and unhappy. He omitted to mention his period as RISD director in his autobiographical preface to the catalogue The Way Beyond Art (1947) (p. 95), and RISD staff were not sad to see the back of this stranger with awkward food habits and a total disregard for the members of the local intelligentsia who served as RISD trustees (Chapter 1 by Andrew Martinez, pp. 26−31; Chapter 4 by Daniel Harkett, pp. 95−105). His cause was not helped by xenophobia in the American museum world and society on the eve of the Second World War, when 250 German art historians and museum directors had recently arrived in the USA from Nazi Germany (p. XV) and the broader refugee crisis had roused hostility to German nationals, the Jewish community, other aliens and anyone suspected of Communists sympathies.

In a thought-provoking account “Tea vs. Beer. Class, Ethnicity, and Alexander Dorner’s Troubled Tenure at the Rhode Island School of Design”, Daniel Harkett recounts the history of RISD before and after Dorner’s arrival. The picture he paints is of a highly conservative, Protestant and anglophone regional museum, closed to internationalism and multiculturalism, and utterly unprepared for the arrival of this radical foreigner, who was catapulted into RISD directorship under the personal protection of Alfred J. Barr, Walter Gropius and other prominent figures of the American art scene.

Soon after his arrival in the US, in the late 1930s and 1940s, Dorner collaborated with several key figures of American modernism, including Henry-Russell Hitchcock, with whom he worked on the Rhode Island Architecture Exhibition at RISD in 1938. Hitchcock was less than satisfied with the partnership, as explained in Chapter 3 by Dietrich Neumann “‘All the struggles of the Present’ Alexander Dorner, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, and Rhode Island Architecture”, although the American historian successfully continued a series of shows on modern American architecture that had been inspired by Dorner.

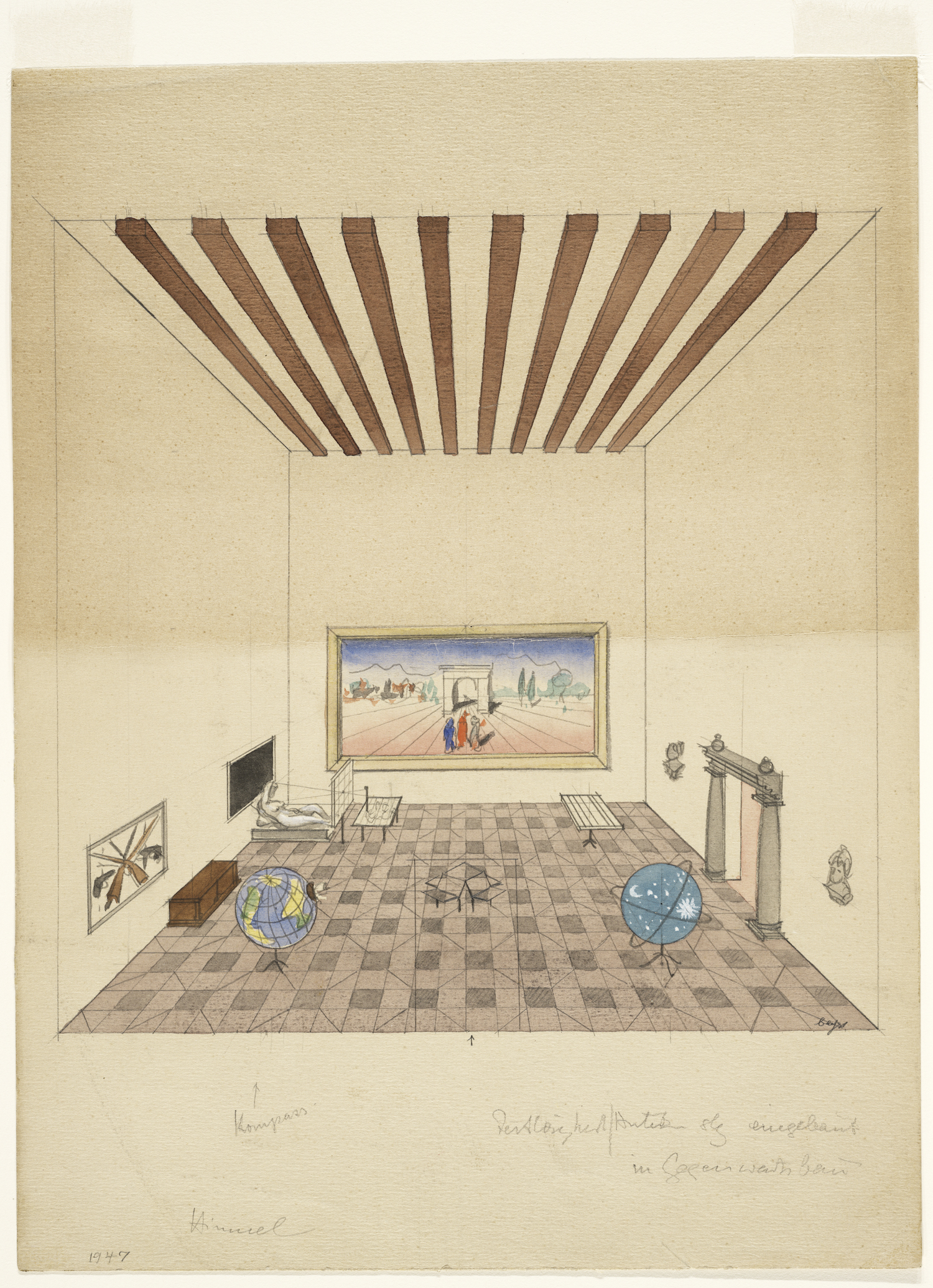

Dorner’s influence was also visible in Herbert Bayer’s design for the Airways to Peace show at MoMA in 1943 (p. 63). Dorner’s keen interest in the special arrangement of viewpoints and in four-dimensional effects dated back to his Hanover atmosphere rooms (the room created by El Lissitzky was destroyed by the Nazis in 1936, but reconstructed in 1969; the design by László Moholy-Nagy was never realized, but was reconstructed for LACMA in 2017). Bayer would produce sketches featuring multipoint spatiality soon after a short-lived collaboration with Dorner for the RISD retrospective of Bayer’s works, The Way Beyond Art, in 1947.)

the starting point for dorner is the regrettable detachment of museums from the needs of life.

The impact of Dorner’s art historical agenda is also visible in the all-time bestseller of modernist architecture, Siegfried Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture, though Dorner’s ideas are not attributed by Giedion (pp. 48−49).

As Blythe’s collection suggests, unwillingness to recognize the impact of Alexander Dorner’s thought and oeuvre on the modernist agenda in the USA may well have geopolitical reasons related to the conventions of the Cold War era. The analytical articles in the book reveal a contradictory attitude towards Dorner’s personality, activities and philosophy among museum staff at RISD in the early 1940s. Chapter 4 by Daniel Harkett discusses how Dorner was caught in a “double-bind”, as he was suspected of being both a Nazi and a Communist. His behavior was inscribed in the anti-Semitic paradigm of the era when he was judged to be a supporter of Jewish refugees (p. 105). Aside from problems of personality race and politics, Dorner’s artistic ideas may have compounded his chilly reception in America. As Sarah Ganz Blythe argues in the next chapter of the book, “The Way Beyond Museums”, Dorner’s concept of the evolution of art history, drawn from Hegel, led either to Hitler or to Marx (p. 118). That such nervousness can still be inspired by a commitment to Hegelianism shows that the Cold War legacy remains relevant to today’s museum expertise.

The second part of the book contains texts by Alexander Dorner written after his arrival in the USA. “My Experiences in the Hanover Museum (What Can Art Museums Do Today?)” from 1938 is followed by a 64-page unpublished manuscript from 1941 “Why have art museums?” The two texts provide a comprehensive insight into Dorner’s original concept of atmosphere rooms. Chapter 5, “The Way Beyond Museums” by Sarah Ganz Blythe, introduces these texts, providing historical and cultural background, which brings out their importance for European and US museological practice, particularly educational practice.

As Rebecca Uchill, a leading scholar of Dorner’s oeuvre in the English-speaking literature, has pointed out, contemporary scholarship, interested primarily in the innovative and abstract concepts of international modernism epitomized by the works of El Lissitzky and László Moholy-Nagy, has tended to disregard the coherent “architectural and interpretive framing apparatuses of Dorner’s curatorial container.” [1]

The starting point for Dorner is the regrettable detachment of museums from the needs of life. In the well-documented essays published in Why Art Museums? he outlines a line of thought that combines art history with museum display, describing the function of a museum with a collection of historical art and how such a collection should be displayed in modern surroundings. For Dorner, contemporary art has no need of explanation as it directly refers to contemporary life and ideas. His concern is with the art of the past, and he traces the emergence of historical styles, first in Winckelmann’s works on Greek style (p. 215), then in the context of the Gothic revival and in artistic spheres up to his own time. The problem, which Dorner identified, was that art museums perceived and taught appreciation of all these styles from an imagined perspective of “the eternal laws of beauty”, with total disregard for the temporal aspect (p. 215). This approach, he believed, had been cemented by Formalism, based on the autonomy of individual perception and empathy (Dorner calls this “Romanticism”, p. 152). He credits Aloïs Riegl as the first to overcome this idealist, timeless evolution of art history by attributing time-bound features to each epoch in his work Late Roman Art Industry (1901). This new, time-aware art historical approach had been further elaborated by Dorner’s classmate Erwin Panofsky, who analyzed perspective-related aspects of art historical development, as well as Aby Warburg with the Mnemosyne Atlas (1924 — 1929) and his search for “how specific motives emerged in ancient Greece and persisted through to Weimar Germany” (p. 118). Dorner valued these studies for their keen sense of temporal distance and the autonomy of each cultural epoch, which must be made visible and recognizable in a museum display.

But what, for Dorner, is the use of museums of art history? For him, the aim of any art historical museum is to show the development of art and the influence of past cultures on the modern era — something, which will not end in our time, but will continue to evolve based on premises as yet unknown. Although he remained completely eurocentric, Dorner was committed to an ideal of the autonomous value of every culture and self-conscious awareness of history in the wider political and social context (as part of culture studies).

His theoretical views were made concrete in the atmosphere rooms that he famously created at the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover and the RISD Museum in Providence. In Dorner’s own description: “a succession of what I would like to call ‘atmosphere rooms’ to be created through architectural design, infusions of music, and images of historical exteriors placed over outward-facing windows” (p. 54). The visitor should be made aware that he is in a cultural institution learning about cultures that have long vanished. Color and a sense of space/mass are they key features that Dorner works with in order to create each atmosphere room (Chapter 5).

The displays in Hanover and Providence were short-lived and until now had been considered quite marginal to Western 20th century museology. Publication of this new book on Dorner is an excellent opportunity for English-speaking scholars to learn about his innovative and original ideas. The collection contributes to an ever-growing literature on alternatives in the interwar years to the type of modernism, which treats the museum as a “white box”, formalist space. It also enriches scholarship on German art theory regarding space, mass and culture, already handled in such classic works as the collection edited by Harry Mallgrave on architectural history, Frank Mitchell’s work on art history and Kathleen Curran’s study of museum history, to name but a few.

German Art History and Scientific Thought: Beyond Formalism. Edited by Mitchell Frank and Daniel Adler. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012;art history / review /

Kathleen Curran. The Invention of the American Art Museum. From Craft to Kulturgeschichte, 1870 — 1930. Getty Trust Publications, 2016.